A Colouring Problem Equivalent to the Continuum Hypothesis

24 Apr 2025This post was originally written in Korean, and has been machine translated into English. It may contain minor errors or unnatural expressions. Proofreading will be done in the near future.

Problem. When the coordinate plane is coloured using countably many colours, does there always exist a right triangle whose three vertices are of the same colour?

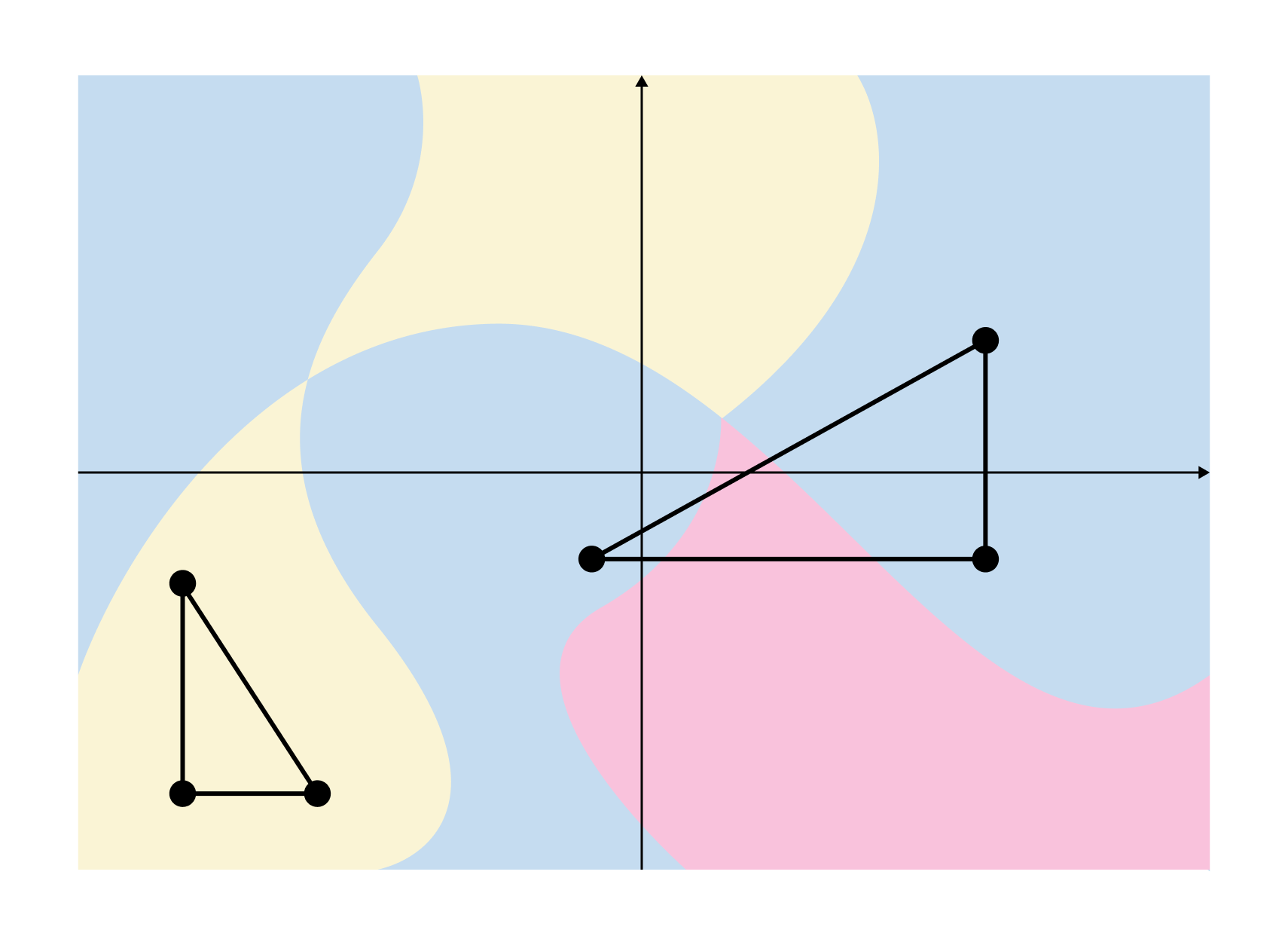

For instance, the following colouring uses 3 colours, and one can easily find a right triangle whose three vertices are all of the same colour.

Of course, the above case is a simple one, and we must consider whether the required right triangle exists even when infinitely many colours are applied in a highly irregular manner, as shown below.

Remarkably, this problem, which appears trivial at first glance, is equivalent to the continuum hypothesis.

Continuum Hypothesis. There exists no infinite set whose cardinality is greater than that of the natural numbers but smaller than that of the real numbers.

We define $\aleph_0$ as the cardinality of the smallest infinite set, namely the natural numbers, and $\aleph_1$ as the cardinality of the smallest infinite set larger than the natural numbers. Meanwhile, the real numbers can easily be shown to have the same cardinality as the power set of the natural numbers, and since the power set of a set $X$ has cardinality $2^{|X|}$, the cardinality of the real numbers is $2^{\aleph_0}$. Therefore, the statement of the continuum hypothesis is equivalent to $\aleph_1 = 2^{\aleph_0}$.

Theorem. A counterexample to the problem exists if and only if $\aleph_1 = 2^{\aleph_0}$.

Note that the following proof is conceived by the author and may contain errors.

Proof. We shall show that if $\aleph_1 = 2^{\aleph_0}$, then a counterexample to the problem exists, and conversely, if a counterexample to the problem exists, then $\aleph_1 = 2^{\aleph_0}$.

If $\aleph_1 = 2^{\aleph_0}$, then a counterexample to the problem exists.

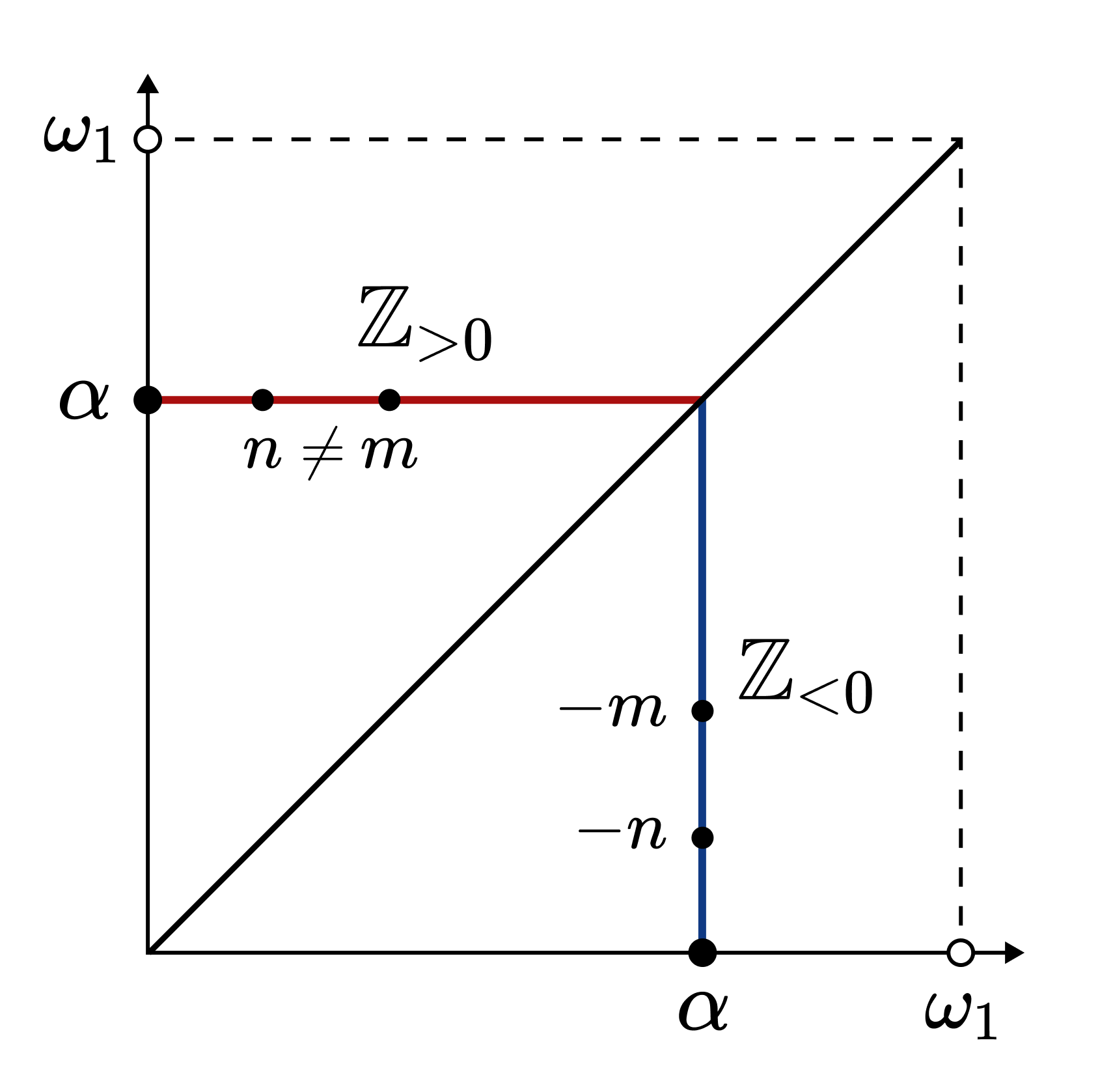

For the smallest uncountable ordinal $\omega_1$, there exists a method of colouring $\omega_1^2$ such that no right triangle with three vertices of the same colour exists. First, we establish a one-to-one correspondence between countably many colours and the integers. Since $\alpha < \omega_1$ is a countable ordinal, we can colour all points of the red segment $\lbrace (\beta, \alpha) : 0 \leq \beta \leq \alpha \rbrace $ with countably many distinct colours. We colour these points with colours corresponding to positive integers. Meanwhile, the points of the blue segment $\lbrace (\alpha, \beta) : 0 \leq \beta < \alpha \rbrace $ are coloured with colours corresponding to negative integers.

It can easily be shown that with this colouring, there exists no right triangle whose three vertices are all of the same colour.

If $\aleph_1 = 2^{\aleph_0}$, then there exists a one-to-one correspondence $f: \mathbb{R} \to \omega_1$. We now define a colouring of the plane as follows. A point $p = (x, y) \in \mathbb{R}^2$ is coloured with the same colour as the point $f(p) = (f(x), f(y)) \in \omega_1^2$. Since $f$ is a one-to-one correspondence, if points $p_1, p_2, p_3$ form the three vertices of a right triangle of the same colour under this colouring, then $f(p_1), f(p_2), f(p_3)$ also form the three vertices of a right triangle of the same colour. However, since we have shown that no such triangle exists in $\omega_1^2$, the plane also lacks the required right triangle under this colouring.

If a counterexample to the problem exists, then $\aleph_1 = 2^{\aleph_0}$.

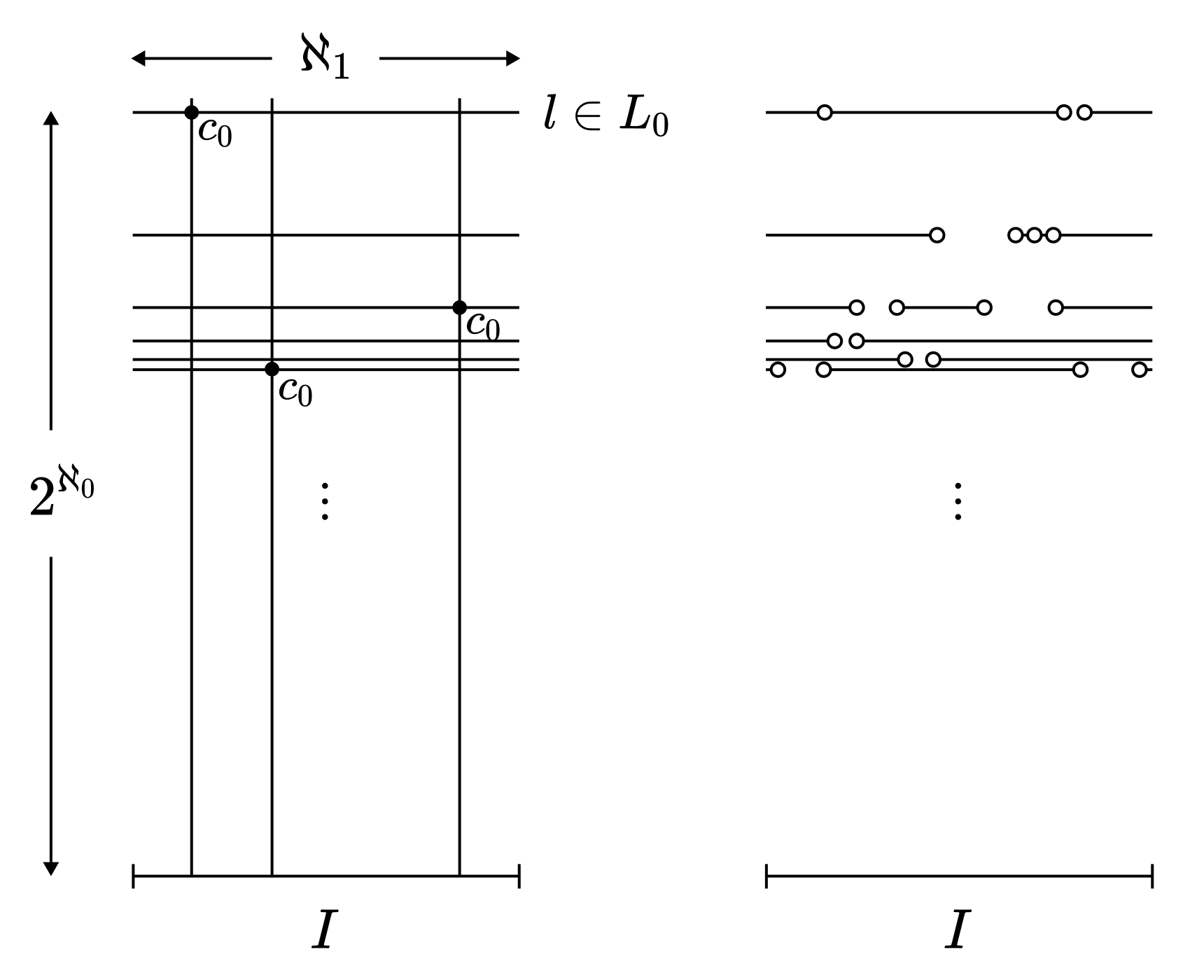

Suppose $2^{\aleph_0} > \aleph_1$ and derive a contradiction. Let $I$ be a subset of the real numbers with cardinality $\aleph_1$. Consider the subset $X = I \times \mathbb{R}$ of the plane.

Let $L_0$ denote the set of lines in $X$ parallel to the $x$-axis. For $l \in L_0$, we write $c \in \aleph_1(l)$ when the number of points in $l$ coloured with colour $c$ is at least $\aleph_1$. For any $l \in L_0$, since $|l| = \aleph_1$, verify that by the pigeonhole principle, there exists at least one colour $c$ such that $c \in \aleph_1(l)$ for each line.

Moreover, since $|L_0| = 2^{\aleph_0}$, by the pigeonhole principle there exists some colour $c_0$ such that the number of lines $l$ satisfying $c_0 \in \aleph_1(l)$ is $2^{\aleph_0}$. Consider the set $L_0’$ of such lines. When vertical lines are drawn through the lines in $L_0’$, if any two intersection points have colour $c_0$, then there exists a right triangle whose three vertices are all of colour $c_0$. Therefore, amongst the intersection points of any vertical line with the lines in $L_0’$, at most one point is coloured $c_0$. Since there are $|I| = \aleph_1$ vertical lines in total, there exist $\aleph_1$ points of colour $c_0$ in $L_0’$.

Removing all these points yields a sparse set of lines. Let this set be $L_1$.

Two cases are possible: a) There are $2^{\aleph_0}$ lines in $L_1$ that contain $\aleph_1$ points. b) There are at most $\aleph_1$ lines in $L_1$ that contain $\aleph_1$ points.

In case a), again by the pigeonhole principle, there exists a colour $c_1$ such that the number of lines $l \in L_1$ satisfying $c_1 \in \aleph_1(l)$ is $2^{\aleph_0}$. Let $L_1’$ denote the set of such lines in $L_1$. By the previous argument, there exist $\aleph_1$ points of colour $c_1$ in $L_1’$. Let $L_2$ denote the set obtained by removing these points. Repeat this process until case b) is reached. (Verify that case b) is eventually reached since there are countably many colours.)

When case b) is reached, $L_n$ contains at most $\aleph_1$ points. However, the number of points removed in the process from $L$ to $L_n$ does not exceed $\aleph_1 \cdot \aleph_0 = \aleph_1$. Meanwhile, since $L$ originally contained $2^{\aleph_0}$ points, this contradicts $\aleph_1 < 2^{\aleph_0}$. ■