Notes on Tensor Products

04 Mar 2025This post was originally written in Korean, and has been machine translated into English. It may contain minor errors or unnatural expressions. Proofreading will be done in the near future.

TL;DR. The tensor product of vector spaces has the following significance:

- A domain for the linearisation of multilinear maps

- A space of multilinear maps

Strictly speaking, 1 corresponds to $U \otimes V$, while 2 corresponds to $U^\ast \otimes V^\ast$. However, these appear to be used interchangeably.

1. Introduction

Definition. Let $U, V, W$ be vector spaces defined over a field $\mathbb{F}$. A map $b: U \times V \to W$ is called a bilinear map if $B$ is linear in each argument. That is, for any $\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{u}_2 \in U, \mathbf{v}_1, \mathbf{v}_2 \in V$ and scalar $\alpha \in \mathbb{F}$, the following hold:

\[b(\alpha \mathbf{u}_1 + \mathbf{u}_2, \mathbf{v}_1) = \alpha b(\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{v}_1) + b(\mathbf{u}_2, \mathbf{v}_1)\] \[b(\mathbf{u}_1, \alpha \mathbf{v}_1 + \mathbf{v}_2) = \alpha b(\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{v}_1) + b(\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{v}_2)\]

For example, the inner product $\cdot : V \times V \to \mathbb{R}$ in real vector spaces is a bilinear map when $\mathbb{R}$ is regarded as a one-dimensional vector space. Similarly, one can define multilinear forms. When $V$ is an $n$-dimensional vector space, $\mathrm{det}: V \times \dots \times V \to \mathbb{R}$ is an $n$-multilinear map.

Let $b: U \times V \to W$ be a bilinear map. Naturally, $b$ is not a linear map. This is because $b$ takes vectors from two different spaces as arguments, rather than vectors from a single space. Even if we consider $b$ as a map from the direct sum $U \oplus V$ to $W$, we have $b(\alpha(u, v)) = b((\alpha u, \alpha v)) = \alpha^2 b(u, v)$, which does not satisfy linearity.

However, using tensor products, we can identify $b$ with a linear map.

2. Definition of Tensor Products

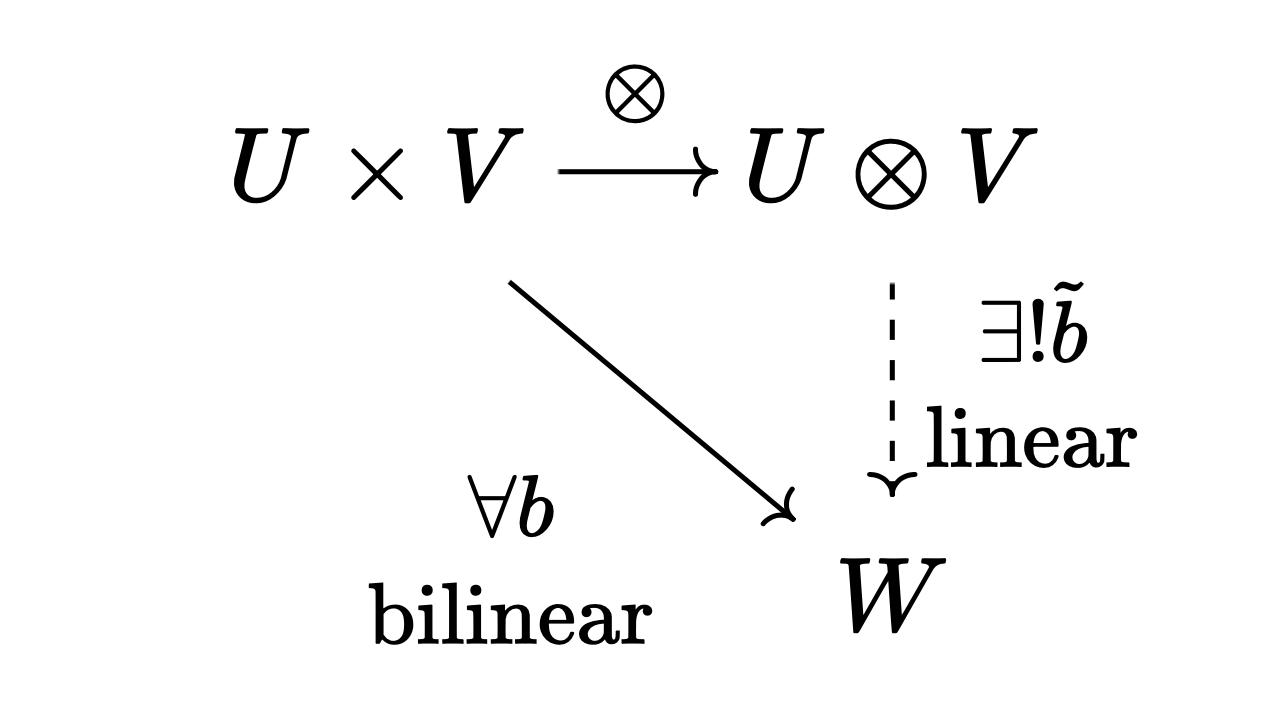

Definition. For vector spaces $U, V$, the tensor product $U \otimes V$ is defined as the vector space satisfying the following universal property:

Elements of $U \otimes V$ are called tensors.

Theorem. The tensor product of any vector spaces always exists and is unique up to isomorphism.

Proof. We prove this only for finite-dimensional vector spaces. Suppose $U$ and $V$ have dimensions $n$ and $m$ respectively, with bases $\lbrace e_1, \dots, e_n\rbrace$ and $\lbrace f_1, \dots, f_m\rbrace$. Let $T$ be a vector space of dimension $nm$. Since vector spaces of the same dimension are isomorphic, such a $T$ is unique up to isomorphism. Let the formal basis of $T$ be:

\[\mathcal{B} = \{ e_1f_1, \dots, e_1f_m, \dots, e_nf_1, \dots, e_nf_m \}\]To show that $T$ is the tensor product of $U$ and $V$, consider an arbitrary bilinear map $b: U \times V \to W$. From $b$, define the following row vector:

\[\tilde {b} = \big[ b(e_1, f_1), \dots, b(e_1, f_m), \dots, b(e_n, f_1), \dots, b(e_n, f_m) \big]_\mathcal{B}\]Also define $\otimes: V \times W \to T$ as follows:

\[\otimes: (u, v) = (u_1e_1 + \dots + u_ne_n, v_1f_1 + \dots + v_mf_m) \mapsto \begin{bmatrix} u_1v_1 \\ \vdots \\ u_1v_m \\ \vdots \\ u_nv_1 \\ \vdots \\ u_nf_m \end{bmatrix}_{\mathcal{B}}\]Then the following holds:

\[\begin{align} \tilde {b}(\otimes(u, v)) &= \sum_i \sum_j (u_i v_j)b(e_i, f_j) \\ &= b\left( \sum_i u_i e_i, \sum_j v_j f_j \right) && (\text{by bilinearity})\\ &= b(u, v) && \blacksquare \end{align}\]3. Identification of Tensors with Multilinear Maps

The discussion thus far can be summarised in one line:

\[\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, W) \cong \mathrm{Hom}(U \otimes V, W)\]Here $\mathrm{Hom}^2$ denotes the space of bilinear maps. In particular, when $W = \mathbb{F}$, by the definition of dual spaces, the following holds:

\[\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F}) \cong \mathrm{Hom}(U \otimes V, \mathbb{F}) \cong (U \otimes V)^*\]Using this relationship, we can view tensor products not merely as domains for the linearisation of bilinear maps, but as spaces of bilinear maps themselves. First, we prove the following lemma.

Lemma. $(U \otimes V)^\ast = U^\ast \otimes V^\ast$

Proof. By the previous relationship and the definition of dual spaces, it suffices to show:

\[\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F}) \cong \mathrm{Hom}(U, \mathbb{F}) \otimes \mathrm{Hom}(V, \mathbb{F})\]That is, we need to show that $\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F})$ satisfies the universal property. This is almost identical to the previous proof, so we omit it. ■

From the lemma, the following holds:

Theorem. $\mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F}) \cong U^\ast \otimes V^\ast$

Proof.

\[\begin{align} U^* \otimes V^* &\cong U^{***} \otimes V^{***} \\ &\cong (U^{**} \otimes V^{**})^* \\ &\cong (U \otimes V)^* \\ &\cong \mathrm{Hom}^2(U \times V, \mathbb{F}) \end{align}\]In going from the second to the third expression, we used the canonical identification $V \cong V^{\ast\ast}$. ■

Therefore, tensors in dual spaces can be canonically identified with bilinear maps.