디멘의 블로그

Dimen's Blog

이데아를 여행하는 히치하이커

Alice in Logicland

What is a Theory of Truth?

12 Mar 2025This post was originally written in Korean, and has been machine translated into English. It may contain minor errors or unnatural expressions. Proofreading will be done in the near future.

This article is a summary of Scott Soames, What is a Theory of Truth? (1984).

Abstract

Field argued through modal objections that Tarski’s definition of truth fails to elucidate the meaning of truth. In response, Field proposed a project to define truth from causal theory. However, this paper argues that Field’s project also fails because it faces the same modal objections. Instead, the author proposes a redefinition of language that enables Tarski’s definition of truth to elucidate what truth is for each language.

1. What Does Tarski’s Theory Attempt?

Three Purposes of Theories of Truth

The philosophical significance of Tarski’s theory of truth, unlike its indubitable mathematical significance, has been the subject of ongoing debate. One reason for the continuing controversy is that scholars disagree about what the purpose of a theory of truth should be. The main positions are as follows:

- To explain what ‘truth’ means.

- To reduce ‘truth’ to other predicates and logical relations.

- To accept ‘truth’ as a primitive concept and develop philosophical positions from it.

A theory attempting 1 must consider cases where the truth predicate applies to propositions rather than sentences, such as ‘Church’s theorem is true’ or ‘John 1:14 is true’. Since Tarski’s theory of truth applies only to formal sentences, it does not correspond to 1.

Moreover, his theory does not correspond to 3 either. Tarski expressed his position that his theory of truth is completely unrelated to epistemology as follows:

The semantic definition of truth does not impose any constraints on the conditions under which the sentence “snow is white” is accepted. It only imposes the constraint that when accepting or rejecting the sentence “snow is white”, one must likewise accept or reject “‘snow is white’ is true”. Therefore, we can accept the semantic definition of truth without any modification to existing epistemological attitudes. We can remain naive realists, or remain critical realists, idealists, empiricists, or metaphysicians.

Semantic Ascent

Nevertheless, Tarski’s truth predicate can assist in the articulation of philosophical positions through what Quine called semantic ascent. For example, suppose we wish to generalise inferences of the following form:

- Snow is white $\to$ (The sky is blue $\to$ Snow is white)

- The Earth rotates $\to$ (The sun is cold $\to$ The Earth rotates)

- …

The natural generalisation is as follows:

- For any sentences $p, q$: ($p$ is true $\to$ ($q$ is true $\to$ $p$ is true))

In this formalisation, the truth predicate is indispensable for generalising each enumerated case. One might object that the dependence on the truth predicate can be eliminated as follows:

- For any sentences $p, q$: $p \to (q \to p)$

However, the above sentence is not syntactically correct. Unless we rely on second-order logic, which is fraught with philosophical problems, $p, q$ must be sentences rather than propositions. The sentences here are sentences in the mathematical logical sense, i.e., not propositions without free variables, but sentences in the philosophical sense, i.e., strings of symbols. To use the language of mathematical logic precisely, $p, q$ are Gödel numbers of sentences. In short, it is 2 rather than 1.

- $p =$ Snow is white, $q = $ The sky is blue

- $p =$ “Snow is white”, $q = $ “The sky is blue”

However, since $\to$ is a logical operator, propositions rather than sentences must appear on both sides(in the language of mathematical logic, sentences rather than Gödel numbers must appear). Therefore, $p$ must be made into the proposition $p$ is true. Formally, this is written as follows:

- $\forall p, q \in \mathbb{N} \;\; T(\ulcorner p \;\dot{\to}\; (q \;\dot{\to}\; p) \urcorner)$

Thanks to such semantic ascent, several philosophical positions can be articulated. For example, realism can be formulated as follows:

There exists some sentence $s$ such that $s$ is true, but it is impossible for human cognition to find sufficient grounds for $s$.

Because the truth predicate frequently appears in the articulation of philosophical positions, some philosophers believed that ‘truth’ is a philosophically profound concept. However, as Tarski and Quine already pointed out, this is merely for expressive convenience, and the definition of truth itself is unrelated to other philosophical positions.

Physicalism and Reduction

Tarski’s theory of truth corresponds to 2, and his philosophical background played a role here. Tarski was a moderate physicalist. The meaning of ‘moderate’ is that he understood the terminus of reduction to include not only physics but also logic and set theory. He wanted a definition of truth compatible with his physicalism, and therefore rejected the approach of accepting truth as a primitive concept and listing axioms about its characteristics. Instead, he reduced truth to set theory by inductively defining a certain set, then showing both ① that a predicate having that set as its truth set entails all T-schemas, and ② that the set satisfying that inductive definition is unique.

In modern times, Tarski’s theory of truth has become the subject of philosophical criticism. The author of this paper argues that this is unjust criticism. The main thrust of the criticism is that his theory lacks the conditions that a theory of truth should properly possess, but these conditions are in fact unjust or incoherent.

2. Field’s Criticism

Two Stages of Tarskian Definition

Field distinguishes Tarski’s definition of truth into two stages. The first is primitive denotation. In this stage, one defines what it means for a name $n$ to denote an object $o$ in language $L$, and for a predicate $P$ to hold of an object $o$. This definition consists of the following:

- Name $n$ denotes object $o$ in $L$ $\iff$ one of the following holds:

- $n = \text{‘apple’}, o = $ apple

- $n = \text{‘banana’}, o = $ banana

- $n = \text{‘coconut’}, o = $ coconut

- …

- Predicate $P$ holds of object $o$ in $L$ $\iff$ one of the following holds:

- $P = \text{‘Round’}, o = $ apple, coconut, …

- $P = \text{‘Long’}, o = $ banana, …

- …

The second stage is the recursive definition of truth. This definition is as follows:

- Sentence $S$ is true in $L$ $\iff$ $S \in K$

where $K$ is the unique set satisfying the following:

- When there exists an object $o$ such that $n$ denotes $o$ and $P$ holds of $o$, then $\ulcorner Pn \urcorner \in K$

- When $A \in K$ or $B \in K$, then $\ulcorner A \lor B \urcorner \in K$

- When $A \notin K$, then $\ulcorner \lnot A \urcorner \in K$

Modal Objections and Field’s Project

Field argues that primitive denotation fails to elucidate the meaning of ‘$n$ denotes $o$’. According to Field, the denotation relation depends on the psychology of language users. Therefore, it was possible for ‘apple’ to denote banana rather than apple. However, in Tarski’s primitive denotation, since ‘apple’ is coupled with apple within the necessary and sufficient condition for $n$ to denote $o$, it is necessary that ‘apple’ denotes apple. In short, the problem is that the definition of denotation is hardcoded.

Therefore, Field seeks to overcome Tarski’s limitations by presenting a physicalist reduction of denotation. Field’s project is to present a physico-causal theory of denotation based on Kripke’s theory, thereby providing a theory that derives the correct definition of truth for any speaker’s language $L$.

Problems with Field’s Project

However, Field’s project has problems. The first problem is the issue raised by the denotation of abstract objects that appear to lack causal efficacy.

However, a more serious second problem is that, following Field’s objection, not only does primitive denotation fail to elucidate the meaning of denotation, but the recursive definition of truth also fails to elucidate the meaning of truth. This is because rules related to logical operators are hardcoded in the recursive definition of truth. Therefore, the modal objection is equally valid. For instance, while it is clearly contingent that $\lor$ means disjunction, according to the recursive definition, “$T(\ulcorner A \lor B \urcorner) \Leftrightarrow T(\ulcorner A \urcorner)$ or $T(\ulcorner B \urcorner)$” is necessary.

Therefore, Field must also present physicalist reductions of 3, 4, 5, … as well as 1 and 2.

- Name $n$ denotes object $o$.

- Predicate $P$ holds of object $o$.

- Sentence $A$ is the negation of sentence $B$.

- Sentence $A$ is the disjunction of sentences $B, C$.

- Sentence $A$ existentially quantifies variable $u$ in sentence $B$. (…)

However, it is unclear how 3, 4, 5, … can be reduced without circular dependence on truth. The author argues that attempts at this work so far have not been successful. As an example, he mentions Quine’s attempt to reduce truth-functional operators to collective acceptance or rejection by the linguistic community, which is problematic for reasons given in Alan Berger, Quine on ‘Alternative Logics’ and Verdict Tables (1980). (I haven’t read this yet, but it’s probably a modal problem.)

Addition. Burgess points out in Truth that Field’s project’s dependence on Kripke’s theory is also problematic. This is because Kripke’s theory is not a theory of reference. Kripke’s theory is about how the initial act of using name $n$ to refer to object $o$ continues to form the semantics of names; in his theory, reference is a primitive concept. Kripke himself strongly objected to the popular opinion that his theory is reductionist about reference.

3. The Relationship Between Meaning and Truth

Most philosophers of language acknowledge that meaning and truth are in a mutually suggestive relationship. For instance, they acknowledge the following:

- If sentence $S$ means $p$ in language $L$, then the necessary and sufficient condition for $S$ to be true in $L$ is $p$.

Therefore, some philosophers expected that Tarski’s theory of truth could be extended to a theory of meaning. However, the modal objection also shows that Tarski’s theory of truth cannot be connected to a theory of meaning. For example, Tarski’s truth predicate defined for Peano arithmetic suggests 1 but not 2. Rather, Tarski’s definition suggests 3.

- $T(\ulcorner 1 \;\dot{+}\; 1 = 2 \urcorner) \Leftrightarrow 1 + 1 = 2$

- If the meaning of $\dot{+}$ were multiplication, then $T(\ulcorner 1 \;\dot{+}\; 1 = 2 \urcorner) \Leftrightarrow 1 \times 1 = 2$

- If the meaning of $\dot{+}$ were multiplication, then $T(\ulcorner 1 \;\dot{+}\; 1 = 2 \urcorner) \Leftrightarrow 1 + 1 = 2$

Of course, since Tarski requires that the definition of truth be materially adequate, he would argue that if the meaning of $\dot{+}$ were actually multiplication, then $T$ suggesting $T(\ulcorner 1 \;\dot{+}\; 1 = 2 \urcorner) \Leftrightarrow 1 + 1 = 2$ would not be a correct definition of truth. That is, Tarski claims the following: ($\square p$ means that $p$ is necessary.)

a. $\square($ $T$ is a truth predicate $\to$ ( sentence $S$ means $\phi$ $\to$ $\;T(S) \Leftrightarrow \phi$ ) $)$

However, the approach of deriving a theory of meaning from a theory of truth depends on the following proposition:

b. $T$ is a truth predicate $\to$ $\square($ sentence $S$ means $\phi$ $\to$ $\;T(S) \Leftrightarrow \phi$ $)$

a and b are different propositions. Tarski’s theory guarantees a but not b.

4. Newly Defining ‘Theory of Truth’

Meaning as an Essential Property of Language

The criticism of Tarski’s definition of truth examined so far presupposes that the objects denoted by names in language $L$ must be contingent, i.e., that semantics is dependent on the speakers of $L$. However, instead of viewing language in this way, the author proposes to view information about what names denote as also part of the language.

For instance, in first-order logic, language $L$ can be regarded as a triple $\langle S_L, D_L, F_L \rangle$(the language spoken of here is quite different from the language of model theory. The language here has not only syntax but also semantics). The meaning of each is as follows:

- $S_L$: The set of well-formed formulae

- $D_L$: The set of denotable objects

- $F_L$: An interpretation function that maps each name to an object

When language is defined in this way, Tarski’s definition of truth produces a materially adequate truth predicate $T_L$ for any language $L$. Moreover, since $F_L$ is merely a set of tuples, it does not depart from Tarski’s physicalist line. In short, the author argues that by regarding the semantics of a language as an essential property of that language, Tarski’s definition of truth can be elevated to a general definition of truth. Therefore, there is no case where name $n$ in language $L$ denoted an object other than the object $o$ it denotes. The community of language users is not the agent that gives semantics to language, but the agent that chooses which language to use. And the problem of determining the language used by a community is a matter of pragmatics, not semantics.

Type and Token

Field’s physicalist background led him to focus on utterances rather than sentences. Field argues that Tarski only provided a definition of truth for sentences, but failed to provide a definition of truth for utterances. If Tarski had heard this objection, he would have said that this work should be divided into two stages as follows:

- Through what principle does utterance $u$ in language $L$ become an utterance of sentence $s$?

- What does it mean for sentence $s$ to be true in language $L$?

Therefore, Tarski’s definition is a type definition. In contrast, Field seeks to answer the following question:

- What does it mean for token $t$ to be true in language $L$?

Here, a token might be graphite marks on paper, chalk marks on a blackboard, or speech sounds. That is, what Field seeks is a token definition. However, it is questionable whether a token definition of truth is possible. Field himself attempted to reach a token definition by modifying Tarski’s definition as follows:

- A token of $\ulcorner \lnot e \urcorner$ is true $\Leftrightarrow$ the token of $e$ contained in that token is not true.

However, as mentioned earlier, the above definition hardcodes the meaning of $\lnot$ as negation, so it faces the same modal objection. Therefore, the above definition should be modified as follows:

- A token of proposition $A$ that is the negation of proposition $B$ is true $\Leftrightarrow$ some token of $B$ is false

But even if ‘…is the negation of’ can be reduced physicalistically, it is unclear how to specify the relevant token of $B$ in a given context. For example, consider the following sentence:

Trump’s claim about climate crisis is wrong.

It is unclear which of the numerous utterance tokens Trump has made regarding climate crisis should be the object of negation in the above sentence. The token of $B$ might not even exist. For example, consider the following sentence:

If Trump were to give a lecture on ethics, most of the content would be wrong.

To my knowledge, Trump has never given a lecture on ethics, so the token that is the object of negation in the above sentence does not exist. However, it seems perfectly reasonable to claim that the above sentence is true. This reveals the difficulties faced by a token definition of truth. From this, the author argues that we should accept Tarski’s type definition of truth for now, and regard whether the pragmatic relationship between language, expression, speaker, and utterance can be reduced to physicalism as a separate issue.

The Problem of Pragmatics

Although the author has attributed the relationship between language and speaker to the realm of pragmatics, this does not mean that this problem is unimportant. This is because there are various philosophical considerations regarding the relationship between language and speaker. For instance, Quine argues that the statement “speaker $A$ uses language $L$” cannot be reduced physicalistically(the gavagai argument). According to the author, Quine’s position can be seen as accepting Tarski’s definition of truth while rejecting the physicalist reduction of the relationship between language and speaker.

The Problem of Truth-Conditional Semantics

Finally, the author argues that attempts to derive a theory of meaning from the concept of truth, particularly theories that the acquisition of the concept of truth is a prerequisite for semantic competence, cannot all succeed. Although not explained in detail, it is probably the following problem. Attempts to derive a theory of meaning from the concept of

하지만 $\leftrightarrow$를 고전 논리의 동치 관계로 이해하든, 양상 논리의 필연적 동치 관계로 이해하든 간에 2는 성립하지 않는다. 예를 들어 다음은 필연적으로 성립한다.

- $1 + 1 = 2 \leftrightarrow $ 페르마의 마지막 정리

그러나 $1 + 1 = 2$의 의미가 페르마의 마지막 정리인 것은 아니다.

5. 결론

결론적으로 논문의 저자는 참에 대한 이론이 의미에 대한 이론과 직결되어 있어야 한다는 요구는 부당하다고 주장함으로써 타르스키의 참 정의와, 그것이 함의하는 참에 대한 축소주의deflationism를 옹호한다. 이것이 참에 대한 이론이 불필요함을 의미하지는 않는다. 크립키의 참 이론은 타르스키의 참 이론을 실질적으로 발전시켰다. 그러나 그 발전은 이미 우리에게 익숙한 참의 성질들을 T-스키마로써 정확히 해명하고, 올바르게 설계된 형태론으로 거짓말쟁이 역설과 같은 모순을 회피하는 데 있다. 참에 대한 이론으로부터 이 이상을 기대하는 것은 바람직하지 않다.

시제 논리

10 Mar 2025도입

다음의 세 문장을 보자.

- 가영이는 언젠가 등교할 것이다.

- 나영이는 언젠가 등교할 것이다.

- 나영이는 가영이가 등교하기 전에 등교하지 않는다.

위로부터 다음을 추론할 수 있다.

4. 가영이가 먼저 등교하고 나영이가 등교할 것이다.

그러나 고전 논리는 — 적어도 표면적으로는 — 위의 추론 관계를 함의하지 않는다. 따라서 우리에게 필요한 것은 시간에 대해 추론할 수 있는 논리학, 즉 시제 논리temporal logic이다.

1. 고전적 시제 논리

1.1. 의미론

시제 논리를 정의하는 길은 두 가지가 있다. 첫째는 고전 논리에 특정 구조를 부과함으로써 시제 논리를 얻는 것이다. 이 방법을 먼저 알아보자.

시제 논리의 부호수signature는 하나의 이항 관계 $\prec$와, 0개 이상의 일항 술어 $P, Q, \dots$로 이루어져 있다. 시제 논리의 모델은 다음과 같다. (이 모델을 크립키Kripke 모델이라고 한다)

\[\mathcal{T} = (T, \prec^\mathcal{T}, P^\mathcal{T}, Q^\mathcal{T}, \dots)\]- 전체universe $T$: 상정하는 모든 순간을 의미한다.

- $t_1 \prec^\mathcal{T} t_2$: $t_1$이 $t_2$보다 과거라는 의미이다.

- $P^\mathcal{T}(t)$: $P$가 시점 $t$에서 참이라는 의미이다.

예를 들어 어제, 오늘, 그리고 내일만을 고려하는 시제 논리의 경우 $T = \lbrace -1, 0, 1 \rbrace $로 둘 수 있다. 고전 역학은 $T = \mathbb{R}$을 간주한다.

가영이가 등교하는 사건을 $A$, 나영이가 등교하는 사건을 $B$라고 하면 도입의 3은 다음과 같이 쓸 수 있다.

\[\forall t_1 \forall t_2 \; \big( A(t_1) \land B(t_2) \rightarrow t_1 \prec t_2 \big)\]$\phi$가 하나의 자유변수 $x$를 가지는 문장이라고 하자. $t \in T$를 현재로 뒀을 때 $\phi$가 참이라는 것을, $\mathcal{T} \vDash \phi[t]$와 같이 적는다.

1.2. 프레임

집합과, 그 위에 정의된 이항 관계의 쌍 $(T, \prec)$를 프레임frame이라고 부른다. $\mathbf{F}$가 프레임의 모임class이라고 하자. $(T, \prec) \in \mathbf{F}$인 임의의 모델 $\mathcal{T} = (T, \prec, \lbrace P^\mathcal{T} \rbrace )$와 임의의 $t \in T$에 대해 $\mathcal{T} \vDash \phi[t]$일 때, $\phi$가 $\mathbf{F}$에 대해 참이라고 한다.

$\mathbf{F}$가 특정 성질을 가질 것을 요구함으로써 시간의 특징을 포착할 수 있다. 다음과 같은 성질을 요구할 수 있다.

- 추이성transitivity: 임의의 서로 다른 $t_1, t_2, t_3 \in T$에 대해 $t_1 \prec t_2, t_2 \prec t_3$라면 $t_1 \prec t_3$이다.

- 선형성linearity: 임의의 서로 다른 $t_1, t_2 \in T$에 대해 $t_1 \prec t_2$이거나 $t_2 \prec t_1$이다.

- 조밀성denseness: 임의의 서로 다른 $t_1, t_2 \in T$에 대해 어떤 $t_3 \in T$가 존재하여 $t_1 \prec t_3 \prec t_2$이다.

- 우 연장성R-extendability: 임의의 $t \in T$에 대해 어떤 $t’ \in T$가 존재하여 $t \prec t’$이다.

- 좌 연장성L-extendability: 임의의 $t \in T$에 대해 어떤 $t’ \in T$가 존재하여 $t’ \prec t$이다.

도입의 논증은 선형 프레임에 대해 참임을 보일 수 있다.

2. 독립적 시제 논리

시제 논리를 정의하는 두 번째 방식은 시제 논리에 특수한 논리 기호를 도입하는 것이다. 각각 다음과 같이 읽는다.

- $\mathsf{F}p$: 언젠가 $p$일 것이다Future p

- $\mathsf{P}p$: 언젠가 $p$였다Past p

- $\mathsf{G}p$: 언제나 $p$일 것이다Going to always be p

- $\mathsf{H}p$: 언제나 $p$였다Has always been p

$\mathsf{F}, \mathsf{P}, \mathsf{G}, \mathsf{H}$의 관계는 다음과 같다.

- $\mathsf{F}p \equiv \lnot\mathsf{G}\lnot p$

- $\mathsf{P}p \equiv \lnot\mathsf{H}\lnot p$

독립적 시제 논리의 명제는 메레디스 번역Meredith translation을 통해 언제나 고전적 시제 논리의 명제로 변환할 수 있다. 예를 들어 $\mathsf{G}p$는 $\forall x \succ t \; p(x)$로 번역된다. 그러나 역은 성립하지 않는다. 따라서 독립적 시제 논리는 고전적 시제 논리보다 표현력이 약하다. 그럼에도 독립적 시제 논리가 연구할 만한 주제인 이유는, 표현력을 일부 포기하는대가로 결정 가능성, 완전성 등의 좋은 성질을 얻을 수 있을 뿐더러, 양상 논리와의 연결 고리를 제공하는 등 철학적 의의 또한 크기 때문이다.

독립적 시제 논리의 모델은 종속적 시제 논리와 마찬가지로 $\mathcal{T} = (T, \prec, \lbrace P^\mathcal{T} \rbrace )$이다. 만족 관계는 자연스럽게 정의한다. 예를 들어,

- $\mathcal{T} \vDash \mathsf{F}p[t] \iff$ 어떤 $t \prec t’$에 대해, $\mathcal{T} \vDash p[t’]$

3. 시제 공리

지금까지 시제 논리의 의미론을 살펴 보았다. 이제 시제 논리의 증명을 살펴본다.

3.1. 최소 시제 논리

최소 시제 논리 $L_0$는 다음의 공리로 이루어져 있다.

- $\tau$가 명제 논리의 항진명제일 때, $\tau$

- $\mathsf{G}(\phi \to \psi) \to (\mathsf{G}\phi \to \mathsf{G}\psi)$

- $\mathsf{H}(\phi \to \psi) \to (\mathsf{H}\phi \to \mathsf{H}\psi)$

- $\phi \to \mathsf{GP}\phi$

- $\phi \to \mathsf{HF}\phi$

그리고 다음의 추론 규칙으로 이루어져 있다.

- MP $\vdash \phi, \phi \to \psi \implies \vdash \psi$

- TG1: $\vdash \phi \implies \vdash \mathsf{G}\phi$

- TG2: $\vdash \phi \implies \vdash \mathsf{H}\phi$

MP는 Modus Ponens, TG는 Temporal Generalisation의 약어이다.

TG가 $\vdash \phi \to \mathsf{G}\phi$를 의미하지 않는다는 사실에 유의하라. TG는 논리적으로 증명된 명제 $\phi$에 한해, $\mathsf{G}\phi$ 또는 $\mathsf{H}\phi$를 도출할 수 있다는 의미이다. 즉, TG는 논리적 명제가 시간과 무관하다는 의미이다.

정리. $L_0$는 건전하다.

증명. 명제 논리의 건전성 정리와 거의 동일하게, 논리식의 형태에 대한 귀납법으로 증명한다.

정리. $L_0$에서 증명 가능성은 다음 규칙에 대해 닫혀 있다.

- 거울 규칙mirror rule: 명제 $\phi$에 등장하는 $\mathsf{G}$와 $\mathsf{H}$, $\mathsf{F}$와 $\mathsf{P}$를 서로 바꾼 명제를 거울 명제 $\bar{\phi}$라고 하자. $\vdash \phi$라면 $\vdash \bar{\phi}$이다.

- 베커 규칙Becker’s rule: $\mathsf{T}$가 $\mathsf{G, H, F, P}$ 중 하나라고 하자. $\vdash \phi \to \psi$라면 $\vdash \mathsf{T}\phi \to \mathsf{T}\psi$이다.

- 쌍대 규칙dual rule: 명제 $\phi$에 등장하는 $\land$와 $\lor$, $\mathsf{G}$와 $\mathsf{F}$, $\mathsf{H}$와 $\mathsf{P}$를 서로 바꾼 명제를 쌍대 명제 $\phi^\ast$라고 하자. $\vdash \phi$라면 $\vdash \phi^\ast$이다.

증명. 연습문제 (^^)

정리. $L_0$는 모든 프레임의 모임 $\mathbf{F}_0$에 대해 완전하다.

증명. TODO

3.2. 고전역학의 시제 논리

추이성, 선형성, 조밀성, 좌우 연장성을 가지는 프레임들의 모임 $\mathbf{F}_1$을 고려하자. $\mathbf{F}_1$은 고전역학에서 상정하는 시간이다. $\mathbf{F}_1$에서 건전하고 완전한 공리계를 찾아 보자.

고전역학의 시제 논리 $L_1$은 $L_0$에 다음 공리를 추가한 것이다.

- $\mathsf{G} p \to \mathsf{GG}p$ (추이성)

- $(\mathsf{P}p \land \mathsf{P}q) \to (\mathsf{P}(p \land \mathsf{P}q) \lor \mathsf{P}(p \land q) \lor \mathsf{P}(\mathsf{P}p \land q))$ (좌 선형성)

- $(\mathsf{F}p \land \mathsf{F}q) \to (\mathsf{F}(p \land \mathsf{F}q) \lor \mathsf{F}(p \land q) \lor \mathsf{F}(\mathsf{F}p \land q))$ (우 선형성)

- $\mathsf{H}p \to \mathsf{P}p$ (좌 연장성)

- $\mathsf{G}p \to \mathsf{F}p$ (우 연장성)

- $\mathsf{GG}p \to \mathsf{G}p$ (조밀성)

햄린Hamblin의 정리. $L_1$에서 시제 기호의 조합은 14가지 시제 중 하나와 동치이다. 14가지 시제는 $\mathsf{FH, H, PH, HP, P, GP}$와 $\mathsf{PG, G, FG, GF, F, HF}$, 그리고 $\mathsf{GH} = \mathsf{HG}$와 $\mathsf{FP} = \mathsf{PF}$이다.

증명. 추이적 프레임에서 $\mathsf{PP}$와 같이 중첩된 시제는 단일 시제 $\mathsf{P}$와 동치임을 쉽게 보일 수 있다. 따라서 $\mathsf{X} \neq \mathsf{Y}$, $\mathsf{Y} \neq \mathsf{Z}$인 시제들의 조합 $\mathsf{XYZ}$은 어떤 두 시제 조합과 동치임을 보이면 된다. 거울 규칙과 쌍대 규칙에 의해 $\mathsf{Z} = \mathsf{G}$인 경우만 고려하면 된다. 한편 $\mathsf{XY}$와 $\mathsf{X’Y’}$가 서로 동치가 아니라는 것을 보이기 위해서는 함의 관계가 성립하지 않는 크립키 모델을 찾으면 된다.

정리. $L_1$은 $\mathbf{F}_1$에 대해 완전하다.

4. 시제 술어 논리

고전 논리학에서 술어 논리는 명제 논리에 다음 공리를 추가한 것이다.

- $\forall x \phi \to \phi[y/x]$ (단, $y$는 $\phi$에서 $x$에 대해 자유)

- $\forall x (\phi \to \psi) \to (\phi \to \forall x \psi)$ (단, $x$는 $\phi$의 자유변수가 아님)

- $x = x$

- $x = y \to (\phi[x/z] \to \phi[y / z]$) (단, $x, y$는 $\phi$에서 $z$에 대해 자유)

그리고 다음의 추론 규칙을 추가한다.

- UGUniversal Generalisation: $\vdash \phi \implies \vdash \forall x \phi$

시제 논리 $L_0$에 상술한 공리들과 추론 규칙을 추가한 논리 체계를 시제 술어 논리 $L_P$라고 하자.

정리. $L_P$는 다음을 증명한다.

- 정 바르칸direct Barcan: $\forall x \mathsf{G}\phi \to \mathsf{G}\forall x \phi$

- 역 바르칸converse Barcan: $\mathsf{G}\forall x \phi \to \forall x \mathsf{G} \phi$

- 동일성의 영속성permanence of identity: $x = y \to \mathsf{G}(x = y)$

증명. 역 바르칸 명제만 증명해 보자.

\[\begin{aligned} &1. &&\forall x \phi \to \phi &&&\text{Axiom} \\ &2. &&\mathsf{G}\forall x \phi \to \mathsf{G} \phi &&&\text{Becker}\\ &3. &&\forall x (\mathsf{G}\forall x \phi \to \mathsf{G}\phi) &&&\text{2, UG}\\ &4. &&\forall x (\mathsf{G}\forall x \phi \to \mathsf{G}\phi) \to (\mathsf{G}\forall x \phi \to \forall x \mathsf{G}\phi) &&&\text{Axiom}\\ &5. &&\mathsf{G}\forall x \phi \to \forall x \mathsf{G} \phi \quad &&&\text{3, 4, MP} \\ & \blacksquare \end{aligned}\]자연 언어로 풀어 쓰자면,

- 정 바르칸: 현재 존재하는 모든 대상이 언제나 ____라고 하자. 그러면 임의의 미래 시점에 대해, 그때 존재하는 모든 대상은 ____이다.

- 역 바르칸: 임의의 미래 시점에서 대해, 그때 존재하는 모든 대상은 ____라고 하자. 그러면 현재 존재하는 모든 대상이 언제나 ____이다.

- 동일성의 영속성: 동일한 두 대상은 언제나 동일하다.

동일성의 영속성은 시제 논리에서 상수가 고정 지시어rigid designator처럼 행동한다고 직관적으로 올바르다. 그러나 바르칸 명제는 직관적으로 틀렸다. 일례로 $\phi(x)$를 “$x$가 존재한다”로 치환해 보자.

- 역 바르칸: ① 임의의 미래 시점에서 대해, 그때 존재하는 모든 대상은 존재한다고 하자. ② 그러면 현재 존재하는 모든 대상이 언제나 존재한다.

하지만 이 명제는 틀렸다. ①은 자명하게 성립하지만, 현재 존재하는 모든 대상이 영원히 존재할 것은 아니므로 ②는 성립하지 않기 때문이다. 따라서 역 바르칸 명제는 문제적이다.

$L_P$가 바르칸 명제 같은 병리적 명제를 도출하는 이유는 TG가 열린 명제에 대해 유효하지 않기 때문이다(TG는 베커 규칙의 증명에 필요하다. 즉, 증명의 문제는 2단계에 있다). 앞서 말했듯이 TG는 논리적으로 참인 명제는 시간에 상관 없이 참이라는 의미이다. 그러나 열린 명제는 참도 아니고 거짓도 아니다. 열린 명제는 특정 대상에 의해 만족되거나, 만족되지 않기 때문이다.

이 문제를 극복하기 위해 TG를 닫힌 명제에 대해서만 적용 가능하도록 제안하는 방안을 강구할 수 있으나, 제한된 시제 술어 논리는 일부 바람직한 명제를 증명하지 못함이 알려져 있다. 건전하면서도 완전한 시제 술어 논리를 만드는 작업은 아직도 해결되지 않은 문제이다.

Temporal Logic

10 Mar 2025This post was originally written in Korean, and has been machine translated into English. It may contain minor errors or unnatural expressions. Proofreading will be done in the near future.

Introduction

Consider the following three statements.

- Gayeong will go to school at some point.

- Nayeong will go to school at some point.

- Nayeong will not go to school before Gayeong goes to school.

From these, we can infer the following.

4. Gayeong will go to school first, and then Nayeong will go to school.

However, classical logic—at least superficially—does not entail the above inference relation. Therefore, what we need is a logic that can reason about time, namely temporal logic.

1. Classical Temporal Logic

1.1. Semantics

There are two ways to define temporal logic. The first is to obtain temporal logic by imposing a particular structure on classical logic. Let us examine this method first.

The signature of temporal logic consists of one binary relation $\prec$ and zero or more unary predicates $P, Q, \dots$. A model of temporal logic is as follows. (This model is called a Kripke model.)

\[\mathcal{T} = (T, \prec^\mathcal{T}, P^\mathcal{T}, Q^\mathcal{T}, \dots)\]- Universe $T$: represents all the moments under consideration.

- $t_1 \prec^\mathcal{T} t_2$: means that $t_1$ is earlier than $t_2$.

- $P^\mathcal{T}(t)$: means that $P$ is true at time $t$.

For example, in temporal logic considering only yesterday, today, and tomorrow, we can set $T = \lbrace -1, 0, 1 \rbrace $. Classical mechanics considers $T = \mathbb{R}$.

If we let $A$ denote the event of Gayeong going to school and $B$ denote the event of Nayeong going to school, then statement 3 from the introduction can be written as follows.

\[\forall t_1 \forall t_2 \; \big( A(t_1) \land B(t_2) \rightarrow t_1 \prec t_2 \big)\]Let $\phi$ be a formula with one free variable $x$. When $\phi$ is true with $t \in T$ taken as the present, we write this as $\mathcal{T} \vDash \phi[t]$.

1.2. Frames

A pair $(T, \prec)$ consisting of a set and a binary relation defined on it is called a frame. Let $\mathbf{F}$ be a class of frames. When $\mathcal{T} \vDash \phi[t]$ for any model $\mathcal{T} = (T, \prec, \lbrace P^\mathcal{T} \rbrace )$ with $(T, \prec) \in \mathbf{F}$ and any $t \in T$, we say that $\phi$ is true with respect to $\mathbf{F}$.

By requiring $\mathbf{F}$ to have certain properties, we can capture characteristics of time. The following properties can be required:

- Transitivity: for any distinct $t_1, t_2, t_3 \in T$, if $t_1 \prec t_2$ and $t_2 \prec t_3$, then $t_1 \prec t_3$.

- Linearity: for any distinct $t_1, t_2 \in T$, either $t_1 \prec t_2$ or $t_2 \prec t_1$.

- Density: for any distinct $t_1, t_2 \in T$, there exists some $t_3 \in T$ such that $t_1 \prec t_3 \prec t_2$.

- Right-extendability: for any $t \in T$, there exists some $t’ \in T$ such that $t \prec t’$.

- Left-extendability: for any $t \in T$, there exists some $t’ \in T$ such that $t’ \prec t$.

The argument from the introduction can be shown to be valid with respect to linear frames.

2. Independent Temporal Logic

The second way to define temporal logic is to introduce logical symbols specific to temporal logic. Each is read as follows:

- $\mathsf{F}p$: Future $p$ (at some point $p$ will be the case)

- $\mathsf{P}p$: Past $p$ (at some point $p$ was the case)

- $\mathsf{G}p$: Going to always be $p$ (always $p$ will be the case)

- $\mathsf{H}p$: Has always been $p$ (always $p$ was the case)

The relationships between $\mathsf{F}, \mathsf{P}, \mathsf{G}, \mathsf{H}$ are as follows:

- $\mathsf{F}p \equiv \lnot\mathsf{G}\lnot p$

- $\mathsf{P}p \equiv \lnot\mathsf{H}\lnot p$

Propositions of independent temporal logic can always be translated into propositions of classical temporal logic through the Meredith translation. For example, $\mathsf{G}p$ is translated as $\forall x \succ t \; p(x)$. However, the converse does not hold. Therefore, independent temporal logic has weaker expressive power than classical temporal logic. Nevertheless, independent temporal logic is a subject worth studying because, in exchange for sacrificing some expressive power, one can obtain good properties such as decidability and completeness, and it also provides connections to modal logic, amongst other significant philosophical merits.

The model of independent temporal logic is $\mathcal{T} = (T, \prec, \lbrace P^\mathcal{T} \rbrace )$, the same as dependent temporal logic. The satisfaction relation is defined naturally. For example,

- $\mathcal{T} \vDash \mathsf{F}p[t] \iff$ for some $t \prec t’$, $\mathcal{T} \vDash p[t’]$

3. Temporal Axioms

So far we have examined the semantics of temporal logic. Now let us examine proofs in temporal logic.

3.1. Minimal Temporal Logic

The minimal temporal logic $L_0$ consists of the following axioms:

- When $\tau$ is a tautology of propositional logic, $\tau$

- $\mathsf{G}(\phi \to \psi) \to (\mathsf{G}\phi \to \mathsf{G}\psi)$

- $\mathsf{H}(\phi \to \psi) \to (\mathsf{H}\phi \to \mathsf{H}\psi)$

- $\phi \to \mathsf{GP}\phi$

- $\phi \to \mathsf{HF}\phi$

And it consists of the following inference rules:

- MP $\vdash \phi, \phi \to \psi \implies \vdash \psi$

- TG1: $\vdash \phi \implies \vdash \mathsf{G}\phi$

- TG2: $\vdash \phi \implies \vdash \mathsf{H}\phi$

MP is an abbreviation for Modus Ponens, and TG is an abbreviation for Temporal Generalisation.

Note that TG does not mean $\vdash \phi \to \mathsf{G}\phi$. TG means that only for logically proven propositions $\phi$, one can derive $\mathsf{G}\phi$ or $\mathsf{H}\phi$. That is, TG means that logical propositions are independent of time.

Theorem. $L_0$ is sound.

Proof. The proof is by induction on the form of logical formulae, almost identical to the soundness theorem for propositional logic.

Theorem. Provability in $L_0$ is closed under the following rules:

- Mirror rule: Let the mirror proposition $\bar{\phi}$ be the proposition obtained by swapping $\mathsf{G}$ with $\mathsf{H}$ and $\mathsf{F}$ with $\mathsf{P}$ in proposition $\phi$. If $\vdash \phi$, then $\vdash \bar{\phi}$.

- Becker’s rule: Let $\mathsf{T}$ be one of $\mathsf{G, H, F, P}$. If $\vdash \phi \to \psi$, then $\vdash \mathsf{T}\phi \to \mathsf{T}\psi$.

- Dual rule: Let the dual proposition $\phi^\ast$ be the proposition obtained by swapping $\land$ with $\lor$, $\mathsf{G}$ with $\mathsf{F}$, and $\mathsf{H}$ with $\mathsf{P}$ in proposition $\phi$. If $\vdash \phi$, then $\vdash \phi^\ast$.

Proof. Exercise (^^)

Theorem. $L_0$ is complete with respect to the class of all frames $\mathbf{F}_0$.

Proof. TODO

3.2. Temporal Logic of Classical Mechanics

Consider the class $\mathbf{F}_1$ of frames that have transitivity, linearity, density, and left and right extendability. $\mathbf{F}_1$ represents time as postulated in classical mechanics. Let us find an axiom system that is sound and complete for $\mathbf{F}_1$.

The temporal logic of classical mechanics $L_1$ is obtained by adding the following axioms to $L_0$:

- $\mathsf{G} p \to \mathsf{GG}p$ (transitivity)

- $(\mathsf{P}p \land \mathsf{P}q) \to (\mathsf{P}(p \land \mathsf{P}q) \lor \mathsf{P}(p \land q) \lor \mathsf{P}(\mathsf{P}p \land q))$ (left linearity)

- $(\mathsf{F}p \land \mathsf{F}q) \to (\mathsf{F}(p \land \mathsf{F}q) \lor \mathsf{F}(p \land q) \lor \mathsf{F}(\mathsf{F}p \land q))$ (right linearity)

- $\mathsf{H}p \to \mathsf{P}p$ (left extendability)

- $\mathsf{G}p \to \mathsf{F}p$ (right extendability)

- $\mathsf{GG}p \to \mathsf{G}p$ (density)

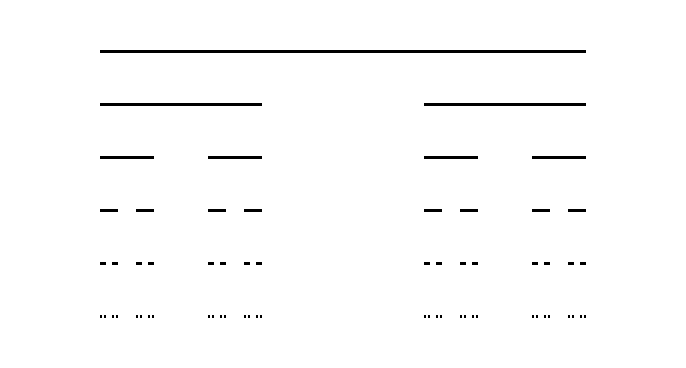

Hamblin’s theorem. In $L_1$, combinations of temporal symbols are equivalent to one of 14 tenses. The 14 tenses are $\mathsf{FH, H, PH, HP, P, GP}$ and $\mathsf{PG, G, FG, GF, F, HF}$, together with $\mathsf{GH} = \mathsf{HG}$ and $\mathsf{FP} = \mathsf{PF}$.

Proof. In transitive frames, nested tenses such as $\mathsf{PP}$ can easily be shown to be equivalent to the single tense $\mathsf{P}$. Therefore, it suffices to show that combinations $\mathsf{XYZ}$ of tenses where $\mathsf{X} \neq \mathsf{Y}$ and $\mathsf{Y} \neq \mathsf{Z}$ are equivalent to some combination of two tenses. By the mirror rule and dual rule, we need only consider the case where $\mathsf{Z} = \mathsf{G}$. Meanwhile, to show that $\mathsf{XY}$ and $\mathsf{X’Y’}$ are not equivalent to each other, one can find a Kripke model where the implication relation does not hold.

Theorem. $L_1$ is complete with respect to $\mathbf{F}_1$.

4. Temporal Predicate Logic

In classical logic, predicate logic is obtained by adding the following axioms to propositional logic:

- $\forall x \phi \to \phi[y/x]$ (provided $y$ is free for $x$ in $\phi$)

- $\forall x (\phi \to \psi) \to (\phi \to \forall x \psi)$ (provided $x$ is not a free variable of $\phi$)

- $x = x$

- $x = y \to (\phi[x/z] \to \phi[y / z]$) (provided $x, y$ are free for $z$ in $\phi$)

And the following inference rule is added:

- UG (Universal Generalisation): $\vdash \phi \implies \vdash \forall x \phi$

The logical system obtained by adding the aforementioned axioms and inference rule to temporal logic $L_0$ is called temporal predicate logic $L_P$.

Theorem. $L_P$ proves the following:

- Direct Barcan: $\forall x \mathsf{G}\phi \to \mathsf{G}\forall x \phi$

- Converse Barcan: $\mathsf{G}\forall x \phi \to \forall x \mathsf{G} \phi$

- Permanence of identity: $x = y \to \mathsf{G}(x = y)$

Proof. Let us prove only the converse Barcan formula.

\[\begin{aligned} &1. &&\forall x \phi \to \phi &&&\text{Axiom} \\ &2. &&\mathsf{G}\forall x \phi \to \mathsf{G} \phi &&&\text{Becker}\\ &3. &&\forall x (\mathsf{G}\forall x \phi \to \mathsf{G}\phi) &&&\text{2, UG}\\ &4. &&\forall x (\mathsf{G}\forall x \phi \to \mathsf{G}\phi) \to (\mathsf{G}\forall x \phi \to \forall x \mathsf{G}\phi) &&&\text{Axiom}\\ &5. &&\mathsf{G}\forall x \phi \to \forall x \mathsf{G} \phi \quad &&&\text{3, 4, MP} \\ & \blacksquare \end{aligned}\]In natural language terms:

- Direct Barcan: suppose that all objects currently existing will always be ____. Then for any future time point, all objects existing at that time will be ____.

- Converse Barcan: suppose that for any future time point, all objects existing at that time will be ____. Then all objects currently existing will always be ____.

- Permanence of identity: two identical objects are always identical.

The permanence of identity is intuitively correct, as constants behave like rigid designators in temporal logic. However, the Barcan formulae are intuitively false. As an example, let us substitute “$x$ exists” for $\phi(x)$.

- Converse Barcan: ① suppose that for any future time point, all objects existing at that time exist. ② Then all objects currently existing will always exist.

But this proposition is false. ① holds trivially, but ② does not hold since not all objects currently existing will exist forever. Therefore, the converse Barcan formula is problematic.

The reason $L_P$ derives pathological propositions like the Barcan formulae is that TG is not valid for open formulae (TG is needed for the proof of Becker’s rule. That is, the problem in the proof is at step 2). As mentioned earlier, TG means that logically true propositions are true regardless of time. However, open formulae are neither true nor false. Open formulae are satisfied or not satisfied by particular objects.

To overcome this problem, one might propose restricting TG to apply only to closed formulae, but it is known that restricted temporal predicate logic fails to prove some desirable propositions. The task of creating a temporal predicate logic that is both sound and complete remains an unsolved problem.

텐서곱에 관한 노트

04 Mar 2025TL;DR. 벡터 공간의 텐서곱은 다음의 의미를 가진다.

- 다중 선형 사상의 선형화를 위한 정의역

- 다중 선형 사상의 공간

엄밀히 말해 1이 $U \otimes V$에 해당하고, 2는 $U^\ast \otimes V^\ast$이다. 하지만 혼용되는 경향이 있는 듯하다.

1. 도입

정의. $U, V, W$가 체 $\mathbb{F}$ 위에서 정의된 벡터 공간이라고 하자. $b: U \times V \to W$가 쌍선형 사상bilinear map이라는 것은 각 항에 대해서 $B$가 선형이라는 것이다. 즉, 임의의 $\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{u}_2 \in U, \mathbf{v}_1, \mathbf{v}_2 \in V$와 스칼라 $\alpha \in \mathbb{F}$에 대해 다음이 성립한다.

\[b(\alpha \mathbf{u}_1 + \mathbf{u}_2, \mathbf{v}_1) = \alpha b(\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{v}_1) + b(\mathbf{u}_2, \mathbf{v}_1)\] \[b(\mathbf{u}_1, \alpha \mathbf{v}_1 + \mathbf{v}_2) = \alpha b(\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{v}_1) + b(\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{v}_2)\]

예를 들어 실수 벡터 공간에서의 내적 $\cdot : V \times V \to \mathbb{R}$은, $\mathbb{R}$을 1차원 벡터 공간으로 간주했을 때 쌍선형 사상이다. 비슷한 방식으로 다중 선형 사상multilinear form을 정의할 수 있다. $V$가 $n$차원 벡터 공간일 때, $\mathrm{det}: V \times \dots \times V \to \mathbb{R}$은 $n$중 선형 사상이다.

$b: U \times V \to W$가 쌍선형 사상이라고 하자. 당연하게도 $b$는 선형 사상이 아니다. $b$는 서로 다른 두 공간의 벡터를 매개변수로 받는 사상이지, 한 공간의 벡터를 매개변수로 받는 사상이 아니기 때문이다. 설령 $b$를 직합 $U \oplus V$에서 $W$로 가는 사상으로 생각하더라도, $b(\alpha(u, v)) = b((\alpha u, \alpha v)) = \alpha^2 b(u, v)$이므로 선형성을 만족하지 않는다.

그러나 텐서곱을 이용하면 $b$를 선형 사상과 동일시할 수 있다.

2. 텐서곱의 정의

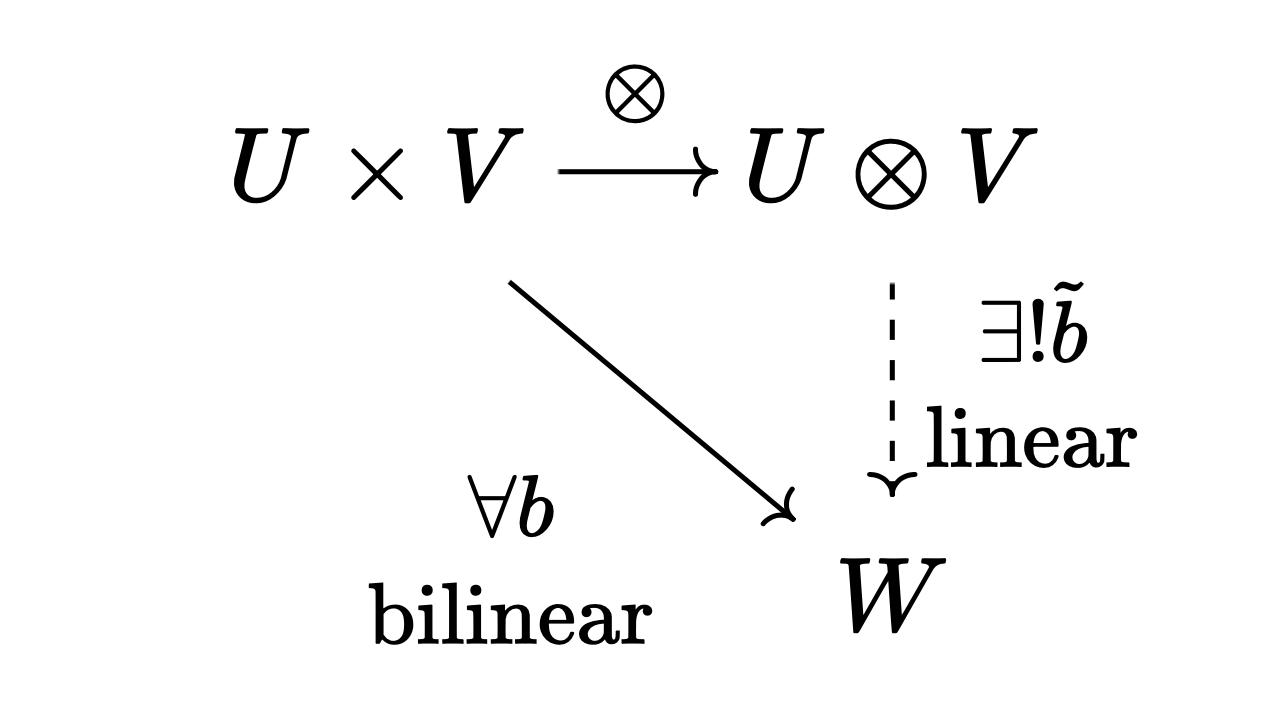

정의. 벡터 공간 $U, V$에 대해, 텐서곱tensor product $U \otimes V$를 다음 보편 성질universal property를 만족하는 벡터 공간으로 정의한다.

또한 $U \otimes V$의 원소를 텐서라고 한다.

정리. 임의의 벡터 공간의 텐서곱은 언제나 존재하며, 동형 사상에 대해 유일하다.

증명. 유한 차원 벡터 공간에 대해서만 증명한다. $U$와 $V$의 차원이 각각 $n, m$이고, 기저가 $\lbrace e_1, \dots, e_n\rbrace , \lbrace f_1, \dots, f_m\rbrace$이라고 하자. $T$가 차원이 $nm$인 벡터 공간이라고 하자. 차원이 같은 벡터 공간은 모두 동형이므로, 그러한 $T$는 동형 사상에 대해 유일하다. $T$의 형식적 기저를 다음과 같이 두자.

\[\mathcal{B} = \{ e_1f_1, \dots, e_1f_m, \dots, e_nf_1, \dots, e_nf_m \}\]$T$가 $U$와 $V$의 텐서곱임을 보이기 위해서 임의의 쌍선형 사상 $b: U \times V \to W$를 상정한다. $b$로부터 다음의 행벡터를 정의한다.

\[\tilde {b} = \big[ b(e_1, f_1), \dots, b(e_1, f_m), \dots, b(e_n, f_1), \dots, b(e_n, f_m) \big]_\mathcal{B}\]또한 $\otimes: V \times W \to T$를 다음과 같이 정의한다.

\[\otimes: (u, v) = (u_1e_1 + \dots + u_ne_n, v_1f_1 + \dots + v_mf_m) \mapsto \begin{bmatrix} u_1v_1 \\ \vdots \\ u_1v_m \\ \vdots \\ u_nv_1 \\ \vdots \\ u_nf_m \end{bmatrix}_{\mathcal{B}}\]이때 다음이 성립한다.

\[\begin{align} \tilde {b}(\otimes(u, v)) &= \sum_i \sum_j (u_i v_j)b(e_i, f_j) \\ &= b\left( \sum_i u_i e_i, \sum_j v_j f_j \right) && (\text{by bilinearity})\\ &= b(u, v) && \blacksquare \end{align}\]3. 텐서와 다중 선형 사상의 동일시

지금까지의 논의를 한 줄로 요약하면 다음과 같다.

\[\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, W) \cong \mathrm{Hom}(U \otimes V, W)\]여기서 $\mathrm{Hom}^2$은 쌍선형 사상의 공간을 의미한다. 특히 $W = \mathbb{F}$일 때, 쌍대 공간의 정의에 의해 다음이 성립한다.

\[\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F}) \cong \mathrm{Hom}(U \otimes V, \mathbb{F}) \cong (U \otimes V)^*\]이 관계를 이용하면 텐서곱을 쌍선형 사상의 선형화를 위한 정의역으로 보는 시각을 넘어, 쌍선형 사상의 공간 그 자체로 볼 수도 있다. 먼저 다음의 보조정리를 증명한다.

보조정리. $(U \otimes V)^\ast = U^\ast \otimes V^\ast$

증명. 앞선 관계식과 쌍대 공간의 정의로 인해 다음을 보이면 충분하다.

\[\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F}) \cong \mathrm{Hom}(U, \mathbb{F}) \otimes \mathrm{Hom}(V, \mathbb{F})\]즉, $\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F})$가 보편 성질을 만족함을 보이면 된다. 이는 앞선 증명과 거의 동일하므로 생략한다. ■

보조정리로부터 다음이 성립한다.

정리. $\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F}) \cong U^\ast \otimes V^\ast$

증명.

\[\begin{align} U^* \otimes V^* &\cong U^{***} \otimes V^{***} \\ &\cong (U^{**} \otimes V^{**})^* \\ &\cong (U \otimes V)^* \\ &\cong \mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F}) \end{align}\]두 번째 식에서 세 번째 식으로 넘어갈 때 $V \cong V^{\ast\ast}$ 표준canonical 동일시를 사용했다. ■

따라서 쌍대 공간의 텐서는 쌍선형 사상과 표준적으로 동일시할 수 있다.

Notes on Tensor Products

04 Mar 2025This post was originally written in Korean, and has been machine translated into English. It may contain minor errors or unnatural expressions. Proofreading will be done in the near future.

TL;DR. The tensor product of vector spaces has the following significance:

- A domain for the linearisation of multilinear maps

- A space of multilinear maps

Strictly speaking, 1 corresponds to $U \otimes V$, while 2 corresponds to $U^\ast \otimes V^\ast$. However, these appear to be used interchangeably.

1. Introduction

Definition. Let $U, V, W$ be vector spaces defined over a field $\mathbb{F}$. A map $b: U \times V \to W$ is called a bilinear map if $B$ is linear in each argument. That is, for any $\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{u}_2 \in U, \mathbf{v}_1, \mathbf{v}_2 \in V$ and scalar $\alpha \in \mathbb{F}$, the following hold:

\[b(\alpha \mathbf{u}_1 + \mathbf{u}_2, \mathbf{v}_1) = \alpha b(\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{v}_1) + b(\mathbf{u}_2, \mathbf{v}_1)\] \[b(\mathbf{u}_1, \alpha \mathbf{v}_1 + \mathbf{v}_2) = \alpha b(\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{v}_1) + b(\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{v}_2)\]

For example, the inner product $\cdot : V \times V \to \mathbb{R}$ in real vector spaces is a bilinear map when $\mathbb{R}$ is regarded as a one-dimensional vector space. Similarly, one can define multilinear forms. When $V$ is an $n$-dimensional vector space, $\mathrm{det}: V \times \dots \times V \to \mathbb{R}$ is an $n$-multilinear map.

Let $b: U \times V \to W$ be a bilinear map. Naturally, $b$ is not a linear map. This is because $b$ takes vectors from two different spaces as arguments, rather than vectors from a single space. Even if we consider $b$ as a map from the direct sum $U \oplus V$ to $W$, we have $b(\alpha(u, v)) = b((\alpha u, \alpha v)) = \alpha^2 b(u, v)$, which does not satisfy linearity.

However, using tensor products, we can identify $b$ with a linear map.

2. Definition of Tensor Products

Definition. For vector spaces $U, V$, the tensor product $U \otimes V$ is defined as the vector space satisfying the following universal property:

Elements of $U \otimes V$ are called tensors.

Theorem. The tensor product of any vector spaces always exists and is unique up to isomorphism.

Proof. We prove this only for finite-dimensional vector spaces. Suppose $U$ and $V$ have dimensions $n$ and $m$ respectively, with bases $\lbrace e_1, \dots, e_n\rbrace$ and $\lbrace f_1, \dots, f_m\rbrace$. Let $T$ be a vector space of dimension $nm$. Since vector spaces of the same dimension are isomorphic, such a $T$ is unique up to isomorphism. Let the formal basis of $T$ be:

\[\mathcal{B} = \{ e_1f_1, \dots, e_1f_m, \dots, e_nf_1, \dots, e_nf_m \}\]To show that $T$ is the tensor product of $U$ and $V$, consider an arbitrary bilinear map $b: U \times V \to W$. From $b$, define the following row vector:

\[\tilde {b} = \big[ b(e_1, f_1), \dots, b(e_1, f_m), \dots, b(e_n, f_1), \dots, b(e_n, f_m) \big]_\mathcal{B}\]Also define $\otimes: V \times W \to T$ as follows:

\[\otimes: (u, v) = (u_1e_1 + \dots + u_ne_n, v_1f_1 + \dots + v_mf_m) \mapsto \begin{bmatrix} u_1v_1 \\ \vdots \\ u_1v_m \\ \vdots \\ u_nv_1 \\ \vdots \\ u_nf_m \end{bmatrix}_{\mathcal{B}}\]Then the following holds:

\[\begin{align} \tilde {b}(\otimes(u, v)) &= \sum_i \sum_j (u_i v_j)b(e_i, f_j) \\ &= b\left( \sum_i u_i e_i, \sum_j v_j f_j \right) && (\text{by bilinearity})\\ &= b(u, v) && \blacksquare \end{align}\]3. Identification of Tensors with Multilinear Maps

The discussion thus far can be summarised in one line:

\[\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, W) \cong \mathrm{Hom}(U \otimes V, W)\]Here $\mathrm{Hom}^2$ denotes the space of bilinear maps. In particular, when $W = \mathbb{F}$, by the definition of dual spaces, the following holds:

\[\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F}) \cong \mathrm{Hom}(U \otimes V, \mathbb{F}) \cong (U \otimes V)^*\]Using this relationship, we can view tensor products not merely as domains for the linearisation of bilinear maps, but as spaces of bilinear maps themselves. First, we prove the following lemma.

Lemma. $(U \otimes V)^\ast = U^\ast \otimes V^\ast$

Proof. By the previous relationship and the definition of dual spaces, it suffices to show:

\[\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F}) \cong \mathrm{Hom}(U, \mathbb{F}) \otimes \mathrm{Hom}(V, \mathbb{F})\]That is, we need to show that $\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F})$ satisfies the universal property. This is almost identical to the previous proof, so we omit it. ■

From the lemma, the following holds:

Theorem. $\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F}) \cong U^\ast \otimes V^\ast$

Proof.

\[\begin{align} U^* \otimes V^* &\cong U^{***} \otimes V^{***} \\ &\cong (U^{**} \otimes V^{**})^* \\ &\cong (U \otimes V)^* \\ &\cong \mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F}) \end{align}\]In going from the second to the third expression, we used the canonical identification $V \cong V^{\ast\ast}$. ■

Therefore, tensors in dual spaces can be canonically identified with bilinear maps.

일반 공변성에 대한 노트

27 Feb 2025어떤 이론이 일반 공변적general covariant이라는 것은, 물리 법칙의 형태form가 미분가능한 좌표계 변환에 대해 보존된다는 것이다. 구체적으로, 좌표계 $\lbrace q_i \rbrace $와 좌표계 $\lbrace q’_i \rbrace $가 다음 관계에 있다고 하자.

\[q_i' = f_i(\{ q \})\]각 $i$에 대해 $f_i$가 미분 가능하다고 하자. 일반 공변적 이론이라면 좌표계 $\lbrace q_i \rbrace $를 사용했을 때와 좌표계 $\lbrace q_i’ \rbrace $를 사용했을 때의 물리 법칙이 형태가 같아야 한다.

예시를 보자. 퍼텐셜이 0인 계 안의 입자의 위치를 극좌표계 $(r, \theta)$ 또는 직교 좌표계 $(x, y)$를 사용하여 표현하는 경우를 생각해 보자. 두 좌표계는 다음 관계에 있다.

\[\begin{gather} x = f_1(r, \theta) = r \cos \theta\\ y = f_2(r, \theta) = r \sin \theta \end{gather}\]$f_1$과 $f_2$가 미분 가능하므로 일반 공변적 이론은 두 좌표계로 표현했을 때의 형태가 같아야 한다.

먼저 뉴턴 역학의 경우를 보자. 뉴턴 역학의 물리 법칙은 다음과 같다.

\[\begin{gather} -\frac{dV(x, y)}{dx} = m\ddot{x} \\ -\frac{dV(x, y)}{dy} = m\ddot{y} \end{gather}\]$V(x, y) = 0$이므로 $\ddot{x} = \ddot{y} = 0$이다. 즉 입자는 등속 선형 운동을 한다. 만약 뉴턴 역학이 일반 공변적이라면 위 법칙을 $(x, y)$에서 $(r, \theta)$로 바꿔 표현해도 결과가 같아야 한다.

\[\begin{gather} -\frac{dV(r, \theta)}{dr} = m\ddot{r} \\ -\frac{dV(r, \theta)}{d\theta} = m\ddot{\theta} \end{gather}\]$V(r, \theta) = 0$이므로 $\ddot{r} = \ddot{\theta} = 0$이다. 이번에는 입자가 등속 원운동을 한다. 결과가 달라졌으므로 뉴턴 역학은 일반 공변적이지 않다.

이제 라그랑주 역학의 경우를 보자. 라그랑주 역학의 물리 법칙은 다음과 같다.

\[\begin{gather} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial x} = \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{x}} \\ \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial y} = \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{y}} \end{gather}\]$\mathcal{L}(x, y) = T - V = \frac{m}{2}(\dot{x}^2 + \dot{y}^2)$를 대입하면 $\ddot{x} = \ddot{y} = 0$, 즉 등속 선형 운동을 얻는다. 여기까지는 뉴턴 역학과 같다.

이제 오일러-라그랑주 방정식의 $(x, y)$를 $(r, \theta)$로 치환해 보자.

\[\begin{gather} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial r} = \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{r}} \\ \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \theta} = \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{\theta}} \end{gather}\]$x = r\cos\theta, y = r\sin\theta$를 대입하여 정리하면 $\mathcal{L}(r, \theta)$는 다음과 같다.

\[\mathcal{L}(r, \theta) = \frac{m}{2}(\dot{r}^2 + r^2 \dot{\theta}^2)\]Remark. 오일러-라그랑주 방정식에서는 단순히 $(x, y)$를 $(r, \theta)$로 치환했지만, 라그랑지안에서는 $x = r \cos \theta, y = r \sin \theta$ 관계식을 대입하는 이유는 라그랑지안이 실수쌍에 대한 함수가 아니라 시공간의 점에 대한 함수이기 때문이다. 일반 공변성은 무지성, 일편단률적인 좌표 변환에 대해서 식의 형태가 유지된다는 의미가 아니라, 물리계를 표현하는 함수들은 유지된 채 그것을 표현하는 좌표가 바뀌었을 때 식의 형태가 유지된다는 의미이다.

대입하여 계산하면 다음과 같다.

\[\begin{gather} \ddot{r} = r\dot{\theta}^2 \\ 2\dot{r}\dot{\theta} + r\ddot{\theta} = 0 \end{gather}\]미분방정식이 복잡해서 알아보기 힘들지만, 위 두 미분방정식은 $\ddot{x} = \ddot{y} = 0$과 동치이다. 일례로 $\theta = \tan^{-1}t, r = \sqrt{1 + t^2}$가 방정식의 해인 것을 확인할 수 있다.

일반적으로 다음이 성립한다.

정리. 라그랑주 역학은 일반 공변성을 가진다.

뉴턴 역학은 일반 공변성이 없지만 라그랑주 역학은 있다는 것이 신기하게 느껴질 수 있지만, 잘 생각해 보면 이것은 당연하다. 뉴턴의 제1법칙은 보통 $F = 0 \implies \ddot{x} = 0$이라는 수식으로 표현되지만 정확한 진술은 다음과 같다.

외력을 받지 않는 입자의 시공간 다이어그램은 선형이다.

‘선형’이라는 표현에 주목하라. 선형성은 특정한 기하학에 의존적인 표현이다. 예를 들어 유클리드 기하학에서 ‘선형’이란 우리가 흔히 말하는 직선이지만, 구면 기하학에서 ‘선형’은 대원으로 주어진다. 그러므로 위 진술은 다음과 같이 밝혀 쓰는 것이 가장 정확하다.

뉴턴 역학. 외력을 받지 않는 입자의 시공간 다이어그램은 유클리드 기하학의 선형이다.

그리고 유클리드 기하학의 선형은 직교 좌표계에서 $\ddot{x} = \ddot{y} = 0$ 꼴로 주어진다. 따라서 $F = 0 \implies \ddot{x} = 0$은, 유클리드 기하학과 직교 좌표계를 전제했을 때에만 올바른 수식인 것이다.

거꾸로 말해, 이론이 특정한 기하학에 의존하지 않는다면 그 이론은 일반 공변적이다. 라그랑주 역학은 그러한 이론의 사례이다. 라그랑주 역학의 진술은 다음과 같이 표현할 수 있다.

라그랑주 역학. 라그랑지안의 적분을 극화시키는 경로가 입자의 운동 경로이다.

그리고 라그랑지안은 특정 기하학에 의존적인 함수가 아닌, 그저 시공간의 점들에 대해 실숫값을 출력하는 함수이다. 따라서 위 진술은 어떠한 기하학에 대해서도 의존적이지 않으며, 라그랑주 역학은 일반 공변적이다.

구멍 논증hole argument에 따르면 일반 공변적인 이론들은 형이상학적인 의미에서 비결정론적이다. 이에 대한 설명은 나중에 하도록 하겠다.

Notes on General Covariance

27 Feb 2025This post was originally written in Korean, and has been machine translated into English. It may contain minor errors or unnatural expressions. Proofreading will be done in the near future.

A theory is said to be general covariant when the form of physical laws is preserved under differentiable coordinate transformations. Specifically, suppose coordinate systems $\lbrace q_i \rbrace$ and $\lbrace q’_i \rbrace$ are related by:

\[q_i' = f_i(\{ q \})\]Let each $f_i$ be differentiable for all $i$. If a theory is generally covariant, then the physical laws must have the same form when using coordinate system $\lbrace q_i \rbrace$ as when using coordinate system $\lbrace q_i’ \rbrace$.

Consider an example. Suppose we describe the position of a particle in a system with zero potential using either polar coordinates $(r, \theta)$ or Cartesian coordinates $(x, y)$. The two coordinate systems are related by:

\[\begin{gather} x = f_1(r, \theta) = r \cos \theta\\ y = f_2(r, \theta) = r \sin \theta \end{gather}\]Since $f_1$ and $f_2$ are differentiable, a generally covariant theory must have the same form when expressed in both coordinate systems.

First, consider the case of Newtonian mechanics. The physical laws of Newtonian mechanics are:

\[\begin{gather} -\frac{dV(x, y)}{dx} = m\ddot{x} \\ -\frac{dV(x, y)}{dy} = m\ddot{y} \end{gather}\]Since $V(x, y) = 0$, we have $\ddot{x} = \ddot{y} = 0$. That is, the particle undergoes uniform linear motion. If Newtonian mechanics were generally covariant, then expressing the above laws in terms of $(r, \theta)$ instead of $(x, y)$ should yield the same result.

\[\begin{gather} -\frac{dV(r, \theta)}{dr} = m\ddot{r} \\ -\frac{dV(r, \theta)}{d\theta} = m\ddot{\theta} \end{gather}\]Since $V(r, \theta) = 0$, we have $\ddot{r} = \ddot{\theta} = 0$. This time, the particle undergoes uniform circular motion. Since the results differ, Newtonian mechanics is not generally covariant.

Now consider the case of Lagrangian mechanics. The physical laws of Lagrangian mechanics are:

\[\begin{gather} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial x} = \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{x}} \\ \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial y} = \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{y}} \end{gather}\]Substituting $\mathcal{L}(x, y) = T - V = \frac{m}{2}(\dot{x}^2 + \dot{y}^2)$ yields $\ddot{x} = \ddot{y} = 0$, i.e., uniform linear motion. This is the same as in Newtonian mechanics thus far.

Now let us substitute $(r, \theta)$ for $(x, y)$ in the Euler-Lagrange equations:

\[\begin{gather} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial r} = \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{r}} \\ \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \theta} = \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{\theta}} \end{gather}\]Substituting $x = r\cos\theta, y = r\sin\theta$ and simplifying, $\mathcal{L}(r, \theta)$ becomes:

\[\mathcal{L}(r, \theta) = \frac{m}{2}(\dot{r}^2 + r^2 \dot{\theta}^2)\]Remark. while in the Euler-Lagrange equations we simply substitute $(r, \theta)$ for $(x, y)$, in the Lagrangian we substitute the relation $x = r \cos \theta, y = r \sin \theta$ because the Lagrangian is not a function of pairs of real numbers but rather a function of points in spacetime. General covariance does not mean that the form of equations is preserved under mindless, uniform coordinate transformations, but rather that when the functions describing a physical system are maintained while the coordinates expressing them are changed, the form of equations is preserved.

Substituting and calculating yields:

\[\begin{gather} \ddot{r} = r\dot{\theta}^2 \\ 2\dot{r}\dot{\theta} + r\ddot{\theta} = 0 \end{gather}\]Although the differential equations are complex and difficult to interpret, the above two differential equations are equivalent to $\ddot{x} = \ddot{y} = 0$. For instance, one can verify that $\theta = \tan^{-1}t, r = \sqrt{1 + t^2}$ is a solution to the equations.

In general, the following holds:

Theorem. Lagrangian mechanics possesses general covariance.

It may seem surprising that Newtonian mechanics lacks general covariance while Lagrangian mechanics possesses it, but upon reflection, this is quite natural. Newton’s first law is commonly expressed mathematically as $F = 0 \implies \ddot{x} = 0$, but the precise statement is:

The spacetime diagram of a particle not subject to external forces is linear.

Note the expression ‘linear’. Linearity is a concept dependent upon specific geometry. For example, in Euclidean geometry, ‘linear’ refers to what we commonly call a straight line, but in spherical geometry, ‘linear’ is given by great circles. Therefore, the above statement is most accurately written as:

Newtonian mechanics. The spacetime diagram of a particle not subject to external forces is linear in Euclidean geometry.

Linear motion in Euclidean geometry is given by $\ddot{x} = \ddot{y} = 0$ in Cartesian coordinates. Therefore, $F = 0 \implies \ddot{x} = 0$ is a correct equation only when Euclidean geometry and Cartesian coordinates are presupposed.

Conversely, if a theory does not depend upon specific geometry, then that theory is generally covariant. Lagrangian mechanics is an example of such a theory. The statement of Lagrangian mechanics can be expressed as:

Lagrangian mechanics. The path that extremises the integral of the Lagrangian is the particle’s trajectory.

The Lagrangian is not a function dependent upon specific geometry, but merely a function that outputs real values for points in spacetime. Therefore, the above statement is not dependent upon any particular geometry, and Lagrangian mechanics is generally covariant.

According to the hole argument, generally covariant theories are indeterministic in a metaphysical sense. An explanation of this will be provided later.

오일러-라그랑주 방정식과 라그랑주 역학

27 Feb 20251. 도입

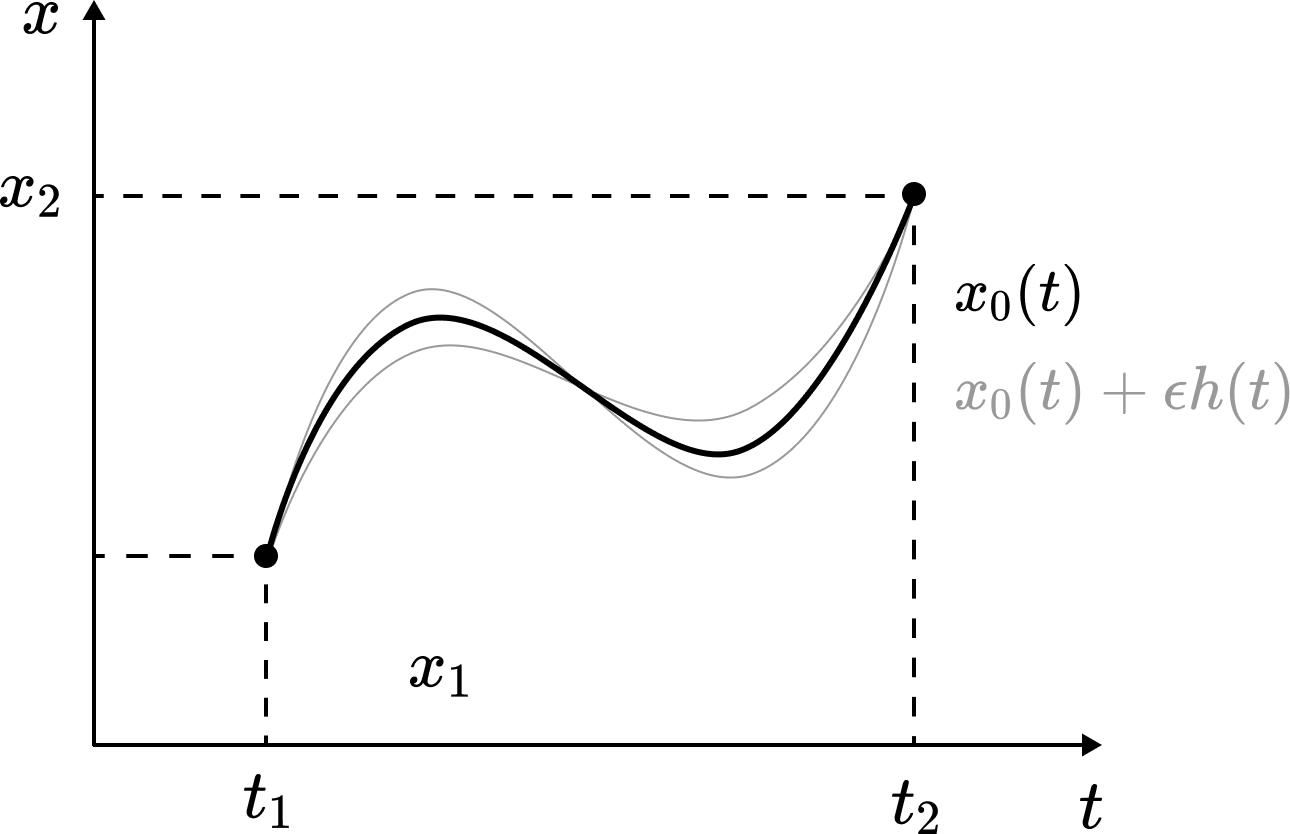

1차원 위에서 운동하는 입자의 운동 경로는 $x(t)$와 같이 표현할 수 있다. 입자의 위치와 속도에 의존적인 함수 $f(x, x’)$를 생각하자. 이 입자가 시간 $t_1$일 때 $x_1$에서 출발하여 시간 $t_2$일 때 $x_2$에 도착하는데, 그 과정에서 다음 값을 극화extremise하는 경로, 즉 다음 값이 극대 또는 극소가 되도록 하는 경로 $x(t)$를 찾는 것이 목표이다.

\[A[x] = \int^{t_2}_{t_1} f(x, \dot{x}) dt\]대괄호는 $A$의 매개변수가 실수가 아닌 함수임을 의미한다. 따라서 직관적으로 생각했을 때 $A[x]$를 최소화하는 $x(t)$를 찾기 위해서는 함수에 대한 미분식을 세워야 한다.

\[\frac{dA[x]}{dx(t)} = 0?\]2. 오일러-라그랑주 방정식

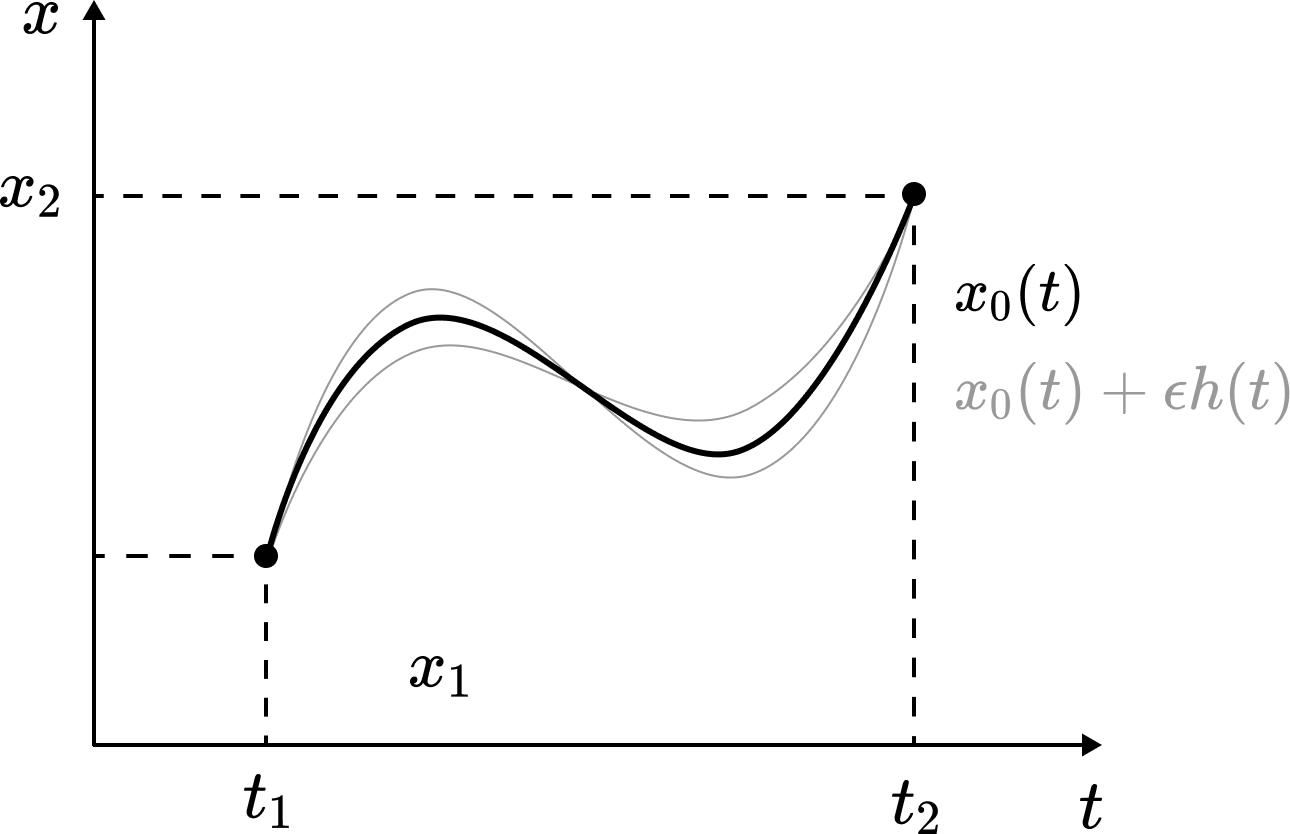

물론 함수에 대한 미분을 우리는 정의한 적이 없다. 하지만 간단한 트릭을 통해 함수에 대한 미분을 일반적인 미분으로 환원할 수 있다. 먼저 $x_0(t)$가 우리가 찾고자 하는 경로, 즉 $A[x]$를 극화시키는 경로라고 하자. $x_0(t)$의 ‘주변’에 있는 경로는 다음과 같은 꼴이다.

\[x(\alpha, t) = x_0(t) + \alpha h(t)\]

경계 조건은 $h(t_1) = h(t_2) = 0$이다. $x_0(t)$가 $A[x]$를 극화시키므로, 충분히 작은 $\epsilon$에 대해 $A[x_0] = A[x(0, t)] \leq A[x(\epsilon, t)]$이다. 따라서,

\[\left. \frac{dA[x(\alpha, t)]}{d\alpha} \right\vert_{\alpha = 0} = 0\]위 식을 전개하면 다음과 같다.

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{dA}{d\alpha} &= \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{d}{d\alpha} \Big[ f \big( x(\alpha, t), \dot{x}(\alpha, t) \big) \Big] dt \\ &= \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} + \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}}\frac{\partial \dot{x}}{\partial \alpha} \right) dt \\ &= \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} dt + \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \cdot \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} \right) dt \\ &= \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} dt + \left[ \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} \right]^{t_2}_{t_1} - \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \right) \frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} dt \end{aligned}\]3번 식에서 4번 식으로 넘어가는 데 부분적분이 쓰였다. ${\partial x}/{\partial \alpha} = h(t)$이므로, 경계 조건에 의해 4번 식의 두 번째 항은 소거된다. 따라서,

\[\frac{dA}{d\alpha} = \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} - \frac{d}{dt}\left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \right) \right) \frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} dt = 0\]임의의 $h \in C^1$에 대해 위 식이 만족되어야 하므로, $x(t)$가 $A$를 극화할 다음의 필요조건을 얻는다.

\[\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = \frac{d}{dt}\left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \right)\]이것이 오일러-라그랑주 방정식Euler-Lagrange equation이다. 값 $A$를 극화한다는 것을 $\delta A = 0$과 같이 표현하므로, 오일러-라그랑주 방정식의 결론은 다음과 같이 적을 수 있다.

\[\delta A = 0 \implies \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = \frac{d}{dt}\left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \right)\]방금 우리는 일변수 함수에 대해 증명했지만, 다변수 함수에 대해서도 마찬가지 식이 성립한다. 즉, 어떤 입자(들)의 운동을 나타내는 좌표가 $\lbrace q_i \rbrace _{i \leq n}$라고 하자. 예를 들어 2개의 입자가 3차원에서 운동하는 경우 $n = 6$이다. 이들의 운동이 $\int f(q_1, \dot{q_1}, \dots, q_n, \dot{q_n}) dt$를 극화할 필요조건은 각 $i$에 대해 다음이 성립하는 것이다.

\[\frac{\partial f}{\partial q_i} = \frac{d}{dt}\left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{q_i}} \right)\]3. 라그랑주 역학

정의. 계 $S$의 입자(들)의 운동을 나타내는 좌표가 $\lbrace q_i \rbrace _{1 \leq i \leq n}$라고 하자. $S$의 라그랑지안Lagrangian $\mathcal{L}(\lbrace q , \dot{q} \rbrace, t)$를, 다음의 값을 극화시키는 조건에 대한 방정식이 입자들의 운동 방정식과 같아지도록 하는 함수로 정의한다.

\[\mathcal{S} = \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \mathcal{L}(\{ q, \dot{q} \}, t) dt\]$\mathcal{S}$를 작용action이라고 부른다.

예를 들어 1차원 퍼텐셜 장 $V(x)$에 속하는 입자의 라그랑지안은 다음과 같다.

\[\begin{aligned} \mathcal{L}(x, \dot{x}) &= T - V \\ &= \frac{1}{2}m\dot{x}^2 - V(x) \end{aligned}\]위 함수가 라그랑지안이라는 것을 확인해 보자. 오일러-라그랑주 방정식을 사용하면 해당 라그랑지안에 따른 작용이 극화될 조건은 다음과 같다.

\[\begin{aligned} \delta \mathcal{S} = 0 &\implies \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial x} = \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{x}} \\ &\iff -\frac{dV}{dx} = \frac{d}{dt}(m\dot{x}) \\ &\iff -\frac{dV}{dx} = m\ddot{x} \end{aligned}\]마지막 식은 뉴턴의 운동 방정식이다. 따라서 $\mathcal{L}$은 이 계의 라그랑지안이 맞다. 일반적으로 다음이 성립한다.

정리. 다음 두 조건을 만족하는 고전역학적 계의 라그랑지안은 $\mathcal{L} = T - V$로 주어진다.

- 계의 경계 조건이 홀로노믹holonomic하다. 즉, 경계 조건이 입자들의 위치에만 의존하고 속도에 의존하지 않는다.

- 계에 작용하는 힘 $\mathbf{F}_i$가 퍼텐셜 함수 $U_i(\lbrace q, \dot{q} \rbrace, t)$를 가진다.

증명. 링크된 SE 포스트를 참조.

그러나 일반적으로 계의 라그랑지안이 $T - V$로 주어지는 것은 아니다. 예를 들어 상대론적 입자의 운동 에너지는 $(\gamma - 1)m_0c^2$이지만, 올바른 라그랑지안은 $-m_0c^2/\gamma$이다.

뉴턴 역학과 달리 라그랑주 역학은 매우 자유로운 좌표계 변환을 허용한다는 점에서 강점을 가진다. 뉴턴 역학과 달리 라그랑주 역학은 일반 공변성을 가지기 때문이다. 이에 대한 자세한 설명은 다음 글에 있다.

The Euler-Lagrange Equation and Lagrangian Mechanics

27 Feb 2025This post was originally written in Korean, and has been machine translated into English. It may contain minor errors or unnatural expressions. Proofreading will be done in the near future.

1. Introduction

The trajectory of a particle moving in one dimension can be expressed as $x(t)$. Consider a function $f(x, x’)$ that depends on the particle’s position and velocity. Our objective is to find the path $x(t)$ along which the particle travels from position $x_1$ at time $t_1$ to position $x_2$ at time $t_2$, such that the following quantity is extremised—that is, the path that renders this quantity either maximum or minimum:

\[A[x] = \int^{t_2}_{t_1} f(x, \dot{x}) dt\]The square brackets indicate that the parameter of $A$ is a function rather than a real number. Therefore, intuitively, to find $x(t)$ that minimises $A[x]$, we should establish a differential equation for functions.

\[\frac{dA[x]}{dx(t)} = 0?\]2. The Euler-Lagrange Equation

Of course, we have never defined differentiation with respect to functions. However, through a simple trick, we can reduce differentiation with respect to functions to ordinary differentiation. First, let $x_0(t)$ be the path we seek—that is, the path that extremises $A[x]$. A path in the ‘neighbourhood’ of $x_0(t)$ takes the following form:

\[x(\alpha, t) = x_0(t) + \alpha h(t)\]

The boundary conditions are $h(t_1) = h(t_2) = 0$. Since $x_0(t)$ extremises $A[x]$, for sufficiently small $\epsilon$, we have $A[x_0] = A[x(0, t)] \leq A[x(\epsilon, t)]$. Therefore,

\[\left. \frac{dA[x(\alpha, t)]}{d\alpha} \right\vert_{\alpha = 0} = 0\]Expanding the above equation yields:

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{dA}{d\alpha} &= \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{d}{d\alpha} \Big[ f \big( x(\alpha, t), \dot{x}(\alpha, t) \big) \Big] dt \\ &= \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} + \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}}\frac{\partial \dot{x}}{\partial \alpha} \right) dt \\ &= \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} dt + \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \cdot \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} \right) dt \\ &= \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} dt + \left[ \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} \right]^{t_2}_{t_1} - \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \right) \frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} dt \end{aligned}\]Integration by parts is employed in the transition from the third to the fourth equation. Since ${\partial x}/{\partial \alpha} = h(t)$, the second term in the fourth equation vanishes due to the boundary conditions. Therefore,

\[\frac{dA}{d\alpha} = \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} - \frac{d}{dt}\left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \right) \right) \frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} dt = 0\]Since the above equation must be satisfied for arbitrary $h \in C^1$, we obtain the following necessary condition for $x(t)$ to extremise $A$:

\[\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = \frac{d}{dt}\left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \right)\]This is the Euler-Lagrange equation. Since extremising the value $A$ is expressed as $\delta A = 0$, the conclusion of the Euler-Lagrange equation can be written as follows:

\[\delta A = 0 \implies \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = \frac{d}{dt}\left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \right)\]We have just proved this for functions of one variable, but the same equation holds for functions of multiple variables. That is, let the coordinates representing the motion of some particle(s) be $\lbrace q_i \rbrace _{i \leq n}$. For example, if two particles move in three dimensions, then $n = 6$. The necessary condition for their motion to extremise $\int f(q_1, \dot{q_1}, \dots, q_n, \dot{q_n}) dt$ is that the following holds for each $i$:

\[\frac{\partial f}{\partial q_i} = \frac{d}{dt}\left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{q_i}} \right)\]3. Lagrangian Mechanics

Definition. Let the coordinates representing the motion of the particles in system $S$ be $\lbrace q_i \rbrace _{1 \leq i \leq n}$. The Lagrangian $\mathcal{L}(\lbrace q , \dot{q} \rbrace, t)$ of $S$ is defined as a function such that the equation for the condition that extremises the following quantity becomes identical to the equations of motion of the particles:

\[\mathcal{S} = \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \mathcal{L}(\{ q, \dot{q} \}, t) dt\]$\mathcal{S}$ is called the action.

For example, the Lagrangian of a particle in a one-dimensional potential field $V(x)$ is as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathcal{L}(x, \dot{x}) &= T - V \\ &= \frac{1}{2}m\dot{x}^2 - V(x) \end{aligned}\]Let us verify that the above function is indeed the Lagrangian. Using the Euler-Lagrange equation, the condition for the action corresponding to this Lagrangian to be extremised is as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} \delta \mathcal{S} = 0 &\implies \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial x} = \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{x}} \\ &\iff -\frac{dV}{dx} = \frac{d}{dt}(m\dot{x}) \\ &\iff -\frac{dV}{dx} = m\ddot{x} \end{aligned}\]The final equation is Newton’s equation of motion. Therefore, $\mathcal{L}$ is indeed the Lagrangian of this system. In general, the following holds:

Theorem. The Lagrangian of a classical mechanical system satisfying the following two conditions is given by $\mathcal{L} = T - V$:

- The constraints of the system are holonomic. That is, the constraints depend only on the positions of the particles and not on their velocities.

- The forces $\mathbf{F}_i$ acting on the system have potential functions $U_i(\lbrace q, \dot{q} \rbrace, t)$.

Proof. See the linked SE post.

However, in general, the Lagrangian of a system is not necessarily given by $T - V$. For instance, while the kinetic energy of a relativistic particle is $(\gamma - 1)m_0c^2$, the correct Lagrangian is $-m_0c^2/\gamma$.

Unlike Newtonian mechanics, Lagrangian mechanics has the advantage of permitting very flexible coordinate transformations. This is because, unlike Newtonian mechanics, Lagrangian mechanics possesses general covariance. A detailed explanation of this can be found in the following article.

르베그 가측 집합과 보렐 가측 집합

25 Feb 20251. 르베그 측도

카라테오도리 정리로부터 다음과 같이 측도 $m$을 정의할 수 있다.

-

$\mathcal{A}_0 = \lbrace \cup^n_{k=1} (a_k, b_k] : a_k, b_k \in \mathbb{R}^\infty \rbrace $는 대수임을 보인다.

-

$A \in \mathcal{A}_0$에 대해, $A = \sqcup^n_{k=1} (a_k, b_k]$로 표현하는 방법이 유일함을 보인다.

-

함수 $\rho: \mathcal{A}_0 \to [0, \infty]$를

\[\rho(\sqcup^n_{k=1} (a_k, b_k]) = \sum^n_{k=1}(b_k - a_k)\]와 같이 정의했을 때 $\rho$가 예비측도임을 보인다.

-

$\mathcal{A}_0, \rho$에 대해 카라테오도리 구축 정리를 적용하여 외측도 $m^\ast$을 얻는다.

-

$m^\ast$의 정의역을 $m^\ast$-가측집합으로 제한하여 측도 $m$을 얻는다.

대수는 유한 합집합에만 닫혀 있기 때문에 1, 2, 3은 거의 자명하다. 4, 5의 증명은 관련 글을 참조하라.

정의. 상술한 $m$을 르베그 측도Lebesgue measure라고 부른다. 또한, $m$의 정의역에 속하는 집합을 르베그 가측Lebesgue measurable이라고 부른다.

카라테오도리 정리들로부터 다음 사실들이 어렵지 않게 따라 나온다.

정리.

- $m([a, b]) = m((a, b)) = m((a, b]) = m([a, b)) = b - a$

- $A \subset \mathbb{R}$이 가산일 때, $m(A) = 0$

그리고 카라테오도리 확장 정리로 얻어지는 측도는 완비 측도complete measure이므로 다음이 성립한다.

정리. $m$은 완비 측도이다.

또한 $\sigma(\mathcal{A}_0)$는 보렐 $\sigma$-대수 $\mathcal{B}$이므로, 다음이 따라 나온다.

정리. 보렐 가측 집합은 르베그 가측이다.

2. 르베그 가측이지만 보렐 가측이 아닌 집합

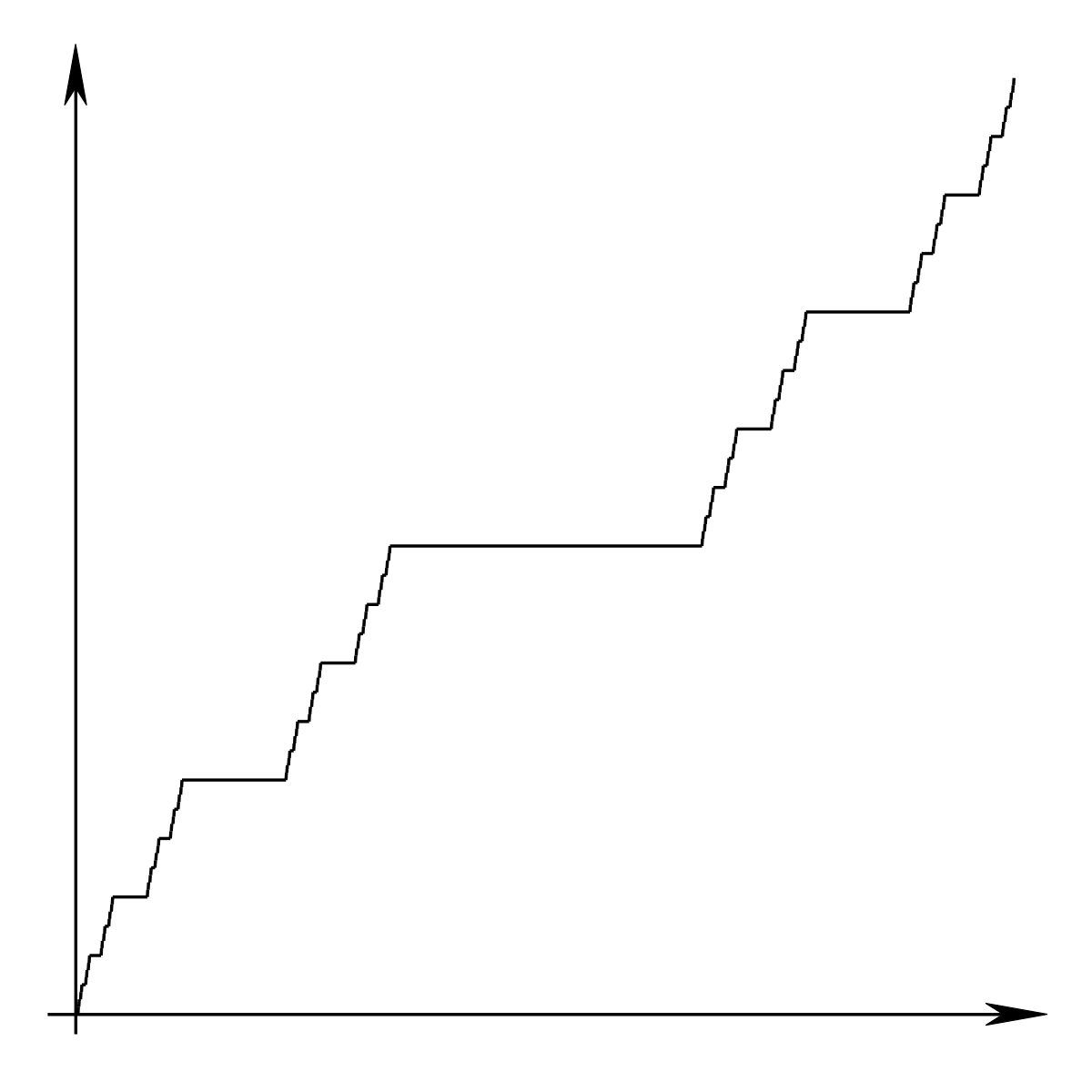

정의. 집합열 $\lbrace C_n \rbrace$을 다음과 같이 정의한다.

\[\begin{gather} C_0 = [0, 1]\\ C_1 = I_0 \setminus (1/3, 2/3) \\ C_2 = I_1 \setminus \{ (1/9, 2/9) \cup (7/9, 8/9) \} \\ \vdots \end{gather}\]칸토어 집합Cantor set $C$를 $\cap^\infty_{n = 0}C_n$으로 정의한다.

정리.

- 칸토어 집합은 비가산이다.

- 칸토어 집합은 르베그 측도 0이다.

증명.

-

칸토어 집합에 속하는 원소들은 삼진법으로 소숫점 전개했을 때 어느 자리에도 2가 등장하지 않는 수들이다. 그러한 수는 $2^\aleph_0$개 있으므로 비가산이다.

-

$m(C_n) = (2/3)^n$이므로 $m(C) = \lim_{n \to infty} (2/3)^n = 0$. ■

정의. 칸토어 집합을 정의할 때 각 단계에서 빠지는 집합을 $J_n$이라고 하자. 즉,

\[\begin{gather} J_1 = (1/3, 2/3) \\ J_2 = (1/9, 2/9) \cup (7/9, 8/9) \\ \vdots \end{gather}\]다음과 같이 함수열을 정의한다.

\[\begin{gather} \operatorname{dom} f_1 = J_1,\; f_1(x) = \frac{1}{2} \\\\ \operatorname{dom} f_2 = J_1 \cup J_2, \; f_2(x) = \begin{cases} 1/4 & x \in (1/9, 2/9) \\ 1/2 & x \in (1/3, 2/3) \\ 3/4 & x \in (7/9, 8/9) \end{cases} \\\\ \vdots \end{gather}\]$f: I \to I$를 다음과 같이 정의한다.

\[f(x) = \inf \{ f_n(y) : y \geq x, y \in \mathrm{dom} f \}\]$f$를 칸토어 함수Cantor function라고 한다.

정리. 칸토어 함수는 연속이다.

증명. $f$를 칸토어 함수라고 하자. $f$는 증가함수이므로 $f$가 불연속점을 가진다면 해당 불연속은 틈 불연속gap discontinuity이며, 따라서 어떤 $\epsilon > 0$와 $y_0 \in I$에 대해 $(y_0 - \epsilon, y_0 + \epsilon)$이 $\operatorname{im} f$ 밖에 속한다. 그런데 $(y_0 - \epsilon, y_0 + \epsilon)$의 원소 중에는 이진법으로 소숫점 전개했을 때 자릿수가 유한한 수가 존재한다. 해당 수는 $\operatorname{im}f$에 속하므로 모순이다. ■

정리. 르베그 가측이지만 보렐 가측이 아닌 함수가 존재한다.

증명.

보조정리. $f$가 증가함수라면 $f^{-1}$은 보렐 집합을 보렐 집합에 사상한다.

보조정리의 증명. $\mathcal{A} = \lbrace S \subset I : f^{-1}(S) \in \mathcal{B} \rbrace $라고 하자. 열린 집합들의 모음 $\mathcal{G}$에 대해 $\mathcal{G} \subset \mathcal{A}$임이 자명하다. 또한 $\mathcal{A}$가 $\sigma$-대수임이 역함수의 성질로부터 자명하다. 따라서 $\mathcal{A} = \sigma(\mathcal{G}) = \mathcal{B}$이다.

$f$가 칸토어 함수라고 하고, $F$를 다음과 같이 정의하자.

\[F(x) =\inf \{y : f(y) \geq x \}\]$F$는 엄격히 증가하는 함수이고, $\operatorname{im} F = C$이다($C$는 칸토어 집합). $V$를 비탈리 집합이라고 하자. $F[V]$는 $C$에 포함되므로 르베그 측도 0이며, 르베그 측도의 완비성에 따라 르베그 가측이다. 그러나 $F[V]$는 보렐 가측이 아니다. 만약 보렐 가측이었다면 $F$가 증가함수이므로 $F^{-1}(F[V]) = V$가 가측이어야 하기 때문이다. ■