Fréchet Filters and Nonstandard Natural Numbers

22 Jan 2025Löwenheim-Skolem theorem states that there exist models that are elementarily equivalent yet nonisomorphic to the standard model of arithmetics. In other words, there exist number systems that satisfy all first-order sentences of arithmetics, yet are not “the” natural numbers.

In this article, we construct the hypernaturals, a representative nonstandard model of arithmetic, using ultraproducts, and prove Łoś’s theorem, which states that this model is elementarily equivalent to the standard model of arithmetics.

1. Overview

By the compactness theorem, we know that first-order logic cannot distinguish between the finite and the infinite. Therefore, we might reasonably expect to be able to define a model that is indistinguishable from the standard model with respect to every first-order formula by a clever use of infinity.

To this end, we may tro to define the hypernaturals $[0], [1], [2], \dots$ as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} [0] &= (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, \dots) \\ [1] &= (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, \dots) \\ [2] &= (2, 2, 2, 2, 2, \dots) \end{aligned}\]This definition makes sense, but upon reflection, requiring all entries to be 0 in order to regard it as $[0]$ is excessively stringent. For instance, it would be natural to regard the tuple $(1, 1, 0, 0, 0, \dots)$, where the only the first two entries are nonzero, as $[0]$ as well. Therefore, let us consider a tuple as $[n]$ if all but finitely many entries equal $n$. That is,

\[[n] = \lbrace (x_1, x_2, x_3, \dots) \in \mathbb{N}^\omega : \lbrace i \in \mathbb{N}: x_i \neq n \rbrace \text{ is finite} \rbrace\]However, this now gives rise to the following problem. Should the following tuple be considered as $[0]$ or as $[1]$?

\[(0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, \dots)\]To resolve this ambiguity, we shall arbitrarily choose one among the set of even numbers and the set of odd numbers. If we choose the even numbers, the above tuple becomes $[0]$ (indices begin at 0), while if we choose the odd numbers it becomes $[1]$.

This “choosing” requires some intricacy. For example, if the set of multiples of 6 is chosen, then the set of multiples of 3 must also be chosen for consistency, since tuples satisfying the latter trivially satisfy the former. Moreover, since the set of multiples of 3 is chosen, the set of numbers that are not multiples of 3 must be rejected. The end result of this process of choosing and rejecing for all subsets of the natural numbers will give rise to a structure called an ultrafilter. Given an appropriate ultrafilter, we can map any tuple to a hypernatural, and this entire process is called an ultraproduct.

2. Definition of Ultrafilters

Definition. Let $X$ be a set. A collection $\mathcal{F}$ of subsets of $X$ is called a filter on $X$ if it satisfies the following:

- $X \in \mathcal{F}$

- $\varnothing \not\in \mathcal{F}$

- Upward closure: $A \in \mathcal{F}, A \subset B \implies B \in \mathcal{F}$

- Finite intersection closure: $A, B \in \mathcal{F} \implies A \cap B \in \mathcal{F}$

Intuitively, a filter is a “collection of large sets”. From this perspective, axioms 1 and 2 express the trivial principle that the whole set is large and the empty set is small. Axiom 3 expresses the principle that a set containing a large set is large, while axiom 4 expresses the principle that finite intersections of large sets remain large.

As a side note, filters are used not only in ultraproducts but also in converting models of fuzzy logic into models of classical logic. In this context, filters become “collections of true statements” rather than “collections of large sets”. And indeed, the conversion from fuzzy logic to classical logic is also one way of understanding Cohen’s forcing method.

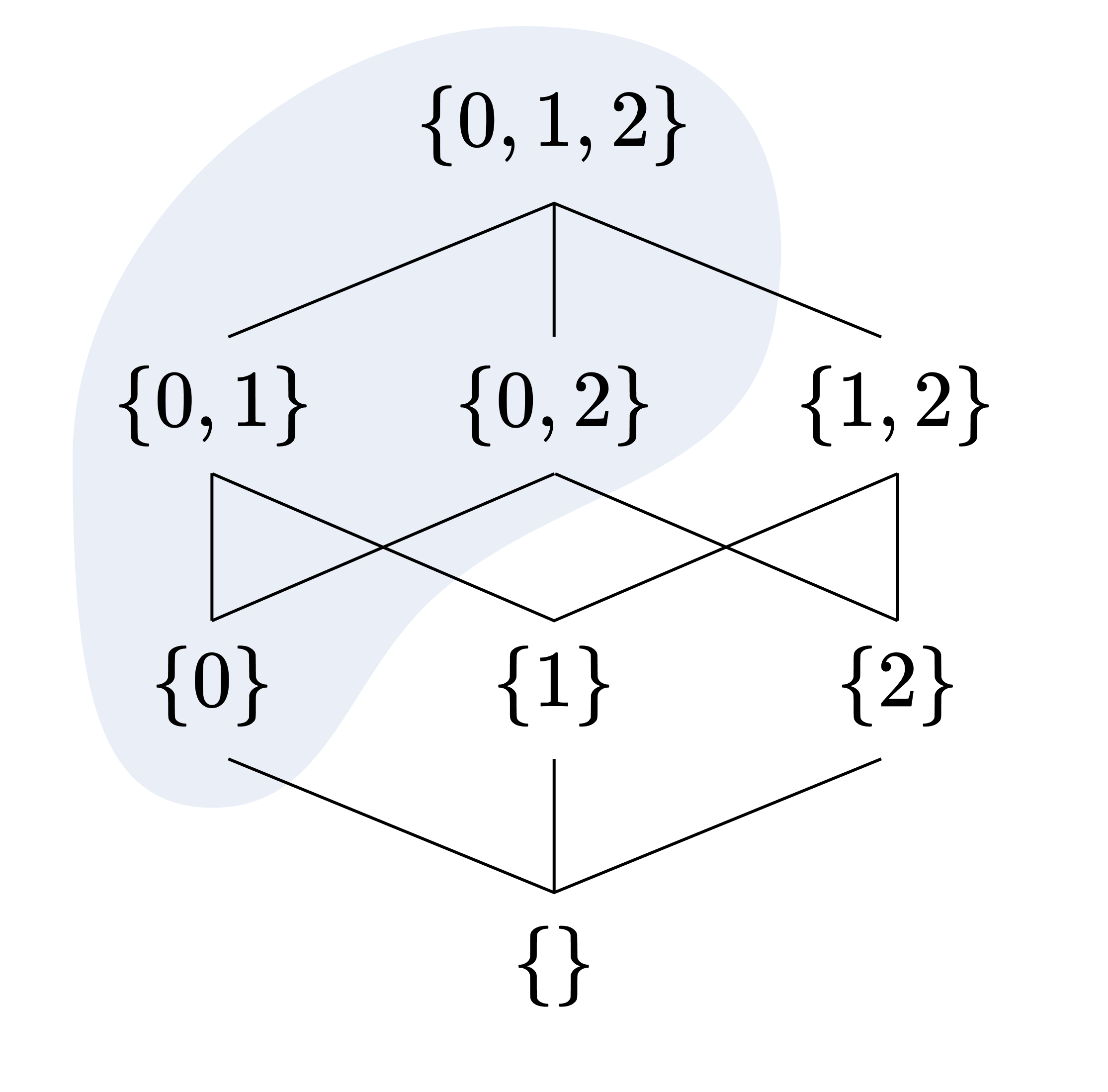

Filters can be understood more intuitively through Hasse diagrams. The shaded region represents a filter on $X = \lbrace 0, 1, 2 \rbrace$. If we understand the Hasse diagram as representing a stream of water from $\varnothing$ to $X$, the region an ink dropped at a particular point spreads over forms a filter.

By axioms 2 and 4, if $A \in \mathcal{F}$, then $A^c := X \setminus A \notin \mathcal{F}$. Strengthening this fact by requiring that for every subset of $X$, either the set or its complement is in the filter, we obtain the definition of an ultrafilter.

Definition. A filter $\mathcal{F}$ on $X$ is an ultrafilter if it satisfies:

\[\forall A \in \mathcal{P}(X) : A \in \mathcal{F} \lor A^c \in \mathcal{F}\]

The filter in the previous diagram is an ultrafilter. Note that an ultrafilter occupies exactly half of the Hasse diagram.

3. Ultrafilters on Infinite Sets

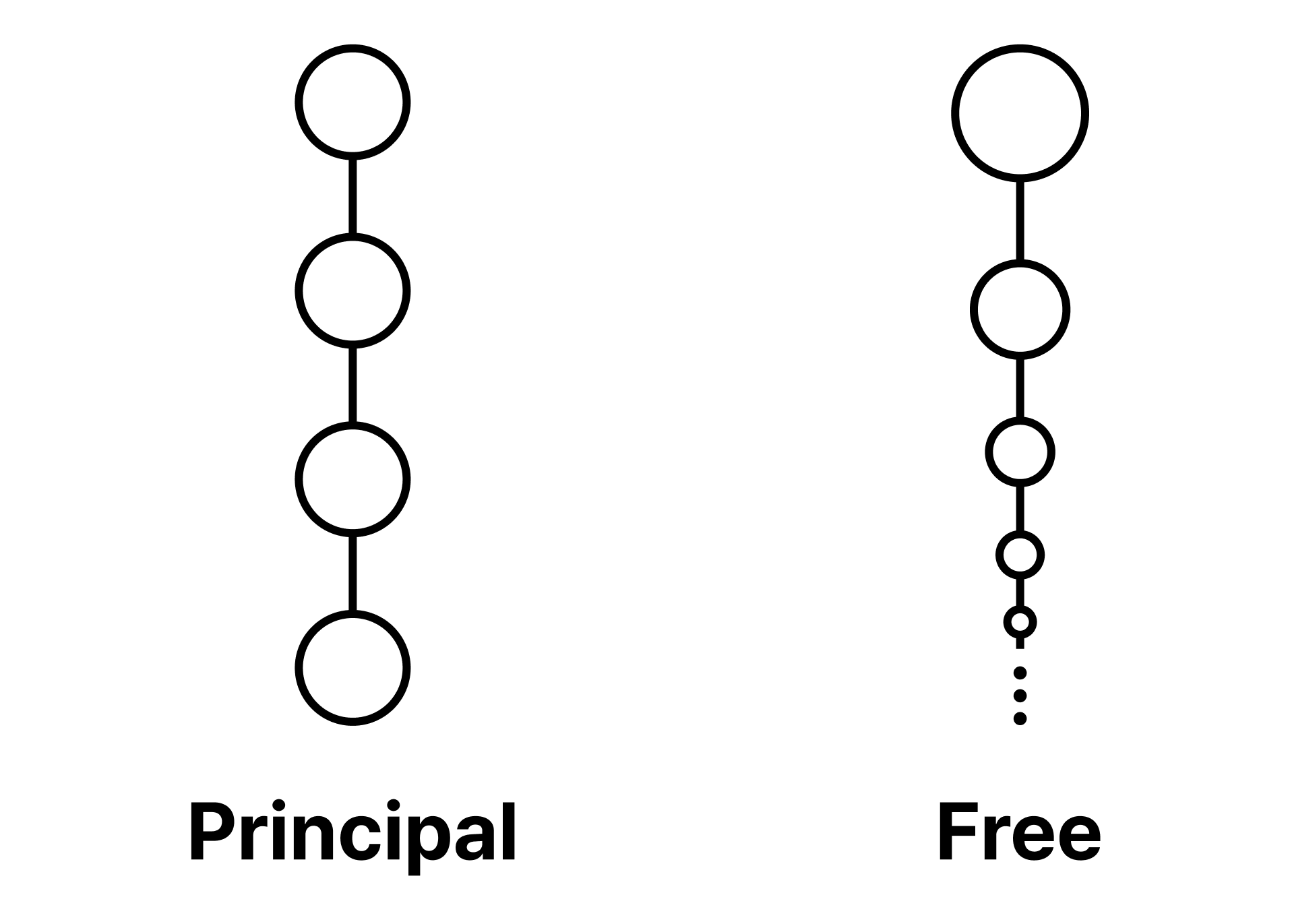

A filter with the least element is called a principal filter, while a filter that is not principal is called a free filter. All filters we have seen so far are principal filters, which perfectly match the image of “the region an ink dropped at a particular point spreads over”.

Exercise.

- Show that the least element of a principal filter is a singleton.

- Show that “a filter with a minimal element” is an equivalent definition of the principal filter.

Unlike principal filters, free filters are difficult to visualise intuitively, due to the following theorem:

Theorem. Every filter on a finite set is principal.

Proof. Suppose $A_0 \in \mathcal{F}$ is not a minimal element. Then there exists some $B \in \mathcal{F}$ such that $A_1 = A_0 \cap B \subsetneq A$. That is, $|A_1| < |A_0 |$. If $A_1$ is a minimal element, the proof is complete; otherwise, we repeat the same process. Since the given set has finite cardinality, this process cannot continue indefinitely and must terminate at a minimal element. ■

This theorem can also be understood as follows: a free filter is one that contains an infinitely descending chain of subsets within it. It thus does not reach a minimal element nor the empty set through finite intersections. Hence, only filters on infinite sets can be free.

Let us examine a concrete example.

Definition. Let $X$ be an infinite set. A subset $A \subset X$ is cofinite if $X \setminus A$ is finite.

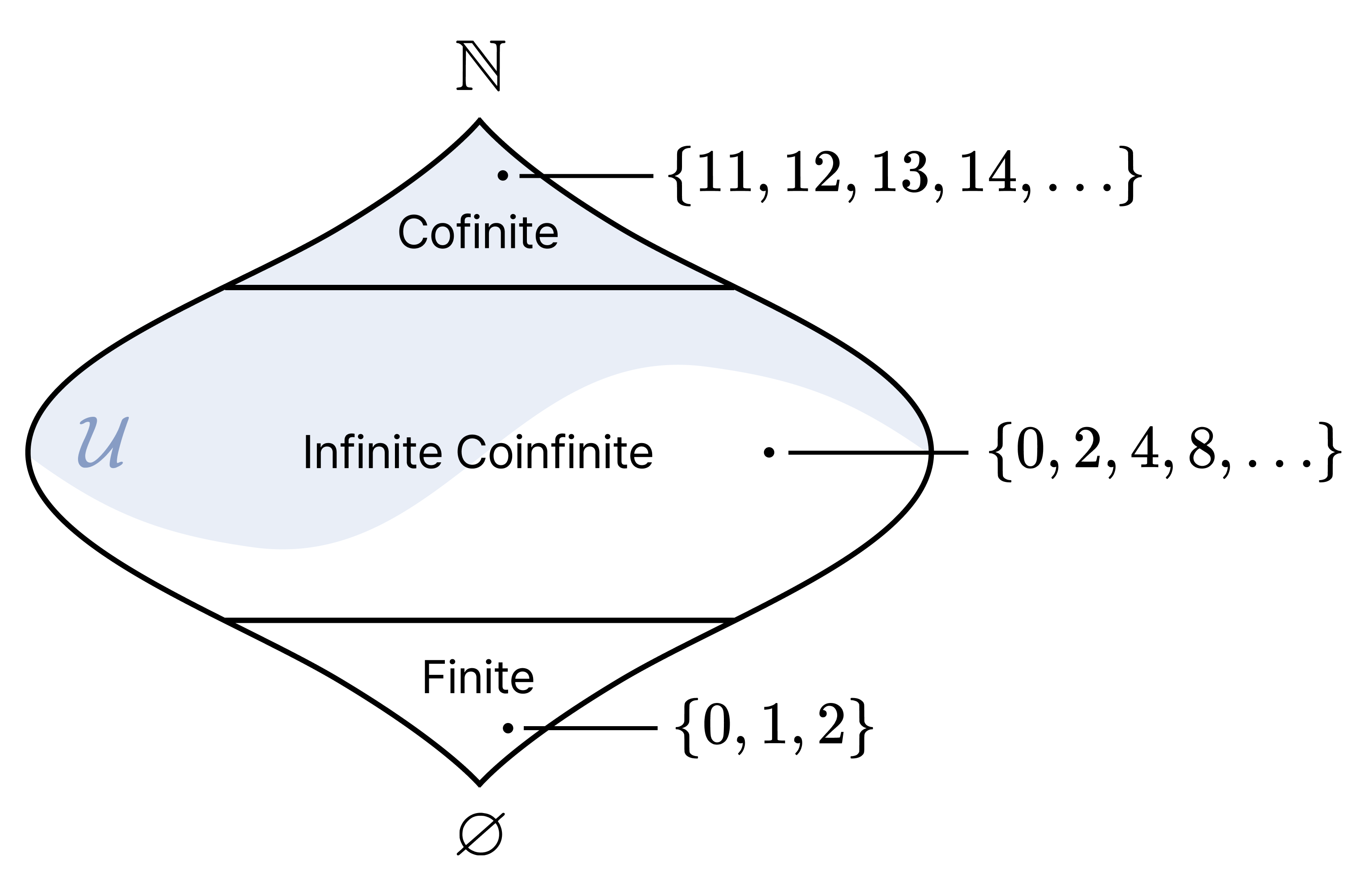

Theorem. Let $\mathcal{F}$ be the collection of all cofinite subsets of $\mathbb{N}$. Then $\mathcal{F}$ is a free filter.

The proof is left as an exercise. The $\mathcal{F}$ in the above theorem is called the Fréchet filter. For instance, the set of numbers greater than 10 is an element of $\mathcal{F}$, but the set of even numbers is not.

Fréchet filter is not an ultrafilter. However, it can be extended to an ultrafilter by the following theorem:

Theorem. Every filter can be extended to an ultrafilter.

Proof. Let $\Omega$ be the collection of all filters on $X$, ordered by inclusion. Under this ordering, the union of filters forming a chain is itself a filter, as can be shown without much difficulty. Therefore, by Zorn’s lemma, $\Omega$ has a maximal element $\mathcal{U}$. We now claim that $\mathcal{U}$ is an ultrafilter. Assuming otherwise, there exists some $A_0 \subset X$ such that $A_0, A_0^c \notin U$. Define $\mathcal{V}$ as follows:

\[\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{U} \cup \lbrace A \subset X : A_0 \subset A \rbrace \cup \lbrace A_0 \cap U : U \in \mathcal{U} \rbrace\]One can verify that $\mathcal{V}$ is a filter. This contradicts the maximality of $\mathcal{U}$. Therefore, $\mathcal{U}$ is an ultrafilter. ■

Hence, the set of natural numbers possesses a free ultrafilter extending from the Fréchet filter. Let us call this filter the Fréchet ultrafilter.

4. The Hypernaturals

To summarise our discussion thus far, free ultrafilters, including the Fréchet ultrafilter, possess the following properties:

- They contain all cofinite sets as elements.

- They do not contain finite sets as elements.

- For $A \subset \mathbb{N}$, either $A$ is an element of the filter or $A^c$ is an element of the filter.

These three properties make the Fréchet ultrafilter perfectly suited for resolving the ambiguity problem we encountered when outlining the basic idea of ultraproducts in the introduction. We can now define the hypernaturals as follows.

Let $\mathcal{U}$ be a free ultrafilter. Define the following equivalence relation on $\mathbb{N}^\omega$:

\[(n_0, n_1, n_2, \dots) \sim (m_0, m_1, m_2, \dots) \iff \lbrace i \in \mathbb{N} : n_i = m_i \rbrace \in \mathcal{U}\]It is not difficult to verify that this is indeed an equivalence relation. Therefore, we can take equivalence classes:

\[\mathbb{N}^* := \mathbb{N}^\omega/\sim\]We call $\mathbb{N}^*$ the hypernaturals. This reveals why the hypernaturals were written as $[n]$ in the introduction — a hypernatural number is an equivalence class. Indeed, it would have more accurate to write $[n]$ ans $[(n, n, n, \dots)]$, but let us allow ourselves some abuse of notation.

What remains now is to define operations and relations on the hypernaturals. Addition of hypernaturals is defined naturally as follows:

\[[(n_0, n_1, \dots)] + [(m_0, m_1, \dots)] = [(n_0 + m_0, n_1 + m_1, \dots)]\]There is one subtle issue here. Since hypernaturals are equivalence classes, we need to show that the above operation is well-defined regardless of which representative of an equivalence class we choose. That is, for

\[\begin{gather} (n_0, n_1, \dots), (n_0', n_1', \dots) \in [n]\\ (m_0, m_1, \dots), (m_0', m_1', \dots) \in [m], \end{gather}\]we need to show that

\[(n_0, n_1, \dots) + (m_0, m_1, \dots), (n_0', n_1', \dots) + (m_0', m_1', \dots) \in [n + m]\]Fortunately, this is not too difficult to establish and is left as an exercise.

Multiplication and successor can be defined similarly. Binary relations such as $<$ are defined as follows:

\[(n_0, n_1, n_2, \dots) < (m_0, m_1, m_2, \dots) \iff \lbrace i \in \mathbb{N} : n_i < m_i \rbrace \in \mathcal{U}\]This definition can be naturally generalised to ternary and quaternary relations.

We have thus defined the hypernaturals. In the next article, we shall examine various nonstandard features of the hypernaturals and Łoś’s theorem, which shows that despite such nonstandardness, the hypernaturals and natural numbers cannot be distinguished by first-order logic.