Stone-Čech Compactification

10 Jul 2025Definition. Let $\iota : X \to Y$ be an embedding. That is, $\iota$ is injective and a homeomorphism between $X$ and $\iota [X]$. $Y$ is said to be a compactification of $X$ if it is a compact space such that $\overline{\iota [X]} = Y$.

Remarks

-

Generally, compactification of $X$ is not unique, as $\overline{X}$ may vary depending on the background topology.

-

If $X$ and $Y$ are Hausdorff, then $Y$ is a compact Hausdorff space, hence normal, hence Tychonoff (completely regular). Since it is known that subspaces of Tychonoff spaces are Tychonoff, $X$ is also Tychonoff. Thus, spaces that can be compactified as Hausdorff spaces are Tychonoff.

-

The converse also holds. That is, Tychonoff spaces can be compactified as Hausdorff spaces. This is one of the implications of the Stone-Čech compactification discussed in this post.

For a locally compact Hausdorff space $X$, there exists a one-point compactification space $X^\ast$. (From this fact and the above remark, it follows that locally compact Hausdorff spaces are Tychonoff.) In particular, $X^\ast$ is the “smallest” compactification of $X$.

The Stone-Čech compactification is, in some sense, the opposite concept. The Stone-Čech compactification space $\beta X$ of $X$ is the “largest” compactification of $X$. The precise definition of “largest” is given by the following universal property.

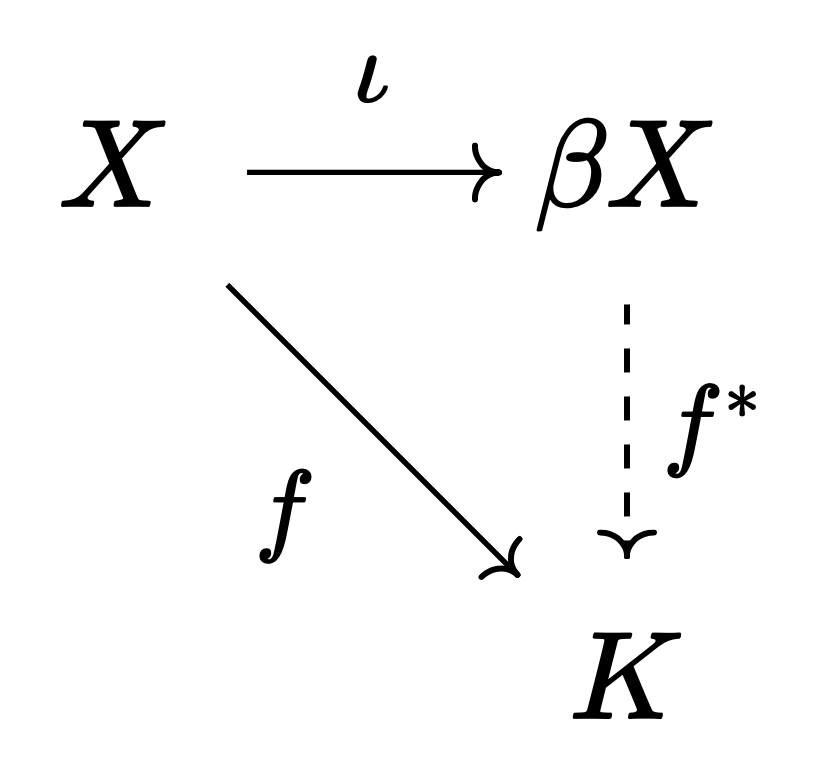

Theorem 1. If $X$ is Tychonoff, then there exists a unique compact Hausdorff space $\beta X$ and an embedding $\iota: X \to \beta X$ such that the following holds: for any compact Hausdorff space $K$ and any continuous map $f: X \to K$, there exists a unique continuous map $f^\ast: \beta X \to K$ such that $f = f^\ast \circ \iota$.

Furthermore, $\beta X = \overline{\iota[X]}$ and hence is a compactification of $X$. This is referred to as the Stone-Čech compactification.

Here, even without the condition that $X$ is Tychonoff, quite strong conclusions can still be maintained.

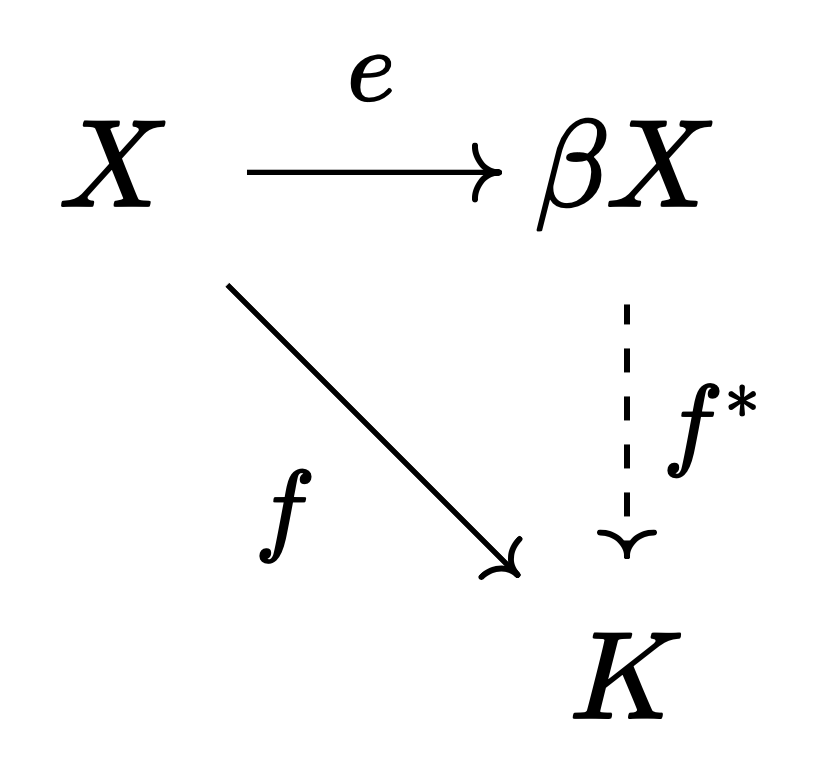

Theorem 2. If $X$ is a general topological space, then there exists a unique compact Hausdorff space $\beta X$ and a continuous function $e : X \to \beta X$ such that the following holds: for any compact Hausdorff space $K$ and any continuous map $f: X \to K$, there exists a unique continuous map $f^\ast: \beta X \to K$ such that $f = f^\ast \circ e$.

Furthermore, $\beta X = \overline{\iota[X]}$.

The difference is that $e$ is just a continuous function rather than an embedding. In fact, when $X$ is a general topological space, $e$ may not even be injective, let alone an homoemorphism. In this case, $\beta X$ is not a compactification of $X$ in the strict sense, but for convenience, this post will generally refer to $\beta X$ as the Stone-Čech compactification of $X$.

Unlike one-point compactifications, which are only possible for locally compact spaces, the Stone-Čech compactification is possible for all topological spaces. Consequently, the Stone-Čech compactification can be regarded as a functor that maps the category of general topological spaces $\mathbf{Top}$ to the category of compact Hausdorff spaces $\mathbf{CHaus}$. Indeed, the following holds.

Theorem 3. The forgetful functor $U: \mathbf{CHaus} \to \mathbf{Top}$ has a left adjoint $\beta: \mathbf{Top} \to \mathbf{CHaus}$.

Due to the equivalence discussed in a previous post, this may well be taken as the definition of Stone-Čech compactification.

The proof of Theorem 3 consists of three main steps. First, we define $\beta X$ for a topological space $X$. Second, we show that $\beta X$ satisfies the universal property. Third, we show that the relationship between $X$ and $\beta X$ is functorial, meaning that $\beta$ is a functor. Although Theorems 1, 2, and 3 are distinguished above, the proof below will demonstrate all three theorems together.

Proof.

1. Defining $\beta X$

Let us define the set $C$ as follows.

\[C = \{ f \mid f : X \to [0, 1] \text{ is continuous } \}\]We shall give the product topology to $[0, 1]^C$ to form a topological space. $[0, 1]^C$ can be thought of as the space of maps from $C$ to $[0, 1]$. Note that the product of Hausdorff spaces is always Hausdorff, and the product of compact spaces is always compact (Tychonoff’s theorem), so $[0, 1]^C$ is a compact Hausdorff space. Now, let us define $e: X \to [0, 1]^C$ as follows.

\[e: x \mapsto \lambda_x \quad \text{where} \quad \lambda_x : f \mapsto f(x)\]By the properties of the product topology (indeed, its definition), $e$ is a continuous function. In particular, if $X$ is a Tychonoff space, then by the Urysohn lemma and its corollary (the theorems in this post), $e$ is an embedding.

Let us define $\beta X$ as the closure of $e[X]$ in $[0, 1]^C$. Since $\beta X$ is a closed subset of a compact space, it is compact, and since it is a subspace of a Hausdorff space, it is Hausdorff. Therefore, $\beta X$ is compact Hausdorff. In particular, due to the remark in the previous paragraph, if $X$ is Tychonoff, then $\beta X$ is a compactification of $X$.

2. $\beta X$ satisfies the universal property

Now let us show that $\beta X$ satisfies the universal property. First, we consider the case when $K = [0, 1]$.

Let us assume we are given a continuous map $f: X \to [0, 1]$. We define $f^\ast : \beta X \to [0, 1]$ as follows.

\[f^\ast : \lambda \mapsto \lambda (f)\]That is, for the projection map $\pi_f: [0, 1]^C \to [0, 1]$ that maps $(x_g)_{g \in C}$ to $x_f$, we have $f^\ast = \pi_f \rvert_{\beta X}$. Since $\pi_f$ is continuous, $f^\ast$ is continuous. Furthermore, for any $x \in X$,

\[(f^\ast \circ e)(x) = f^\ast (\lambda_x) = \lambda_x(f) = f(x)\]Thus, $f^\ast$ is the map required by the universal property.

For general $K$ compact Hausdorff and $f: X \to K$ continuous, we observe that $K$ is Tychonoff, and hence can be embedded into $[0, 1]^J$ for some index set $J$. It then follows that without loss of generality we may only consider cases where $K = [0, 1]^J$ and $f: X \to [0, 1]^J$. In such cases, we let $f^\ast$ be:

\[f^\ast : \lambda \mapsto (\lambda (\pi_\alpha f))_{\alpha \in J}\]It follows from the $K = [0, 1]$ case that $f^\ast$ is continuous, and satisfies the universal property. Therefore, $\beta X$ is the Stone-Čech compactification of $X$.

3. $\beta$ is a functor

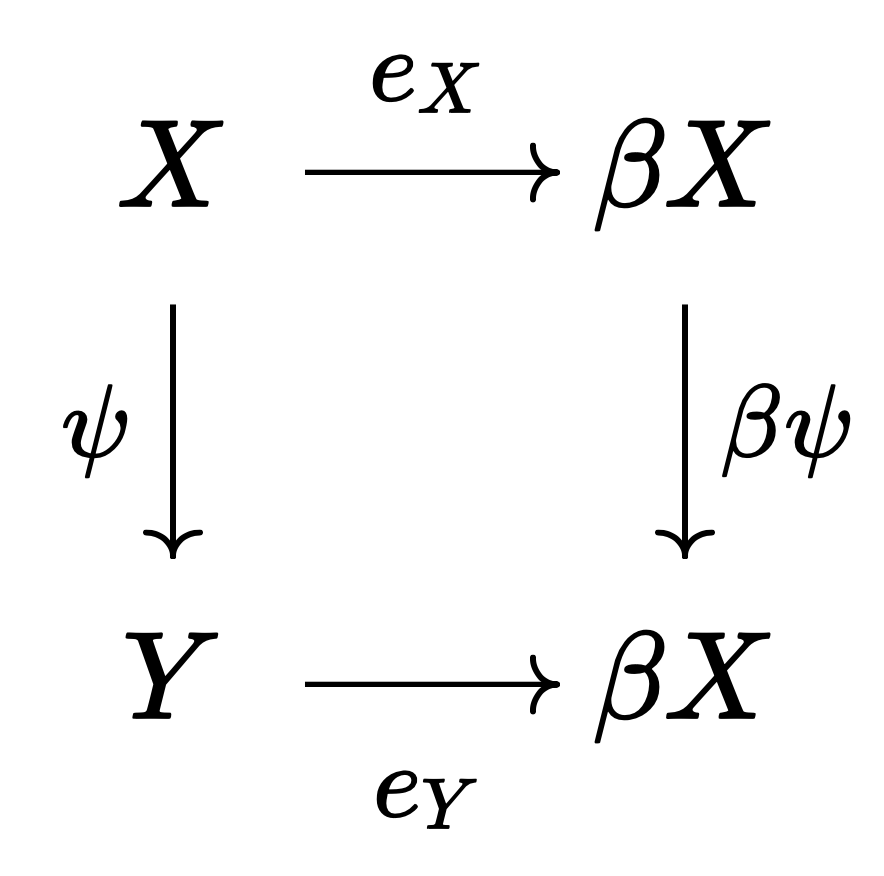

Finally, we need to show that $\beta$ is a functor. That is, we need to show that for any topological spaces $X, Y$ and continuous map $\psi : X \to Y$, one can define $\beta \psi$ such that the following commutative diagram holds.

Let us define $\beta \psi$ as follows. For any $\lambda \in \beta X$,

\[\beta \psi : \lambda \mapsto (g \mapsto \lambda(g \circ \psi) )_{g \in C_Y}\]where $C_Y$ is the collection of continuous functions $g : Y \to [0, 1]$. (Exercise: Verify that the above definition is well-defined by checking the domains and codomains of each function.) The commutativity of the diagram reduces to the following equation.

\[\beta \psi(\lambda_x) = \lambda_{\psi(x)}\]Expanding the left-hand side according to the definition, we see that the equation indeed holds.

\[\begin{align*} \beta \psi(\lambda_x) &= (g \mapsto \lambda_x(g\circ \psi))_{g \in C_Y} \\ &= (g \mapsto (g \circ \psi)(x))_{g \in C_Y} \\ &= (g \mapsto g(\psi(x)))_{g \in C_Y} \\ &= \lambda_{\psi(x)} \end{align*}\]Thus, $\beta : \mathbf{Top} \to \mathbf{CHaus}$ is a functor, and in particular, it is the left adjoint to $U: \mathbf{CHaus} \to \mathbf{Top}$. It follows that for any $X$, the pair $(e, \beta X)$ that satisfies the universal condition is the initial object in the comma category $(A \Rightarrow U)$, which implies uniqueness up to isomorphism. (For further details, refer to this post) ■