Homomorphisms, Embeddings, and Elementary Embeddings

01 May 2025This post was originally written in Korean, and has been machine translated into English. It may contain minor errors or unnatural expressions. Proofreading will be done in the near future.

For convenience, this article takes the approach of reducing function expressions $f(a) = c$ to binary predicates $F(a, c)$, rather than treating predicates and functions as separate objects.

Definition. Let $\mathfrak{A}, \mathfrak{B}$ be structures of language $\mathcal{L}$. A mapping $f: \mathfrak{A} \to \mathfrak{B}$ satisfying the following is called a homomorphism. For any relation $R$ in $\mathcal{L}$ and arbitrary $a_1, \dots, a_n \in \mathfrak{A}$,

\[R^\mathfrak{A}(a_1, \dots, a_n) \implies R^\mathfrak{B}(f(a_1), \dots, f(a_n))\]Additionally, when a homomorphism $f$ is injective and satisfies the following, we call $f$ an embedding.

\[R^\mathfrak{A}(a_1, \dots, a_n) \iff R^\mathfrak{B}(f(a_1), \dots, f(a_n))\]

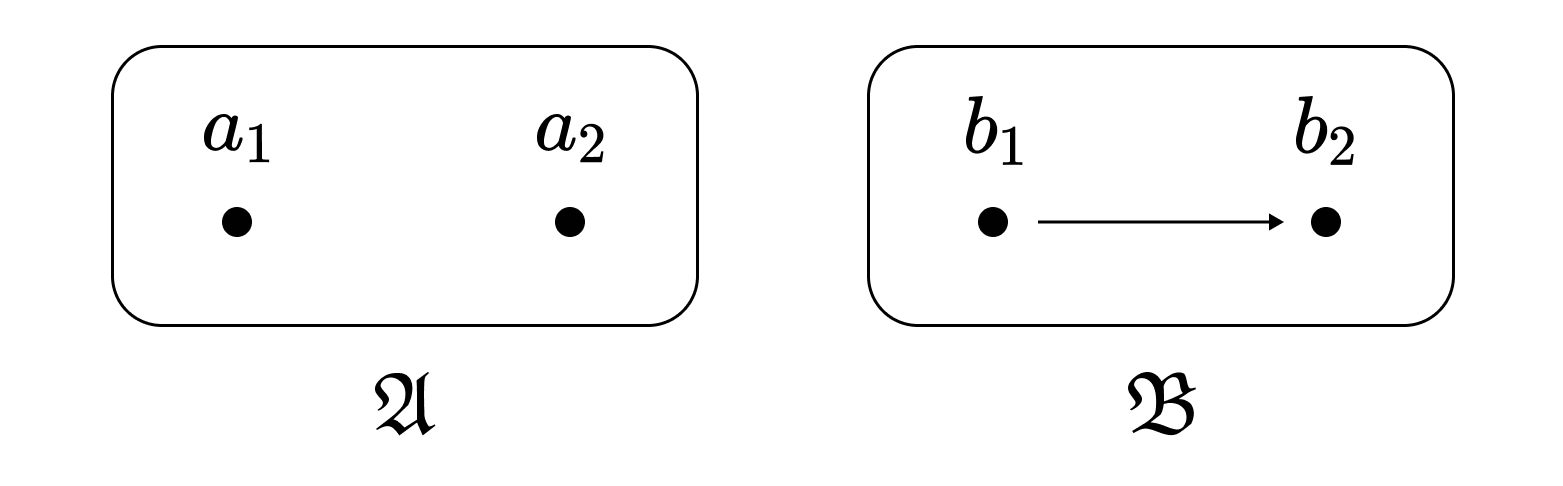

An injective homomorphism is not necessarily an embedding. For example, consider the following two structures of language $\mathcal{L}$ with one binary relation $<$. Objects satisfying $<$ are indicated by arrows. That is, $b_1 <^\mathfrak{B} b_2$.

Since no elements in $\mathfrak{A}$ satisfy $<^\mathfrak{A}$, the mapping $f: a_1 \mapsto b_1, a_2 \mapsto b_2$ is trivially a homomorphism and is injective. However, $f$ is not an embedding. If $f$ were an embedding, then from $b_1 <^\mathfrak{B} b_2$ it would follow that $a_1 <^\mathfrak{A} a_2$. That is, an embedding must preserve not only the elements of $\mathfrak{A}$ but also the relationships between elements in $\mathfrak{B}$. In this respect, embeddings are similar to full functors in category theory.

Definition. Let $\mathfrak{A}$ be a structure of language $\mathcal{L}$. Define $\mathcal{L}_\mathfrak{A}$ as the language obtained by adding to $\mathcal{L}$ as many constants as the size of the domain of $\mathfrak{A}$.

For example with Peano arithmetic, when $\mathcal{L} = (0, S, +)$ and $\mathfrak{A}$ is the standard model of arithmetic, then $\mathcal{L}_\mathfrak{A} = (0, 1, 2, 3, \dots, S, +)$.

Definition. Let $\Delta_\mathfrak{A}^+$ denote the set of all $\mathcal{L}_\mathfrak{A}$-atomic propositions satisfied by $\mathfrak{A}$. That is,

\[\Delta_\mathfrak{A}^+ = \{ R(c_1, \dots, c_n) \mid R, c_i \in \mathcal{L}_\mathfrak{A}, \; \mathfrak{A} \vDash R^{\mathfrak{A}}(c_1^\mathfrak{A}, \dots, c_n^\mathfrak{A}) \}\]Additionally, let $\Delta_\mathfrak{A}$ denote the set obtained by adding to $\Delta_\mathfrak{A}^+$ the negations of all $\mathcal{L}$-atomic propositions not satisfied by $\mathfrak{A}$. That is,

\[\Delta_\mathfrak{A} = \Delta_\mathfrak{A}^+ \cup \{ \lnot R(c_1, \dots, c_n) \mid R, c_i \in \mathcal{L}_\mathfrak{A}, \; \mathfrak{A} \not\vDash R^{\mathfrak{A}}(c_1^\mathfrak{A}, \dots, c_n^\mathfrak{A}) \}\]

The notation $\Delta$ is related to the arithmetic hierarchy.

Since $\Delta_\mathfrak{A}$ is obtained by adding the negations of atomic propositions missing from $\Delta_\mathfrak{A}^+$, the two sets contain essentially the same information. Nevertheless, we define the two sets separately because of the following theorem.

Theorem. Let $\mathfrak{A}, \mathfrak{B}$ be $\mathcal{L}$-structures.

- There exists an injective homomorphism $f: \mathfrak{A} \to \mathfrak{B}$ if and only if $\mathfrak{B}$ is an $\mathcal{L}\mathfrak{A}$-model of $\Delta\mathfrak{A}^+$.

- There exists an embedding $f: \mathfrak{A} \to \mathfrak{B}$ if and only if $\mathfrak{B}$ is an $\mathcal{L}\mathfrak{A}$-model of $\Delta\mathfrak{A}$.

That is, when $\mathfrak{B}$ satisfies $\Delta_\mathfrak{A}^+$, there is a possibility that $\mathfrak{B}$ satisfies atomic propositions ‘excessively’, preventing $\mathfrak{A}$ from being embedded into $\mathfrak{B}$. However, when $\mathfrak{B}$ satisfies $\Delta_\mathfrak{A}$, there are constraints on which atomic propositions $\mathfrak{B}$ can satisfy, thus guaranteeing the possibility of embedding.

In a previous article, we introduced the concept of elementary submodel. From this, we can define the following concept.

Definition. When $f: \mathfrak{A} \to \mathfrak{B}$ is an embedding and $f[\mathfrak{A}]$ is an elementary submodel of $\mathfrak{B}$, we call $f$ an elementary embedding.

The set of sentences related to elementary embeddings is as follows.

Definition. Let $E(\mathfrak{A})$ denote the set of all $\mathcal{L}_\mathfrak{A}$-propositions satisfied by $\mathfrak{A}$. That is,

\[E(\mathfrak{A}) = \{ \phi : \mathfrak{A} \vDash \phi \}\]

The most distinguishing feature of $E(\mathfrak{A})$ from $\Delta_\mathfrak{A}$ is that it also includes sentences with quantifiers.

Theorem. Let $\mathfrak{A}, \mathfrak{B}$ be $\mathcal{L}$-structures. There exists an elementary embedding $f: \mathfrak{A} \to \mathfrak{B}$ if and only if $\mathfrak{B}$ is an $\mathcal{L}_\mathfrak{A}$-model of $E(\mathfrak{A})$.

Finally, the following set of sentences is worth mentioning.

Definition. Let $\mathfrak{A}$ be an $\mathcal{L}$-structure. Let $\mathrm{Th}(\mathfrak{A})$ denote the set of all $\mathcal{L}$-sentences true in $\mathfrak{A}$.

Theorem. Let $\mathfrak{A}, \mathfrak{B}$ be $\mathcal{L}$-structures. $\mathfrak{A}$ and $\mathfrak{B}$ are elementarily equivalent if and only if $\mathrm{Th}(\mathfrak{A}) = \mathrm{Th}(\mathfrak{B})$.

In fact, this is nothing more than the definition of elementary equivalence, so it hardly deserves to be called a theorem, but it has been included here to maintain consistency with the other theorems introduced in this article.

Summarising in a table:

| Definition | Example | Mapping | |

|---|---|---|---|

| $\Delta_\mathfrak{A}^+$ | $\mathcal{L}_\mathfrak{A}$-atomic propositions satisfied by $\mathfrak{A}$ | $0 < 1$ | Surjective homomorphism |

| $\Delta_\mathfrak{A}$ | $\Delta_0$ $\mathcal{L}_\mathfrak{A}$-propositions satisfied by $\mathfrak{A}$ | $\lnot(1 < 0)$ | Embedding (submodel) |

| $\mathrm{Th}(\mathfrak{A})$ | $\mathcal{L}$-propositions satisfied by $\mathfrak{A}$ | $\forall x \exists y (x < y)$ | Elementary equivalence |

| $E(\mathfrak{A})$ | $\mathcal{L}_\mathfrak{A}$-propositions satisfied by $\mathfrak{A}$ | $\not \exists x (x < 0)$ | Elementary embedding (elementary submodel) |

For example, $\mathfrak{A} = (\mathbb{N}, <)$ embeds into $\mathfrak{B} = (\mathbb{Z}, <)$, but does not embed elementarily. This is because $\mathfrak{B}$ does not satisfy the sentence $\not \exists x (x < 0)$ from $E(\mathfrak{A})$.