Are Mathematics and Ethics in the Same Boat?: The Evolutionary Challenge

07 Nov 2025This post was originally written in Korean, and has been machine translated into English. It may contain minor errors or unnatural expressions. Proofreading will be done in the near future.

This article summarises Justin Clarke-Doane’s Morality and Mathematics: The Evolutionary Challenge (2012). “The author” refers to the author of the paper, while “the writer” refers to the author of this post. To avoid confusion between “morality” and “ethics,” the term “ethics” is used consistently throughout.

Overview

One of the objections to ethical realism is the evolutionary challenge. According to this argument, the ethical beliefs held by modern humans were shaped by evolutionary pressures. However, the principles of evolution are independent of ethical facts, meaning that even in a counterfactual world with entirely different ethical facts, humans would have evolved to hold the same ethical beliefs. Therefore, if our ethical beliefs are true, it would be an extraordinary coincidence that they align with the outcomes of evolution. Proponents of the evolutionary challenge argue that ethical realists must either accept this extraordinary coincidence or concede that we have no grounds to believe our ethical beliefs are true.

For instance, the reason we hold the ethical belief “we should care for others” is likely because, in human evolution, groups that valued mutual cooperation had higher survival rates than those that prioritised selfishness. However, the fact that mutual cooperation increases survival rates is not an ethical fact but a game-theoretic or mathematical fact. Thus, even if selfishness were ethically superior to mutual cooperation, we would still have evolved to believe “we should care for others.”

On the other hand, the evolutionary challenge has traditionally been seen as not threatening mathematical realism. This is because the principles of evolution appear to depend on mathematical truths. For example, individuals who believe that 1 + 1 = 2 are more likely to survive than those who do not, precisely because 1 + 1 = 2 is actually true. Joyce explains this as follows:

Suppose there is one lion behind bush A and another lion behind bush B. Our ancestors, P and Q, are hiding behind bush C. P believes that one lion plus another lion equals two lions, while Q believes that one lion plus another lion equals zero lions. P is less likely to die and more likely to pass on their genes than Q. This is because P is less likely than Q to step out from behind bush C and be eaten by the two lions. However, the explanation for this fact [italicised fact] presupposes that one lion plus another lion is actually two lions and not zero lions.

However, the author of the paper argues that this reasoning is mistaken. They claim that the evolutionary challenge threatens mathematical realism to the same extent that it threatens ethical realism. Ultimately, the author asserts that accepting either ethical realism or mathematical realism while rejecting the other is an incoherent position.

1. What Exactly Is Realism?

Before delving into the argument, the author seeks to clarify what is meant by ethical realism and mathematical realism. Generally, the author defines D-realism for a domain of discourse D as the conjunction of the following four positions:

- D-Truth-Aptness. Sentences in D have truth values.

- D-Truth. Some atomic or existentially quantified sentences in D are true.

- D-Independence. The truth values of sentences in D are independent of minds and language in a meaningful sense.

- D-Literalness. Sentences in D should be taken literally.

When D is set to ethics, (1) rules out Ayer’s emotivism, (2) rules out Mackie’s error theory, (3) rules out constructivism, and (4) rules out Harman’s relativism. When D is set to mathematics, (1) rules out Hilbert’s formalism, (2) rules out Field’s fictionalism, (3) rules out Brouwer’s constructivism, and (4) rules out if-thenism.

This paper assumes both ethical realism and mathematical realism and examines whether they can withstand the evolutionary challenge. Additionally, it assumes that most of our ethical and mathematical beliefs are true.

2. The Evolutionary Challenge to Ethical Realism

Having clarified the requirements of realism, let us examine how the evolutionary challenge attacks ethical realism. The challenge is based on the following premise:

Strong Premise. Our ethical beliefs were shaped by evolutionary pressures that are independent of their truth.

The strong premise consists of the following two sub-premises:

E. Our ethical beliefs were shaped by evolution.

NTT. The evolution of ethical beliefs occurred in a non-truth-tracking manner.

The precise meaning of NTT is captured by the following counterfactual conditional:

P. Suppose all other facts remained the same, but ethical facts were entirely different. Even so, we would have evolved to hold the same ethical beliefs that are true in the actual world.

Some might argue that Q could serve as an alternative interpretation of NTT:

Q. We could have evolved to hold false ethical beliefs.

However, the author contends that Q is untenable. While Darwin noted that if humans had evolved in an environment like that of bees, they might have condoned the killing of brothers by unmarried females, this example does not substantiate Q. To substantiate Q, one would need the additional assumption that “in a bee-like environment, it would have been wrong for unmarried females to kill their brothers,” which is not self-evident. (Consider the differing ethical weight of infanticide in premodern societies with frequent famine versus modern societies.) Thus, the author argues that Q can only be substantiated by presenting cases where individuals hold fundamentally false ethical beliefs, such as “pain is good” or “pleasure is bad.” However, individuals who believe that pain is good and pleasure is bad would have been evolutionarily eliminated, making Q untenable. Therefore, P is the correct interpretation of NTT.

However, P also faces challenges. Many ethical realists argue that ethical properties are metaphysically necessarily identical to descriptive properties. For instance, if “pleasure is good” is true, this truth is metaphysically necessary. According to this view, it is metaphysically impossible for descriptive facts to remain fixed while ethical facts change. Thus, the following interpretation of P is untenable:

P1. In a metaphysical sense, suppose all other facts remained the same, but ethical facts were entirely different. Even so, we would have evolved to hold the same ethical beliefs that are true in the actual world.

Instead, the author argues that P should be understood as follows:

P2. Suppose all other facts remained the same, but ethical facts were entirely different. We can intelligibly imagine such a scenario. Even so, we would have evolved to hold the same ethical beliefs that are true in the actual world.

To illustrate, consider a child who guesses the answer to the problem of finding $\zeta(-1)$ as $-1/12$ and gets it right. Since $\zeta(-1) = -1/12$ is metaphysically necessary, the counterfactual statement “even if the answer to this problem were different, the child would still have guessed correctly (the child’s answer was truth-tracking)” is metaphysically vacuous. Nevertheless, we can imagine a scenario where $\zeta(-1) \neq -1/12$, and in such an imagined scenario, the child would have been wrong. In this sense, the child’s answer was non-truth-tracking.

With the meanings of E and NTT clarified, let us examine how the strong premise leads to a refutation of ethical realism. Street and others present the following argument:

- Even if it is metaphysically impossible for ethical facts to be entirely different, we can imagine such a scenario.

- As far as we can imagine, even if ethical facts were entirely different, the ethical beliefs shaped by evolution would remain the same.

- Therefore, the fact that we hold true ethical beliefs in the actual world is an unexplained coincidence.

However, the author argues that (2) does not necessarily lead to (3). To derive (3) from (2), the following general principle must be assumed:

If the fundamental facts of D were different, then the truth of the D-beliefs that remain unchanged is coincidental.

The author provides the following counterexample to this principle. Chulsoo sees a basketball flying towards him and believes, “a basketball is flying towards me.” Here, it is metaphysically necessary that a basketball is identical to atoms arranged basketballwise. However, we can imagine a world where matter is composed of something other than atoms. Even in such a world, if a basketball were flying towards Chulsoo, he would hold the same belief, “a basketball is flying towards me.” Thus, even if the fundamental facts about basketballs were different, Chulsoo would hold the same belief, yet the truth of his belief in the actual world is not coincidental.

Writer’s note: I believe the author has provided a flawed analogy. The belief “a basketball is flying towards me” held by Chulsoo in a world where basketballs are composed of atoms is not the same as the belief held by Chulsoo in a world where basketballs are composed of continua. This is because the meaning of “basketball” for the two Chulsoos is determined by ostension. In the former case, “basketball” refers to “atoms arranged basketballwise,” while in the latter, it refers to “continua condensed basketballwise.” Thus, if the fundamental facts about basketballs change, Chulsoo would hold a different belief. In contrast, the meaning of ethical language does not seem to be determined by ostension.

Nevertheless, the author argues that even if Street’s argument does not demonstrate the complete impossibility of explaining why we hold true ethical beliefs, it at least shows that the following two explanations are flawed:

- Evolutionary Explanation. We hold true ethical beliefs because we were selected to hold true ethical beliefs.

- Trivial Explanation. We hold true ethical beliefs because the current ethical facts are the only possible ethical facts, and believing those facts is evolutionarily advantageous.

Focus on the distinction between the evolutionary explanation and the trivial explanation. The evolutionary explanation claims that if ethical facts had changed — even if only in an imaginable sense — we would have evolved to believe those changed facts. In contrast, the trivial explanation asserts that it is impossible for ethical facts to change, either metaphysically or imaginably, and therefore, it suffices to explain how evolution produced beings that believe the actual ethical facts.

Writer’s note: The trivial explanation seems to presuppose the game-theoretic explanation mentioned in the overview. That is, the trivial explanation attempts to overcome the evolutionary challenge to ethical realism by relying on (i) the strong necessity of ethical facts, (ii) the mathematical fact that those ethical facts are evolutionarily advantageous, and (iii) the necessity of mathematical facts. This appears to ground the explanation of the truth of ethical beliefs in the explanation of the truth of mathematical beliefs.

However, if the purpose of the evolutionary challenge is to argue that the evolutionary explanation and the trivial explanation are flawed, then the challenge does not need to assume E ∧ NTT but only E → NTT. Thus, the evolutionary challenge can be summarised as follows:

Evolutionary Challenge. If E → NTT, then explaining why we hold true ethical beliefs through the evolutionary explanation or the trivial explanation is flawed.

The author summarises the evolutionary challenge in this way and then examines how valid it is in the context of mathematics.

3. Does Mathematics Influence Evolution?

It is commonly thought that mathematics is not subject to the evolutionary challenge. Unlike ethical truths, which are independent of evolution (ethical truths can change without affecting evolution), mathematical truths are thought to influence evolution. Let us revisit Joyce’s example:

Suppose there is one lion behind bush A and another lion behind bush B. Our ancestors, P and Q, are hiding behind bush C. P believes that one lion plus another lion equals two lions, while Q believes that one lion plus another lion equals zero lions. P is less likely to die and more likely to pass on their genes than Q. This is because P is less likely than Q to step out from behind bush C and be eaten by the two lions. However, the explanation for this fact [italicised fact] presupposes that one lion plus another lion is actually two lions and not zero lions.

However, the author identifies two problems with Joyce’s argument. The first problem arises from the principle underlying Joyce’s argument:

If the evolutionary explanation for why we hold certain beliefs about D presupposes the content of those beliefs, then we were selected to hold true beliefs about D.

The author argues that even if we were not selected to hold true D-beliefs (i.e., our D-beliefs are false or non-truth-tracking), the evolutionary explanation for our D-beliefs can still presuppose the content of those beliefs. For instance, all types of explanations presuppose the content of our logical beliefs, yet it remains questionable whether we were selected to hold true logical beliefs (see the writer’s short paper).

Even so, one might counter by adopting Quine-Putnam-style holistic epistemology, arguing that the consideration that mathematical facts explain our mathematical beliefs can serve as a provisional justification for the truth of those mathematical facts. In response, the author identifies a second, more serious problem: the evolutionary explanation for our mathematical beliefs is not actually related to mathematical facts. Instead, the author argues that the evolutionary explanation is only related to first-order logical facts. In the earlier example of the lions, the reason P is more likely to survive than Q is not because M is true but because L is true:

M. 1 + 1 = 2

L. If there is one lion behind bush A, one lion behind bush B, and no lion behind bush A is the same as any lion behind bush B, then there are two lions behind bushes A and B.

L can be expressed as the following first-order logical formula:

\[\begin{align} &\;\exists! x A(x) \land \exists! y B(y) \land \forall x, y (A(x) \land B(y) \rightarrow x \neq y) \\ &\rightarrow \exists x, y \big((x \neq y) \land (A(x) \lor B(x)) \land (A(y) \lor B(y)) \\ &\quad \quad \land\; \forall z ( (A(z) \lor B(z)) \rightarrow (z = x) \lor (z = y))\big) \end{align}\]While many mathematicians and philosophers hold that mathematics can be reduced to logic, no one claims that the reduction ends at first-order logic. Therefore, if the evolutionary explanation for our mathematical beliefs depends only on first-order logical facts and not on mathematical facts, it cannot definitively or provisionally conclude that we were selected to hold true mathematical beliefs.

Moreover, mathematical realists cannot simply identify M with L. This is because one of the requirements of realism is D-literalness. The statement 1 + 1 = 2 must be taken literally, and when taken literally, it asserts the existence of the numbers 1 and 2 and a specific relationship between them under addition.

In conclusion, the reason P is more likely to survive than Q is not because the content of P’s mathematical belief M is true but because the corresponding logical content L is true. The correspondence between M and L can be explained without assuming mathematical objects. Various anti-realist positions mentioned earlier — formalism, fictionalism, constructivism, if-thenism — all explain the correspondence between M and L without positing mathematical entities.

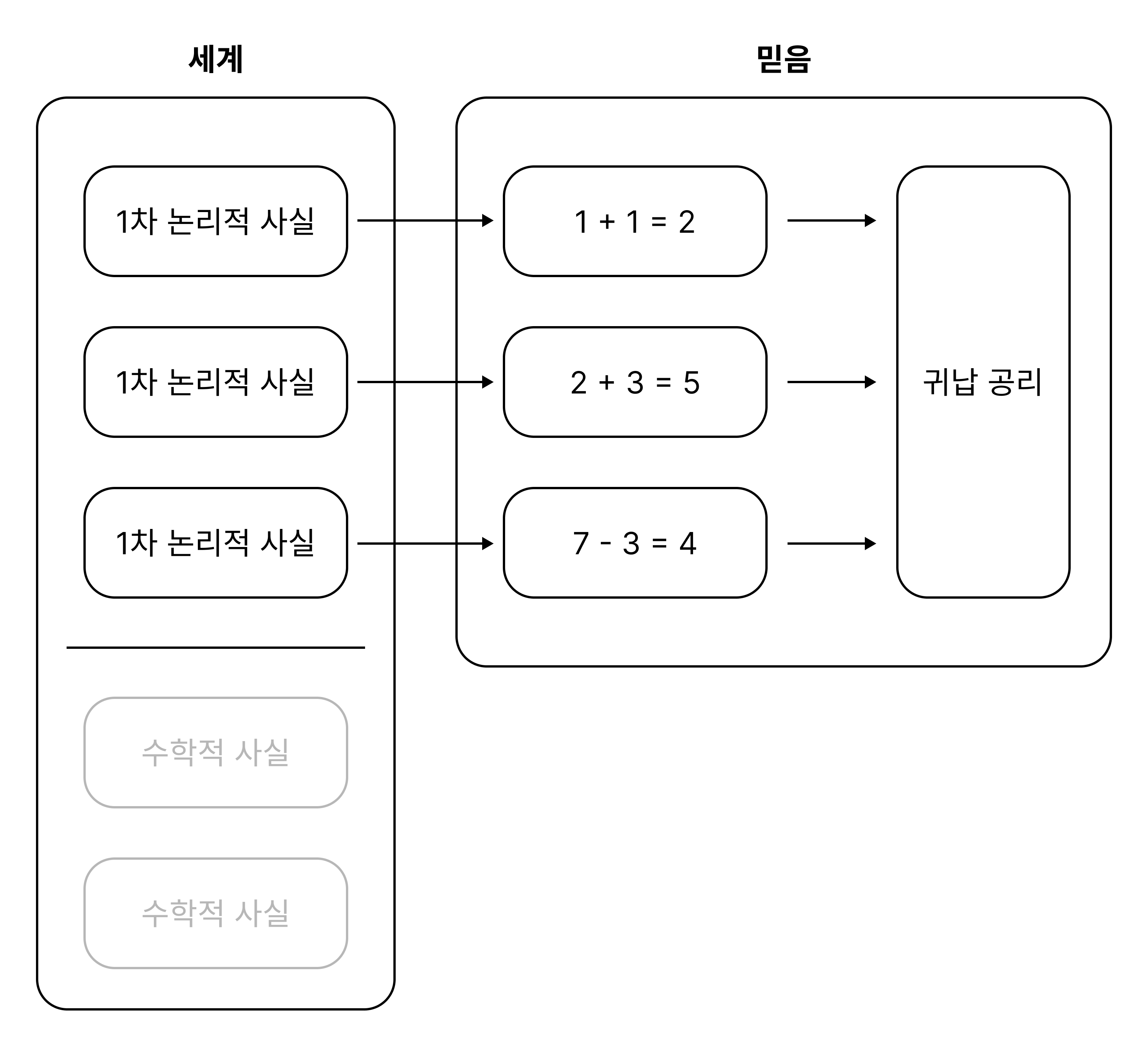

Of course, we also hold mathematical beliefs that cannot be captured by first-order logic. Belief in the induction axiom is one example. However, the author points out that belief in the induction axiom was not directly shaped by evolutionary pressures. The induction axiom was not explicitly formulated until the 17th century. Belief in the induction axiom arose from formalising basic arithmetic beliefs. In other words, we believe in the induction axiom because of our beliefs in basic arithmetic, which were shaped by first-order logical facts, not mathematical facts. Consequently, mathematical facts that transcend logic have no influence on the evolutionary formation of mathematical beliefs (see the following diagram: A → B means “A causes the evolution of beings that believe B”).

Here, the author briefly raises the following question: does the preceding discussion show that we were selected to hold true first-order logical beliefs? The author thinks the answer is “no.” This is because logical facts become exceedingly complex even for simple arithmetic facts like 5 + 7 = 12. Evolutionarily, it seems more advantageous for beings to simply hold mathematical beliefs than to hold mathematical beliefs, logical beliefs, and beliefs about how to translate each mathematical statement into a logical statement. Thus, while logical facts might influence the evolution of our mathematical beliefs, it remains unclear how they influenced the evolution of our logical beliefs (— or so the author seems to think, though their comments on this point are too terse to be clear. For a separate argument on why the formation of logical beliefs cannot be explained evolutionarily, see the writer’s short paper).

4. Is Another Mathematics Imaginable?

Having dismissed the evolutionary explanation for mathematics, the author turns to the trivial explanation. The trivial explanation asserts that the current mathematical facts are the only possible mathematical facts.

It is commonly thought that the trivial explanation is unconvincing in ethics. This is because, in ethics, sufficiently reasonable individuals often hold conflicting positions. If rational individuals can hold different ethical facts, then worlds with different ethical facts are imaginably coherent. In contrast, such conflicts are rarely observed in mathematics. Compare the divergence of opinions on the trolley dilemma with the consensus on the Pythagorean theorem.

However, the author argues that this comparison is biased against ethical realists. We can find ethical propositions on which ethical realists unanimously agree — for instance, “it is wrong to torture children for fun.” Conversely, we can also find mathematical axioms on which mathematical realists disagree. Finitism denies the axiom that there is always a natural number greater than any given natural number, the