Ideals and Filters in Boolean Algebraic Structures

18 Jul 2025Boolean Algebra

Boolean algebra is an algebra consisting of logical operations such as $\lor, \land, \lnot$ defined over $0$ representing false and $1$ representing true.

| $a$ | $b$ | $a \lor b$ | $a \land b$ | $\lnot a$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $0$ | $0$ | $0$ | $0$ | $1$ |

| $0$ | $1$ | $1$ | $0$ | $1$ |

| $1$ | $0$ | $1$ | $0$ | $0$ |

| $1$ | $1$ | $1$ | $1$ | $0$ |

When we regard $0$ and $1$ not as formal symbols representing false and true, but as integers, we can check that $\lor$ corresponds to $\max$, $\land$ to $\min$, and $\lnot$ to the complement operation $\bar{(\cdot)}: 0 \mapsto 1, 1 \mapsto 0$.

| $a$ | $b$ | $\max (a, b)$ | $\min (a, b)$ | $\bar{a}$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $0$ | $0$ | $0$ | $0$ | $1$ |

| $0$ | $1$ | $1$ | $0$ | $1$ |

| $1$ | $0$ | $1$ | $0$ | $0$ |

| $1$ | $1$ | $1$ | $1$ | $0$ |

Building on this insight, we can naturally extend the domain of Boolean algebra from $\lbrace 0, 1 \rbrace$ to $[0, 1]$. For instance, $0.2 \lor 0.7 = 0.7$ and $0.3 \land \lnot(0.9) = 0.1$. Developing this idea further, we can define operations structurally similar to Boolean algebra on sets with appropriate order relations, and conversely, sets with operations structurally similar to Boolean algebra can be given appropriate order relations. This is the idea of Boolean algebraic structures.

Definition. When binary operations $\lor, \land$ and unary operation $\lnot$ defined on a set $A$ with two elements $0$ and $1$ satisfy the following axioms, we call $(A, 0, 1, \lor, \land, \lnot)$ a Boolean algebraic structure.

Axiom $\lor$ $\land$ Associativity $a \lor (b \lor c) = (a \lor b) \lor c$ $a \land (b \land c) = (a \land b) \land c$ Commutativity $a \lor b = b \lor a$ $a \land b = b \land a$ Distributivity $a \lor (b \land c) = (a \lor b) \land (a \lor c)$ $a \land (b \lor c) = (a \land b) \lor (a \land c)$ Identity $a \lor 0 = a$ $a \land 1 = a$ Complement $a \lor \lnot a = 1$ $a \land \lnot a = 0$ Absorption $a \lor (a \land b) = a$ $a \land (a \lor b) = a$

Remark.

-

The absorption law can be proved from the other five axioms.

-

The term “complement” is used instead of “inverse”, because while multiplying $x$ by its multiplicative inverse $x^{-1}$ should yield the multiplicative identity $1$, and adding the additive inverse $-x$ should yield the additive identity $0$, in Boolean algebraic structures the result of $x \lor \lnot x$ is not the disjunctive identity $0$ but rather the conjuctive identity $1$, and the result of $x \land \lnot x$ is not $1$ but rather $0$.

Verify that the two examples in the introduction are Boolean algebraic structures. As another example, consider the power set $\mathcal{P}(X)$ of the set $X = \lbrace p, q, r \rbrace $. Verify that $\mathcal{P}(X)$ becomes a Boolean algebraic structure when we define:

- $a \lor b = a \cup b$

- $a \land b = a \cap b$

- $\lnot a = X \setminus a$

- $1 = X$

- $0 = \varnothing$

Generally, when $X$ is any set, the power set of $X$ forms a Boolean algebraic structure.

A Boolean algebraic structure can be given a partial order in a natural way.

Theorem. Let $A$ be a Boolean algebraic structure. Define the following binary relation:

\[a \leq b \iff a = a \land b\]Then $\leq$ is a partial order on $A$. $1$ and $0$ are respectively the greatest and least elements of $\leq$. $\lor$ and $\land$ are respectively operations that yield the supremum and infimum with respect to $\leq$.

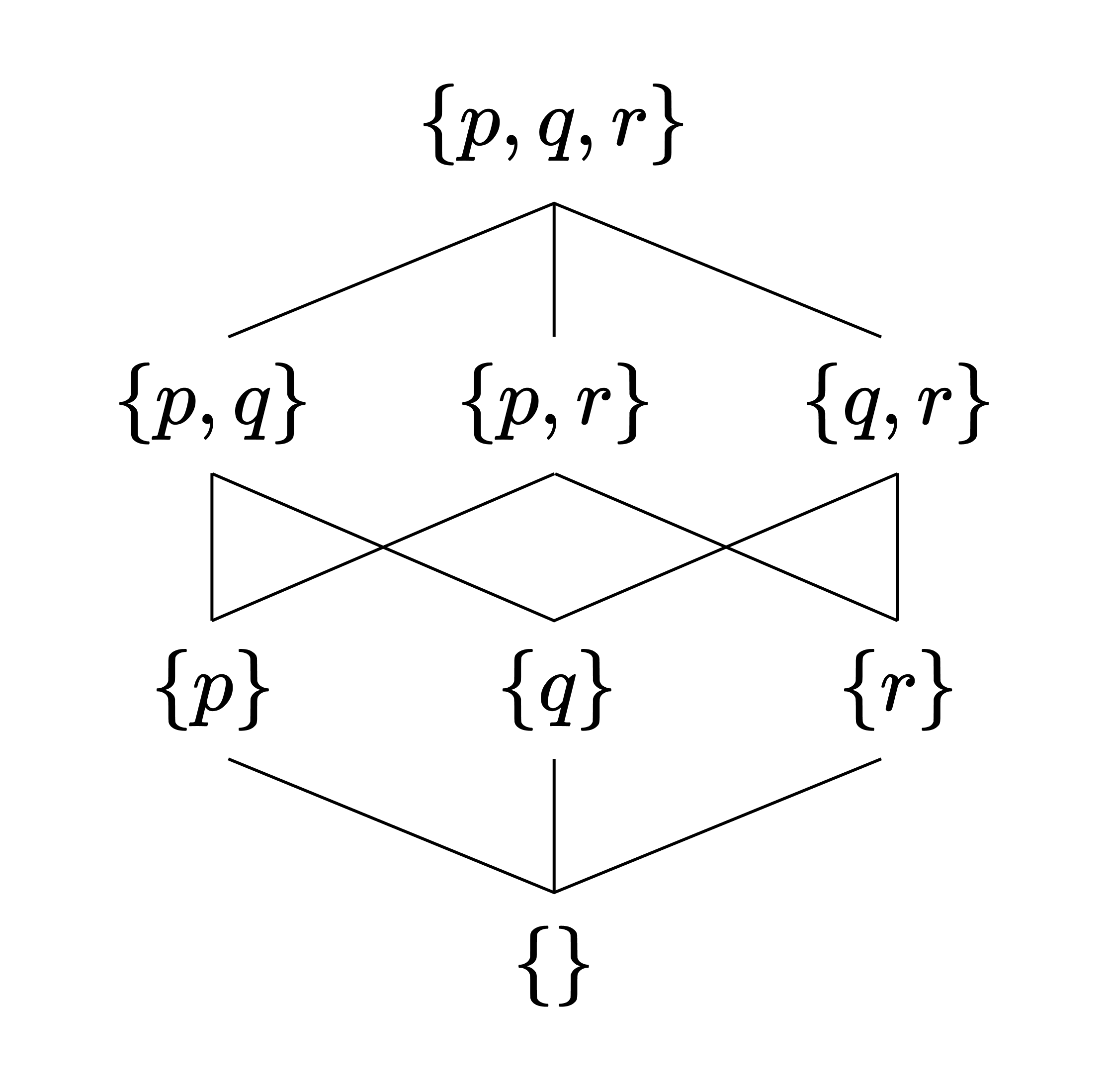

The proof is omitted. Since a Boolean algebraic structure $A$ can be given a partial order $\leq$ in this natural way, we can draw the Hasse diagram of $A$ according to $\leq$. For instance, consider the Boolean algebraic structure formed by $\mathcal{P}(X)$ for $X = \lbrace p, q, r\rbrace $ seen earlier.

\[a \leq b \iff a = a \land b \iff a = a \cap b \iff a \subseteq b\]So in this case, the Hasse diagram of the Boolean algebraic structure is the same as the inclusion diagram of sets.

Boolean Rings

Boolean algebraic structures require two operations and the corresponding identity elements for each operation, which makes their definition similar to that of rings. This is not mere coincidence.

Definition. A ring $R$ is a Boolean ring if for any $x \in R$, we have $x^2 = x$.

Boolean algebraic structures and Boolean rings are in one-to-one correspondence. That is, the following holds:

Theorem. If $(R, 0, 1, +, \cdot)$ is a Boolean ring, then $(R, 0, 1, \lor, \cdot, (\cdot)^{-1})$ is a Boolean algebraic structure, where $\lor, \lnot$ are defined as follows:

\[\begin{gather} x \lor y = x + y + xy \\ \lnot x = 1 + x \end{gather}\]Conversely, if $(A, 0, 1, \lor, \land, \lnot)$ is a Boolean algebraic structure, then $(A, 0, 1, +, \land)$ is a Boolean ring, where $+$ is defined as follows:

\[x + y = (x \lor y) \land \lnot (x \land y)\]

The proof is routine and is omitted. (Use the fact that in a boolean ring, $x + x = 0$.)

Ideals

Recall the following definition from algebra:

Definition. For a ring $R$, a non-empty subset $I \subseteq R$ is an ideal if $I$ forms a group under addition and for any $a \in R$ and $x \in I$, we have $ax \in I$. That is, $aI \subseteq I$.

Building on the correspondence between Boolean algebraic structures and Boolean rings, let us define:

Definition. For a Boolean algebraic structure $A$, a non-empty subset $I \subseteq A$ is an ideal if $I$ is closed under $\lor$ and for any $a \in A$ and $x \in I$, we have $a \land x \in I$. That is, $a \land I \subseteq I$.

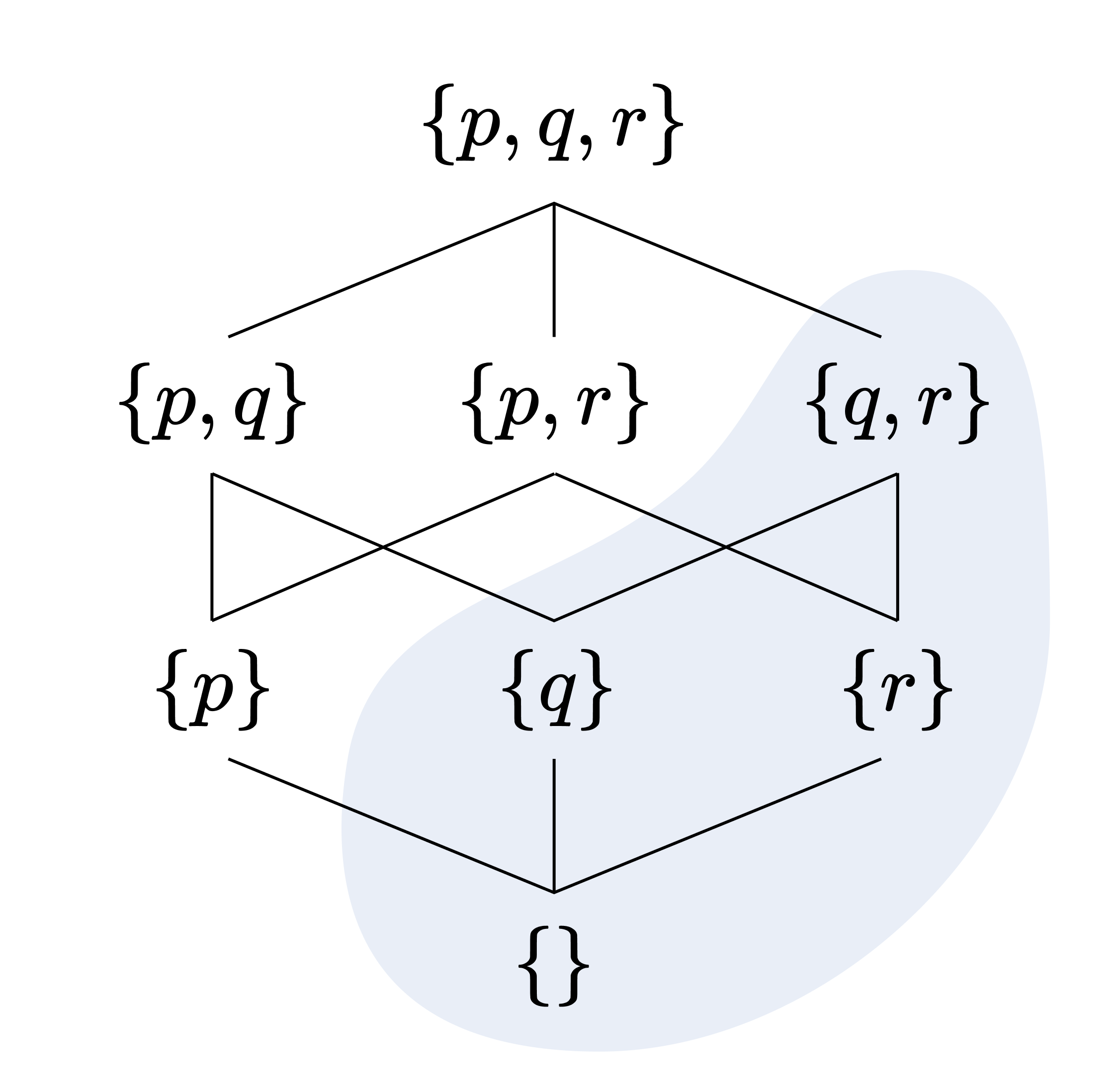

For example, the following shaded region is an ideal of $\mathcal{P}(\lbrace p, q, r\rbrace )$:

When we correspond a Boolean algebraic structure to a Boolean ring, $I$ being an ideal in the former is equivalent to being an ideal in the latter. That is, the following holds:

Theorem. For a Boolean algebraic structure $A$, $I \subseteq A$ is a (Boolean) ideal if and only if $I$ is a (ring) ideal in the corresponding Boolean ring $A$.

We can also define prime ideals and maximal ideals in Boolean algebraic structures.

Definition. Let $I$ be an ideal of the Boolean algebraic structure $A$. $I$ is a prime ideal if for any $a, b \in A$, if $a \land b \in I$, then $a \in I$ or $b \in I$. $I$ is a maximal ideal if whenever $J$ is an ideal that strictly contains $I$, we have $J = A$.

These concepts also correspond exactly to prime ideals and maximal ideals of Boolean rings. Verify that the example ideal shown earlier is both a prime ideal and a maximal ideal. As will soon become apparent, this is not a coincidence.

Let us observe several facts. Let $I \subset A$ be an ideal.

-

For any $a \in I$, by the definition of an ideal, it follows that $a \land \lnot a = 0 \in I$. Therefore, ideals of Boolean algebras always contain $0$ as an element.

-

If $1 \in I$, then for any $a \in A$, it follows that $1 \land a = a \in I$. Therefore, the ideal containing $1$ as an element is uniquely the entire structure.

-

If $I$ is a prime ideal, then for any $a \in A$, since $a \land \lnot a = 0 \in I$, we have $a \in I$ or $\lnot a \in I$. That is, prime ideals always contain either any element or its negation.

-

Let $I$ be a maximal ideal. If there exists some $a \in A$ such that $a \not\in I, \lnot a \not\in I$, then $I \cup \lbrace x \land a : x \in A \rbrace$ is an ideal that strictly contains $I$ but is not the entire $A$, so $I$ is not maximal. Therefore, maximal ideals also always contain either any element or its negation.

From the above facts, with a little reasoning, we can deduce the following:

Theorem. Let $A$ be a Boolean algebraic structure and $I$ be an ideal of $A$. The following are equivalent:

- $I$ is a prime ideal.

- $I$ is a maximal ideal.

- For any $x \in A$, either $x \in I$ or $\lnot x \in I$.

Filters

Filters were discussed in a previous post. Let us recall the definition:

Definition. Let $X$ be a set. A collection $\mathcal{F}$ of subsets of $X$ is called a filter on $X$ if it satisfies the following:

- $X \in \mathcal{F}$

- $\varnothing \not\in \mathcal{F}$

- Upward closure: $A \in \mathcal{F}, A \subset B \implies B \in \mathcal{F}$

- Finite intersection closure: $A, B \in \mathcal{F} \implies A \cap B \in \mathcal{F}$

Translating this definition to Boolean algebraic structures gives us:

Definition. For a Boolean algebraic structure $A$, $F \subseteq A$ is a filter if $F$ is closed under $\land$ and for any $a \in A$ and $x \in I$, we have $a \lor x \in I$. That is, $a \lor I \subseteq I$.

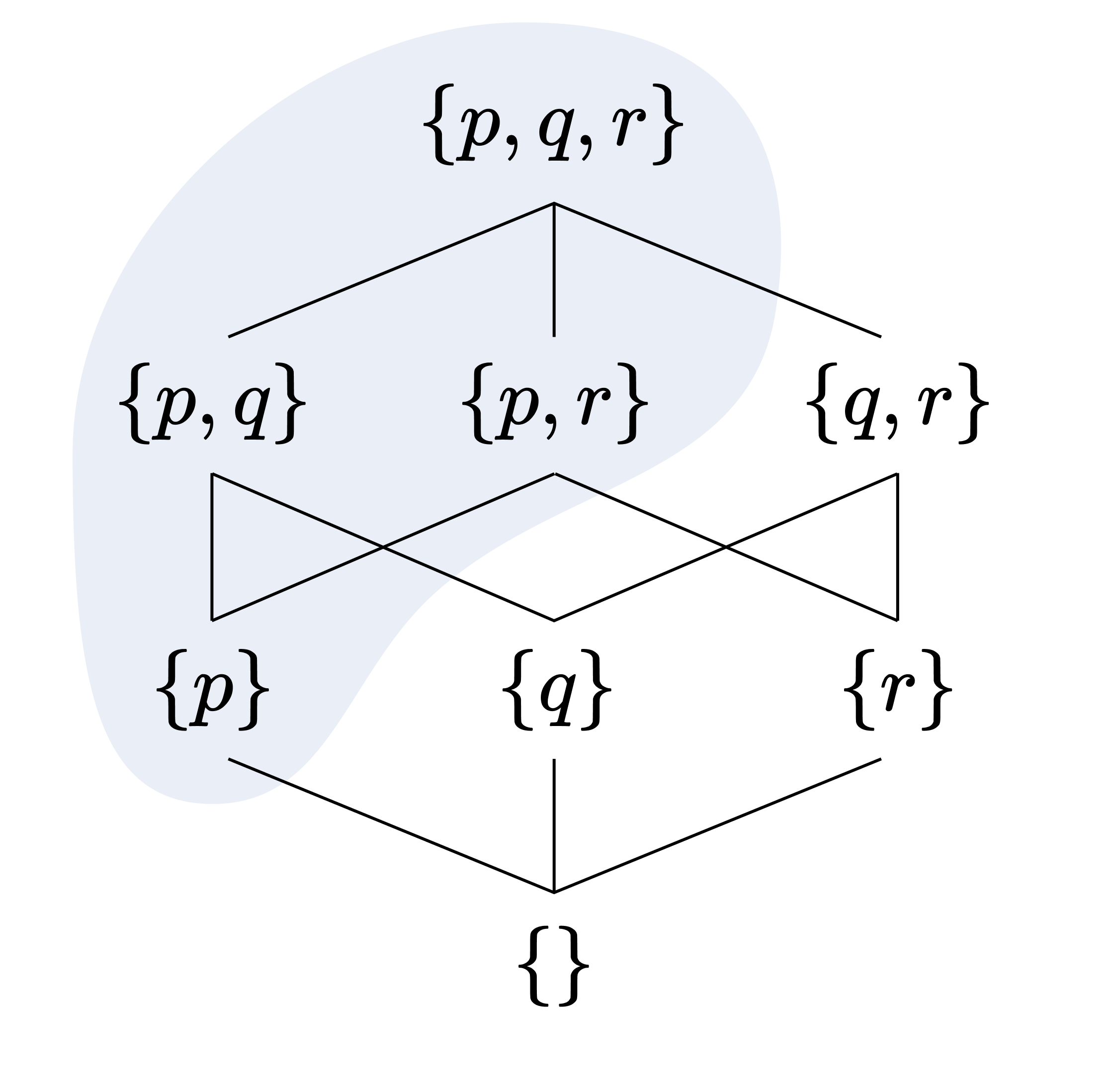

Being closed under $\land$ corresponds to the original “finite intersection closure” condition, and $a \lor I \subseteq I$ corresponds to the original “upward closure” condition. In particular, $a \lor I \subseteq I$ means that if we think of the Boolean algebraic structure as a flow of water flowing in the direction of $\leq$, when ink is dropped at $x \in I$, all regions where the ink spreads are contained in $I$ (compare this with the ink example from the previous post). For example, the following shaded region is a filter of $\mathcal{P}(\lbrace p, q, r\rbrace )$:

Duality Between Ideals and Filters

Comparing the definitions of ideals and filters reveals an interesting fact. If we swap $\land$ and $\lor$ in one definition, we get exactly the other definition. We say that ideals and filters are dual to each other.

Due to this duality, facts proved for one concept naturally hold for the other concept as well. For instance, the following holds:

Theorem. Let $A$ be a Boolean algebraic structure and $F$ be a filter of $A$. The following are equivalent:

- If $x \lor y \in F$, then $x \in F$ or $y \in F$.

- If $G$ is a filter that strictly contains $F$, then $G = A$.

- For any $x \in A$, either $x \in F$ or $\lnot x \in F$.

Here, a filter satisfying the first condition is called a prime filter, one satisfying the second condition is called a maximal filter. Unlike the case of ideals, filters satisfying the third condition also have a name: ultrafilters (see also the previous post).

Booleanisation of Boolean Algebraic Structures Using Ultrafilters

General Boolean algebraic structures, unlike the Boolean algebra familiar to us, do not have each element dichotomised into true or false. $p$ is at the same or closer “distance” from $1$ (true) compared to $p \land q$, but it is neither $0$ nor $1$ in itself.

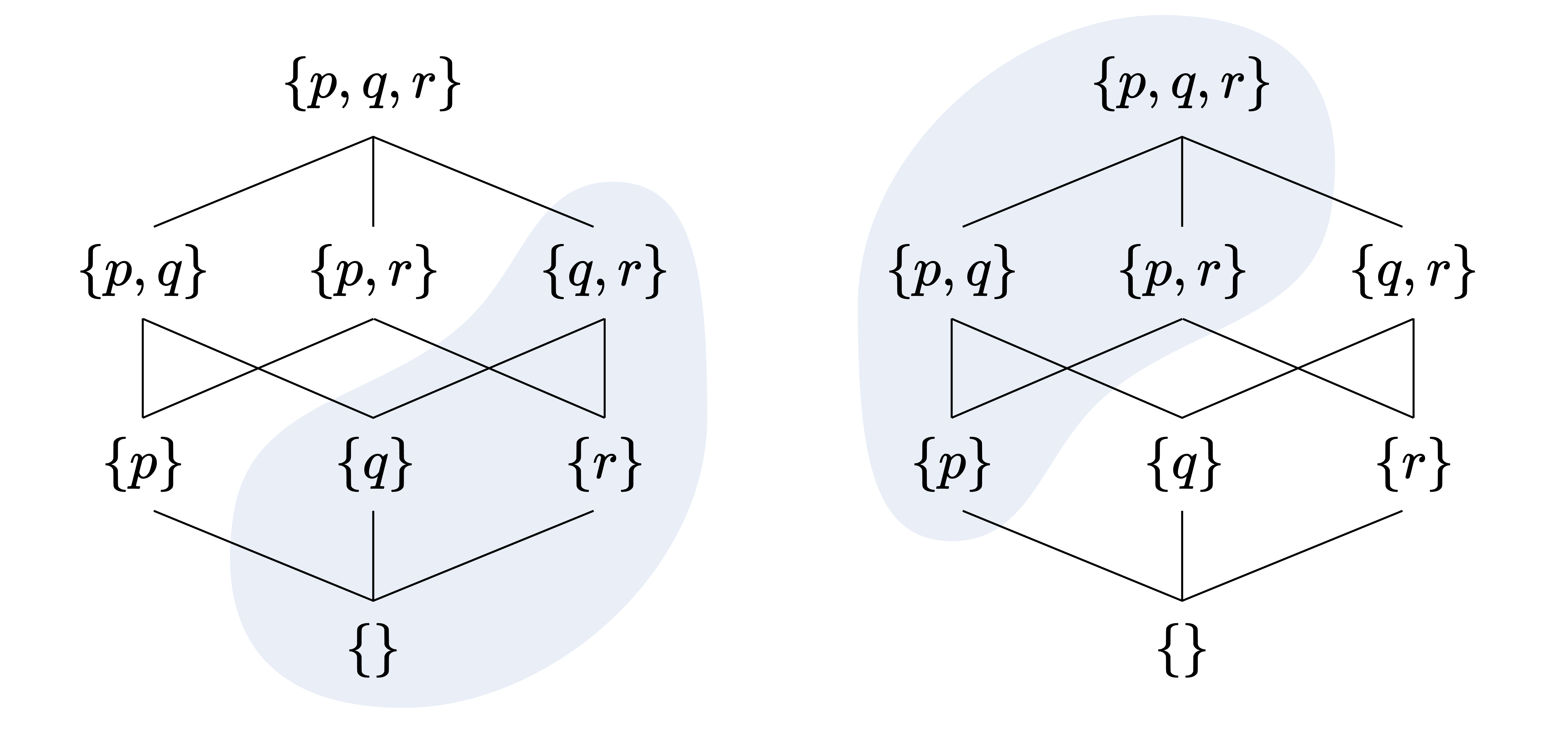

However, when an ultrafilter or prime ideal of a Boolean algebraic structure $A$ is given, we can dichotomise the elements of $A$ into “true” or “false” based on whether they belong to that filter (ideal). Consider again the ideal example (left) and filter example (right) seen earlier. The left is a prime ideal, and the right is an ultrafilter.

Note that they are exactly complements of each other. Generally, the following holds:

Theorem. For a subset $I$ of a Boolean algebraic structure $A$, $I$ is a prime (maximal) ideal if and only if $A \setminus I$ is an ultra-(prime, maximal) filter.

Building on this, let us map elements of $A$ that belong to the prime ideal $I$ to $0$, and those that do not belong to $1$. Or to put in other words, let us map elements of $A$ that belong to the ultrafilter $F$ to $1$, and those that do not belong to $0$. Using the example just given:

| Element | Value |

|---|---|

| $\lbrace \rbrace $ | $0$ |

| $\lbrace p\rbrace $ | $1$ |

| $\lbrace q\rbrace $ | $0$ |

| $\lbrace r\rbrace $ | $0$ |

| $\lbrace p, q\rbrace $ | $1$ |

| $\lbrace p, r\rbrace $ | $1$ |

| $\lbrace q, r\rbrace $ | $0$ |

| $\lbrace p, q, r\rbrace $ | $1$ |

The result is a model of propositional logic. In particular, setting $P = \lbrace p \rbrace , Q = \lbrace q \rbrace , R = \lbrace r \rbrace $ and rewriting the table according to the correspondence $\cup \leftrightarrow \lor, \cap \leftrightarrow \land$ gives:

| Element | Value |

|---|---|

| $\varnothing$ | $0$ |

| $P$ | $1$ |

| $Q$ | $0$ |

| $R$ | $0$ |

| $P \lor Q$ | $1$ |

| $P \lor R$ | $1$ |

| $Q \lor R$ | $0$ |

| $P \lor Q \lor R$ | $1$ |

This is a model of propositional logic where $P$ is true and $Q, R$ are false. In this way, generally when a Boolean algebraic structure is given a prime ideal or ultrafilter, we can construct a logical model based on that information. This is a stepping stone towards the Stone representation theorem.