The Euler-Lagrange Equation and Lagrangian Mechanics

27 Feb 2025This post was originally written in Korean, and has been machine translated into English. It may contain minor errors or unnatural expressions. Proofreading will be done in the near future.

1. Introduction

The trajectory of a particle moving in one dimension can be expressed as $x(t)$. Consider a function $f(x, x’)$ that depends on the particle’s position and velocity. Our objective is to find the path $x(t)$ along which the particle travels from position $x_1$ at time $t_1$ to position $x_2$ at time $t_2$, such that the following quantity is extremised—that is, the path that renders this quantity either maximum or minimum:

\[A[x] = \int^{t_2}_{t_1} f(x, \dot{x}) dt\]The square brackets indicate that the parameter of $A$ is a function rather than a real number. Therefore, intuitively, to find $x(t)$ that minimises $A[x]$, we should establish a differential equation for functions.

\[\frac{dA[x]}{dx(t)} = 0?\]2. The Euler-Lagrange Equation

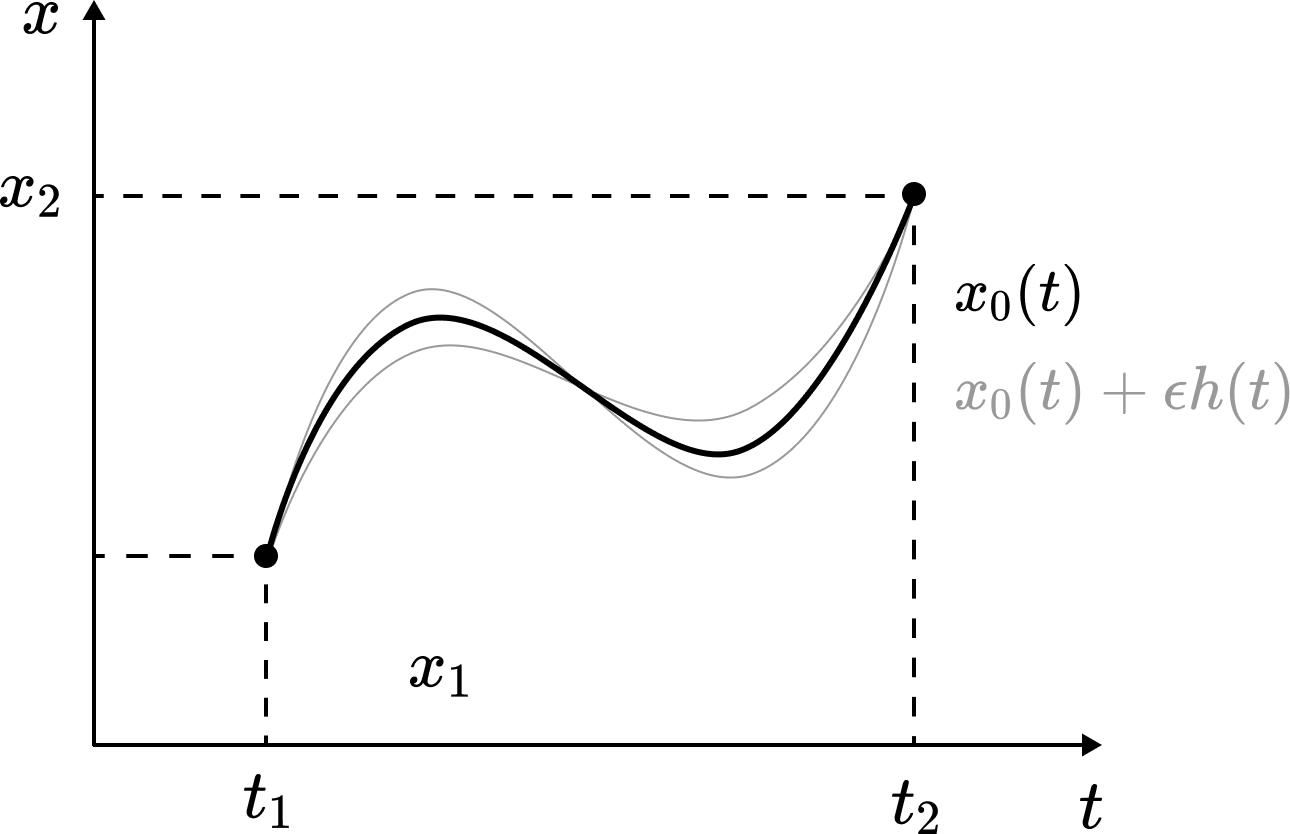

Of course, we have never defined differentiation with respect to functions. However, through a simple trick, we can reduce differentiation with respect to functions to ordinary differentiation. First, let $x_0(t)$ be the path we seek—that is, the path that extremises $A[x]$. A path in the ‘neighbourhood’ of $x_0(t)$ takes the following form:

\[x(\alpha, t) = x_0(t) + \alpha h(t)\]

The boundary conditions are $h(t_1) = h(t_2) = 0$. Since $x_0(t)$ extremises $A[x]$, for sufficiently small $\epsilon$, we have $A[x_0] = A[x(0, t)] \leq A[x(\epsilon, t)]$. Therefore,

\[\left. \frac{dA[x(\alpha, t)]}{d\alpha} \right\vert_{\alpha = 0} = 0\]Expanding the above equation yields:

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{dA}{d\alpha} &= \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{d}{d\alpha} \Big[ f \big( x(\alpha, t), \dot{x}(\alpha, t) \big) \Big] dt \\ &= \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} + \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}}\frac{\partial \dot{x}}{\partial \alpha} \right) dt \\ &= \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} dt + \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \cdot \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} \right) dt \\ &= \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} dt + \left[ \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} \right]^{t_2}_{t_1} - \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \right) \frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} dt \end{aligned}\]Integration by parts is employed in the transition from the third to the fourth equation. Since ${\partial x}/{\partial \alpha} = h(t)$, the second term in the fourth equation vanishes due to the boundary conditions. Therefore,

\[\frac{dA}{d\alpha} = \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} - \frac{d}{dt}\left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \right) \right) \frac{\partial x}{\partial \alpha} dt = 0\]Since the above equation must be satisfied for arbitrary $h \in C^1$, we obtain the following necessary condition for $x(t)$ to extremise $A$:

\[\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = \frac{d}{dt}\left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \right)\]This is the Euler-Lagrange equation. Since extremising the value $A$ is expressed as $\delta A = 0$, the conclusion of the Euler-Lagrange equation can be written as follows:

\[\delta A = 0 \implies \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = \frac{d}{dt}\left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}} \right)\]We have just proved this for functions of one variable, but the same equation holds for functions of multiple variables. That is, let the coordinates representing the motion of some particle(s) be $\lbrace q_i \rbrace _{i \leq n}$. For example, if two particles move in three dimensions, then $n = 6$. The necessary condition for their motion to extremise $\int f(q_1, \dot{q_1}, \dots, q_n, \dot{q_n}) dt$ is that the following holds for each $i$:

\[\frac{\partial f}{\partial q_i} = \frac{d}{dt}\left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{q_i}} \right)\]3. Lagrangian Mechanics

Definition. Let the coordinates representing the motion of the particles in system $S$ be $\lbrace q_i \rbrace _{1 \leq i \leq n}$. The Lagrangian $\mathcal{L}(\lbrace q , \dot{q} \rbrace, t)$ of $S$ is defined as a function such that the equation for the condition that extremises the following quantity becomes identical to the equations of motion of the particles:

\[\mathcal{S} = \int^{t_2}_{t_1} \mathcal{L}(\{ q, \dot{q} \}, t) dt\]$\mathcal{S}$ is called the action.

For example, the Lagrangian of a particle in a one-dimensional potential field $V(x)$ is as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathcal{L}(x, \dot{x}) &= T - V \\ &= \frac{1}{2}m\dot{x}^2 - V(x) \end{aligned}\]Let us verify that the above function is indeed the Lagrangian. Using the Euler-Lagrange equation, the condition for the action corresponding to this Lagrangian to be extremised is as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} \delta \mathcal{S} = 0 &\implies \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial x} = \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{x}} \\ &\iff -\frac{dV}{dx} = \frac{d}{dt}(m\dot{x}) \\ &\iff -\frac{dV}{dx} = m\ddot{x} \end{aligned}\]The final equation is Newton’s equation of motion. Therefore, $\mathcal{L}$ is indeed the Lagrangian of this system. In general, the following holds:

Theorem. The Lagrangian of a classical mechanical system satisfying the following two conditions is given by $\mathcal{L} = T - V$:

- The constraints of the system are holonomic. That is, the constraints depend only on the positions of the particles and not on their velocities.

- The forces $\mathbf{F}_i$ acting on the system have potential functions $U_i(\lbrace q, \dot{q} \rbrace, t)$.

Proof. See the linked SE post.

However, in general, the Lagrangian of a system is not necessarily given by $T - V$. For instance, while the kinetic energy of a relativistic particle is $(\gamma - 1)m_0c^2$, the correct Lagrangian is $-m_0c^2/\gamma$.

Unlike Newtonian mechanics, Lagrangian mechanics has the advantage of permitting very flexible coordinate transformations. This is because, unlike Newtonian mechanics, Lagrangian mechanics possesses general covariance. A detailed explanation of this can be found in the following article.