Euler-Poincaré Theorem

23 Nov 2025This post was originally written in Korean, and has been machine translated into English. It may contain minor errors or unnatural expressions. Proofreading will be done in the near future.

Readers may recall learning the following theorem in their youth:

Euler’s Formula. For a convex polyhedron, let $v, e, f$ denote the number of vertices, edges, and faces, respectively. Then $v - e + f = 2$.

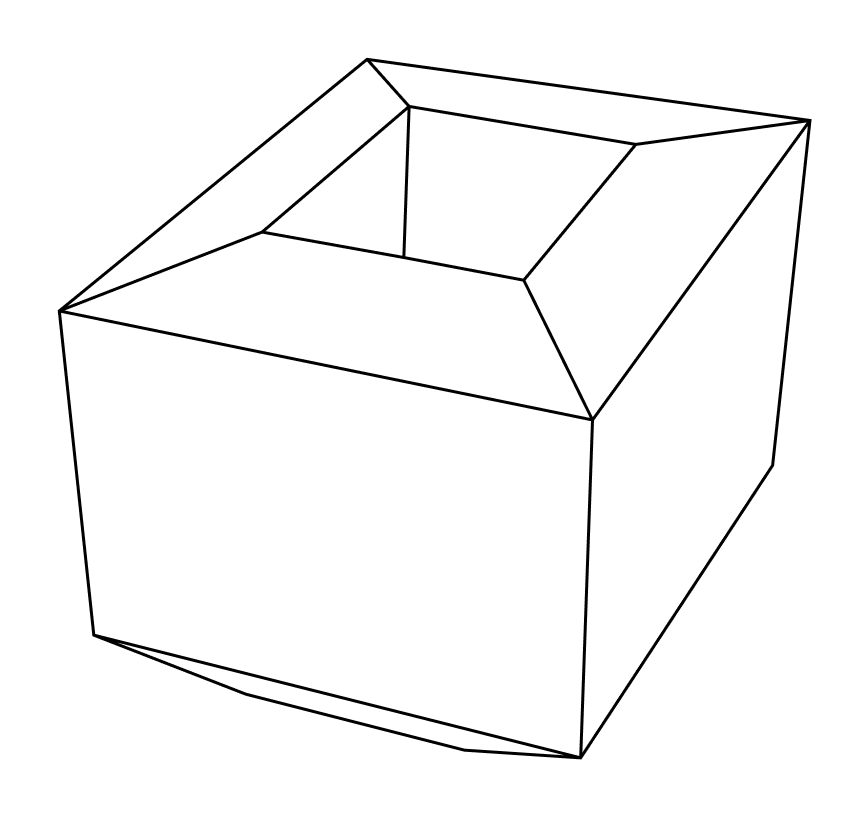

For instance, in the case of a cube, $v = 8, e = 12, f = 6$, so $v - e + f = 2$ holds. The condition of convexity is crucial; if the polyhedron has “holes,” the formula does not hold. For example, in the case of the punctured prism below, $v = 16, e = 32, f = 16$, so $v - e + f = 0$.

From this, we may conjecture that the value of $v - e + f$ is determined by the topology of the shape. This is the essence of the Euler-Poincaré theorem. Before stating the theorem, let us first define the following concept:

Definition. For a topological space $X$, the rank of the free part of the homology group $H_p(X)$ of $X$ is called the $p$th Betti number of $X$, denoted $R_p(X)$.

While it is customary to denote this as $b_p(X)$, we adopt a different notation here as $b_p$ will be used for another purpose in this article. Since homology groups are topological invariants, Betti numbers are also topological invariants.

For example, the homology groups of a torus are as follows:

- $H_0(X) = \mathbb{Z}$

- $H_1(X) = \mathbb{Z} \oplus \mathbb{Z}$

- $H_2(X) = \mathbb{Z}$

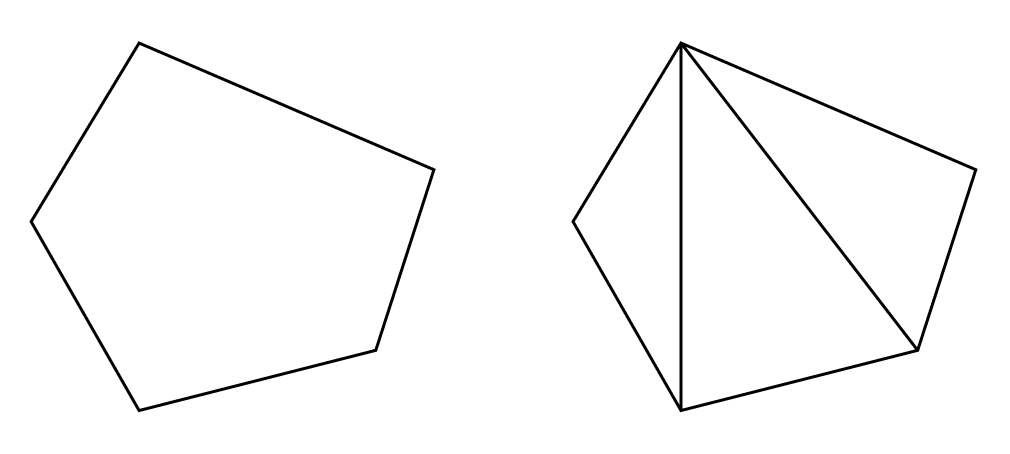

Thus, the 0th, 1st, and 2nd Betti numbers of the torus are 1, 2, and 1, respectively. Intuitively, Betti numbers represent the number of “holes” (see previous post). In particular, the 0th Betti number corresponds to the number of connected components of $K$. For instance, if two tetrahedra are considered as a single simplicial complex, the 0th Betti number of this complex is 2.

Euler-Poincaré Theorem. For an $n$-dimensional simplicial complex $K$, let $\alpha_p \; (p \leq n)$ denote the number of $p$-simplices in $K$. Then the following holds:

\[\sum^n_{p = 0} (-1)^p\alpha_p = \sum^n_{p=0}(-1)^p R_p(K)\]

In proving this theorem, it is more natural to view $p$-chains as elements of a vector space rather than a free group, and we adopt this approach.

Proof. Let $C_p, Z_p, B_p$ denote the vector spaces of $p$-chains, cycles, and boundaries of $K$ over the field of rational numbers, respectively. Let $\lbrace d^i_p \rbrace $ be a maximal subset of $C_p$ that does not linearly generate cycles, and let the vector space spanned by $\lbrace d^i_p \rbrace $ be $D_p$. Then the following holds ($\oplus$ denotes the direct sum of vector spaces):

\[\begin{gather} C_p = D_p \oplus Z_p\\\\ \alpha_p = \dim C_p = \dim D_p + \dim Z_p \end{gather}\]For $p \leq n - 1$, let $b^i_p = \partial d^i_{p + 1}$. Let the vector space spanned by $\lbrace b^i_p \rbrace $ be $B_p$. Since $\partial$ is a linear operator, it follows from the fact that $\lbrace d^i_{p +1} \rbrace $ forms a basis of $D_{p + 1}$ that $\lbrace b^i_p \rbrace $ forms a basis of $B_p$. We prove the following lemma:

Lemma. $B_p$ contains all $p$-boundaries of $K$.

Proof. If $b_p$ is a $p$-boundary of $K$, then there exists some $c_{p + 1} \in C_{p + 1}$ such that $\partial c_{p + 1} = b_p$. By the relation $C_{p + 1} = D_{p + 1} \oplus Z_{p + 1}$, there exist unique $d_{p + 1} \in D_{p + 1}$ and $z_{p + 1} \in Z_{p + 1}$ such that $c_{p + 1 } = d_{p + 1} + z_{p + 1}$. Since $\partial z_{p + 1} = 0$, it follows that $\partial d_{p + 1} = b_p$. Hence, $b_p \in B_p$. □

Let $\lbrace z^i_p \rbrace $ be a maximal subset of $Z_p$ that does not linearly generate elements of $B_p$, and let the vector space spanned by $\lbrace z^i_p \rbrace $ be $G_p$. By the lemma, the following holds:

\[\dim G_p = R_p\]Thus, we have:

\[\begin{gather} Z_p = B_p \oplus G_p\\\\ \dim Z_p = \dim B_p + \dim G_p = \dim D_{p + 1} + R_p \end{gather}\]Combining this with earlier results, we obtain the following for $p \leq n - 1$:

\[\alpha_p = \dim D_{p + 1} + \dim D_p + R_p\]For $p = n$, $\alpha_n = \dim D_n + R_n$, and for $p = 0$, $\alpha_0 = \dim D_1 + R_0$. Hence, we derive the following (wlog, $n$ is even):

\[\begin{alignat}{3} &\alpha_n &&= \;\cancel{\dim D_n} + R_p \\ &-\alpha_{n-1} &&= \;\cancel{-\dim D_{n}} \cancel{- \dim D_{n - 1}} - R_{n - 1} \\ &\alpha_{n-2} &&= \;\cancel{\dim D_{n - 1}} \cancel{ + \dim D_{n - 2}} + R_{n - 2} \\ &&\vdots \\ &-\alpha_{1} &&= \;\cancel{-\dim D_{2}} \cancel{-\dim D_{1}} - R_{1} \\ &\alpha_{0} &&= \;\cancel{\dim D_{1}} + R_{0} \\ \hline &\sum_{p = 0}^n (-1)^p \alpha_p &&= \;\sum_{p=0}^n (-1)^p R_p(K) \quad \blacksquare \end{alignat}\]Definition. For a topological space $X$, the following value is called the Euler characteristic:

\[\xi(X) = \sum (-1)^p R_p(X)\]

Since Betti numbers are topological invariants, the Euler characteristic is also a topological invariant.

Corollary. Let $v, e, f$ denote the number of vertices, edges, and faces of a polyhedron $P$, respectively. Let $X$ denote the surface of $P$ as a 2-dimensional topological space. Then the following holds:

\[v - e + f = \xi(X)\]

Proof. The triangulation of a $k$-gon can be obtained by adding $k - 3$ edges, which creates $k - 3$ faces. Thus, $P$ has the same $v - e + f$ value as its triangulation, which equals the Euler characteristic. ■

Earlier, we observed that for a polyhedron with one hole, $v - e + f = 0$. Indeed, the 0th, 1st, and 2nd Betti numbers of a torus are 1, 2, and 1, respectively, and $1 - 2 + 1 = 0$. On the other hand, the homology groups of a sphere are as follows:

- $H_0(K) = \mathbb{Z}$

- $H_1(K) = 0$

- $H_2(K) = \mathbb{Z}$

Thus, the 0th, 1st, and 2nd Betti numbers of a sphere are 1, 0, and 1, respectively, and $1 - 0 + 1 = 2$. Therefore, for convex polyhedra, $v - e + f = 2$.