Ramsey Numbers and the Infinite Ramsey Theorem

20 Feb 2025This post was originally written in Korean, and has been machine translated into English. It may contain minor errors or unnatural expressions. Proofreading will be done in the near future.

Abstract. We examine the definition of Ramsey numbers and the Ramsey theorem that ensures Ramsey numbers are well-defined, extending this to infinite graphs. We also introduce an argument that derives the finite Ramsey theorem from the infinite Ramsey theorem using the compactness theorem.

Introduction

Problem. When the edges of a complete graph with 6 vertices are coloured red or blue, show that there exists a triangle whose three edges are all the same colour.

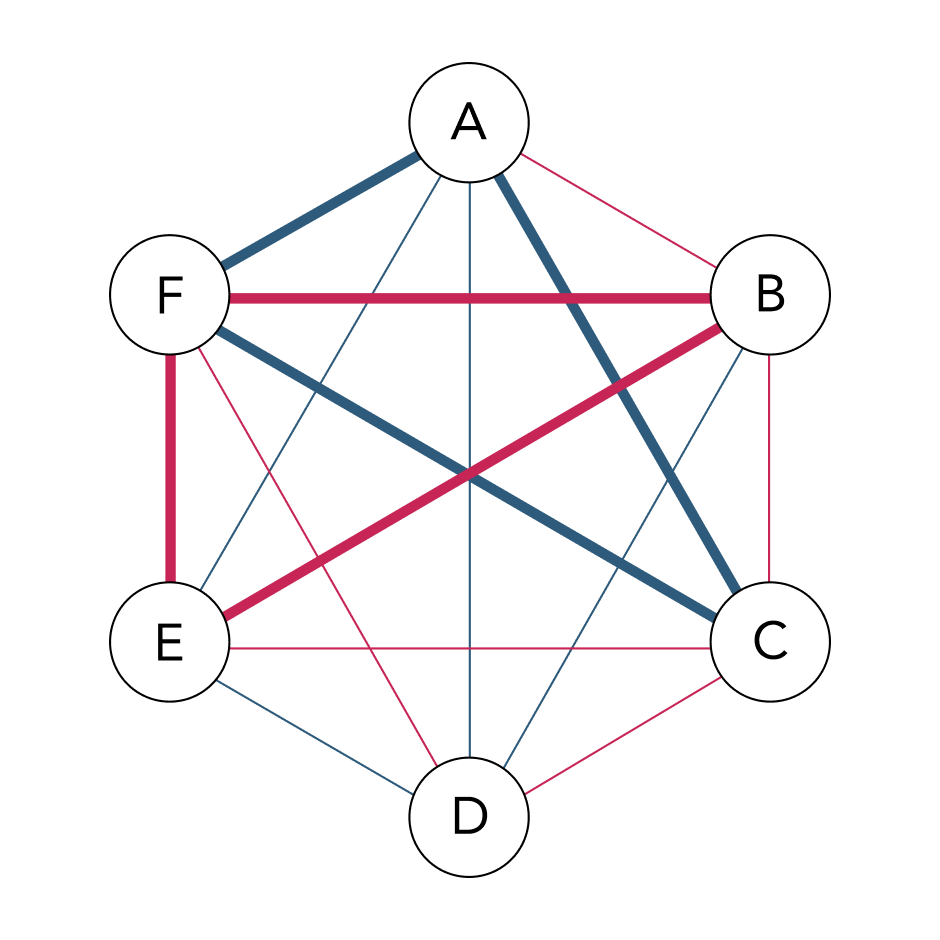

For instance, in the following diagram, triangles ACF and BEF satisfy the problem’s conditions.

Solution. The number of edges emanating from any vertex is 5, so by the pigeonhole principle, at least 3 of them have the same colour. Without loss of generality, suppose edges AB, AC, and AD are all red. If any one of edges BC, CD, or DB is red, then there exists a triangle with all three edges red. For example, if BC is red, then triangle ABC satisfies this condition. On the other hand, if BC, CD, and DB are all blue, then triangle BCD has all three edges blue. Therefore, there exists at least one triangle with all three edges the same colour. ■

Ramsey Theorem

The conclusion of the above problem can be expressed as follows: When $G$ is a complete graph with 6 or more vertices, if the edges of $G$ are coloured red or blue, then either there exists a complete subgraph with 3 or more vertices whose edges are all red, or there exists a complete subgraph with 3 or more vertices whose edges are all blue.

Generalising this conclusion, we can pose the following question: Let $r$ and $b$ be arbitrary natural numbers. Does there exist a natural number $j$ such that when $G$ is a complete graph with $j$ or more vertices and the edges of $G$ are coloured red or blue, it is guaranteed that either there exists a complete subgraph with $r$ or more vertices whose edges are all red, or there exists a complete subgraph with $b$ or more vertices whose edges are all blue?

According to the Ramsey theorem, the answer is yes. Specifically, when the smallest such $j$ is defined as $R(r, b)$, the following holds:

Ramsey Theorem. For any natural numbers $r$ and $b$, $R(r, b)$ exists.

Proof. We prove by induction on $r + b$. It suffices to show that the following holds:

\[R(r, b) \leq R(r-1, b) + R(r, b-1)\]Let $R(r-1, b) = i$ and $R(r, b-1) = j$. Suppose $G$ is a complete graph with $i + j$ vertices, and the edges of $G$ are coloured red or blue. For any vertex $v \in G$, let $R$ be the complete subgraph formed by vertices connected to $v$ by red edges, and let $B$ be the complete subgraph formed by vertices connected by blue edges. The following holds:

\[|R| + |B| + 1 = i + j\]Therefore, one of the following must hold:

-

$ R \geq i$ -

$ B \geq j$

In case 1, since $R(r-1, b) = i$, $R$ either has a complete subgraph with $r-1$ vertices whose edges are all red, or has a complete subgraph with $b$ vertices whose edges are all blue. In the latter case, the condition for $R(r, b)$ is satisfied, and in the former case, the graph obtained by adding $v$ to that subgraph satisfies the condition for $R(r, b)$. The same logic applies to case 2. ■

The problem at the beginning suggests that $R(3, 3) \leq 6$. Since it is known that there exist graphs with 5 vertices that do not satisfy the problem’s conditions, we have $R(3, 3) = 6$. The following are also trivial:

- $R(r, b) = R(b, r)$

- $R(r, 2) = r$

However, calculating Ramsey numbers exactly for general values is an extremely difficult problem. This is because the number of cases to be explored increases faster than exponentially with the number of vertices in the graph. The time complexity of the currently known fastest Ramsey number search algorithm is $O(c^{n^2})$. The problem of finding the value of $R(5, 5)$ remains unsolved, though it is known to be between 43 and 48 inclusive. The following anecdote is told regarding this:

Erdős once told this story. Imagine that a much more advanced alien force lands on Earth and says that unless we calculate the value of $R(5, 5)$, they will blow the Earth to pieces. Erdős claimed that in this case, we should gather all our computers and mathematicians to attempt the calculation. However, if they demanded the value of $R(6, 6)$, Erdős said it would be better to devise a plan to defeat the alien force.¹

Ramsey Theorem for Multiple Colours

The Ramsey theorem also holds when more than two colours are used. First, let us define $R(n_1, n_2, \ldots, n_k) = j$ as the smallest $j$ such that when the edges of a complete graph with $j$ vertices are coloured using $k$ colours, at least one of the following always exists:

- A complete subgraph with $n_1$ vertices whose edges are all the 1st colour

- A complete subgraph with $n_2$ vertices whose edges are all the 2nd colour

- …

- A complete subgraph with $n_k$ vertices whose edges are all the $k$th colour

For example, it is known that $R(3, 3, 3) = 17$. This means that when the edges of a complete graph with 17 or more vertices are coloured red, blue, or yellow, there always exists a triangle whose three edges are all red, all blue, or all yellow.

Ramsey Theorem for Multiple Colours. For any natural numbers $n_1, \ldots, n_k$, $R(n_1, \ldots, n_k)$ exists.

Proof. We prove by induction on $k$. It suffices to show that the following holds:

\[R(n_1, \ldots, n_k) \leq R(n_1, \ldots, n_{k-2}, R(n_{k-1}, n_k))\]Let $j$ be the right-hand side of the inequality. Suppose $G$ is a complete graph with $j$ vertices, and colour the edges of $G$ using $k$ colours. Temporarily identify the $(k-1)$th colour with the $k$th colour. Then, by the definition of $j$, at least one of the following exists in $G$:

- A complete subgraph with $n_1$ vertices whose edges are all the 1st colour

- A complete subgraph with $n_2$ vertices whose edges are all the 2nd colour

- …

- A complete subgraph with $n_{k-2}$ vertices whose edges are all the $(k-2)$th colour

- A complete subgraph with $R(n_{k-1}, n_k)$ vertices whose edges are all the $(k-1)$th colour = $k$th colour

Except for the last case, the condition for $R(n_1, \ldots, n_k)$ is satisfied, so we need only consider the last case. Let $H$ be the complete subgraph guaranteed by the last case. By the definition of $R(n_{k-1}, n_k)$, $H$ has at least one of the following:

- A complete subgraph with $n_{k-1}$ vertices whose edges are all the $(k-1)$th colour

- A complete subgraph with $n_k$ vertices whose edges are all the $k$th colour

Since each case satisfies the condition for $R(n_1, \ldots, n_k)$, in all cases $G$ satisfies $R(n_1, \ldots, n_k)$. ■

Erdős-Rado Arrow

So far, we have examined the colouring of edges. Edges are relationships between two vertices. Going further, we can consider situations where relationships among $n$ vertices are coloured.

For convenience of discussion, let us introduce several definitions. First, we adopt the set-theoretic definition of natural numbers, defining $n = {0, 1, \ldots, n-1}$. We also introduce the following notation:

Definition. When $A$ is a set, we define:

\[A^{(n)} = \{ S: S \subset A, |S| = n \}\]

That is, for a natural number $j$, $j^{(n)}$ is a set whose elements are each case of $_jC_n$. For example,

\[4^{(2)} = \left\{ \{ 0, 1\}, \{0, 2 \}, \{0, 3\}, \{1, 2 \}, \{1, 3\}, \{2, 3\} \right\}\]To partition a given set into $m$ parts means to classify each element of the set into one of $m$ categories. For example, one result of partitioning $4^{(2)}$ into 3 parts is:

\[\left\{ \left\{ \{0, 1\}, \{ 0, 2 \}, \{1, 2\} \right\}, \left\{ \{0, 3\}, \{2, 3 \} \right\}, \left\{ \{1, 3 \} \right\} \right\}\]In the above partition, the sets formed by 0, 1, and 2 all belong to the same category. We say that 0, 1, and 2 are homogeneous with respect to this partition.

We define the following notation, called the Erdős-Rado arrow:

Definition. If there always exist $k$ homogeneous elements when $j^{(n)}$ is partitioned into $m$ parts, we write:

\[j \rightarrow (k)^n_m\]

The problem at the beginning suggests that $6 \rightarrow (3)^2_2$. The reason $n = 2$ is that edges are relationships between two vertices, and $m = 2$ because there are two colours.

By the Ramsey theorem we saw earlier, the following holds:

\[\forall k\; \exists j: j \to (k)^2_2\]Meanwhile, the Ramsey theorem for multiple colours suggests:

\[\forall k, m \; \exists j : j \to (k)^2_m\]In general, the following is known:

Finite Erdős-Rado Theorem. For any natural numbers $n$, $m$, and $k$, there exists a natural number $j$ such that:

\[j \rightarrow (k)^n_m\]

Infinite Ramsey Theorem

Interestingly, the Ramsey theorem also holds when $k$ is an infinite cardinal. The following is known:

Erdős-Rado Theorem. For any cardinal $\lambda$ and natural numbers $n$ and $m$, there exists a cardinal $\kappa$ such that:

\[\kappa \rightarrow (\lambda)^n_m\]

In particular, the following holds:

Infinite Ramsey Theorem. \(\aleph_0 \rightarrow (\aleph_0)^n_m\)

That is, when guests at Hilbert’s hotel arbitrarily shake hands, either there are infinitely many people who all shake hands with each other, or there are infinitely many people who never shake hands with each other.

The proof of the above theorem is the author’s own conjecture, so please let me know if there are any errors.

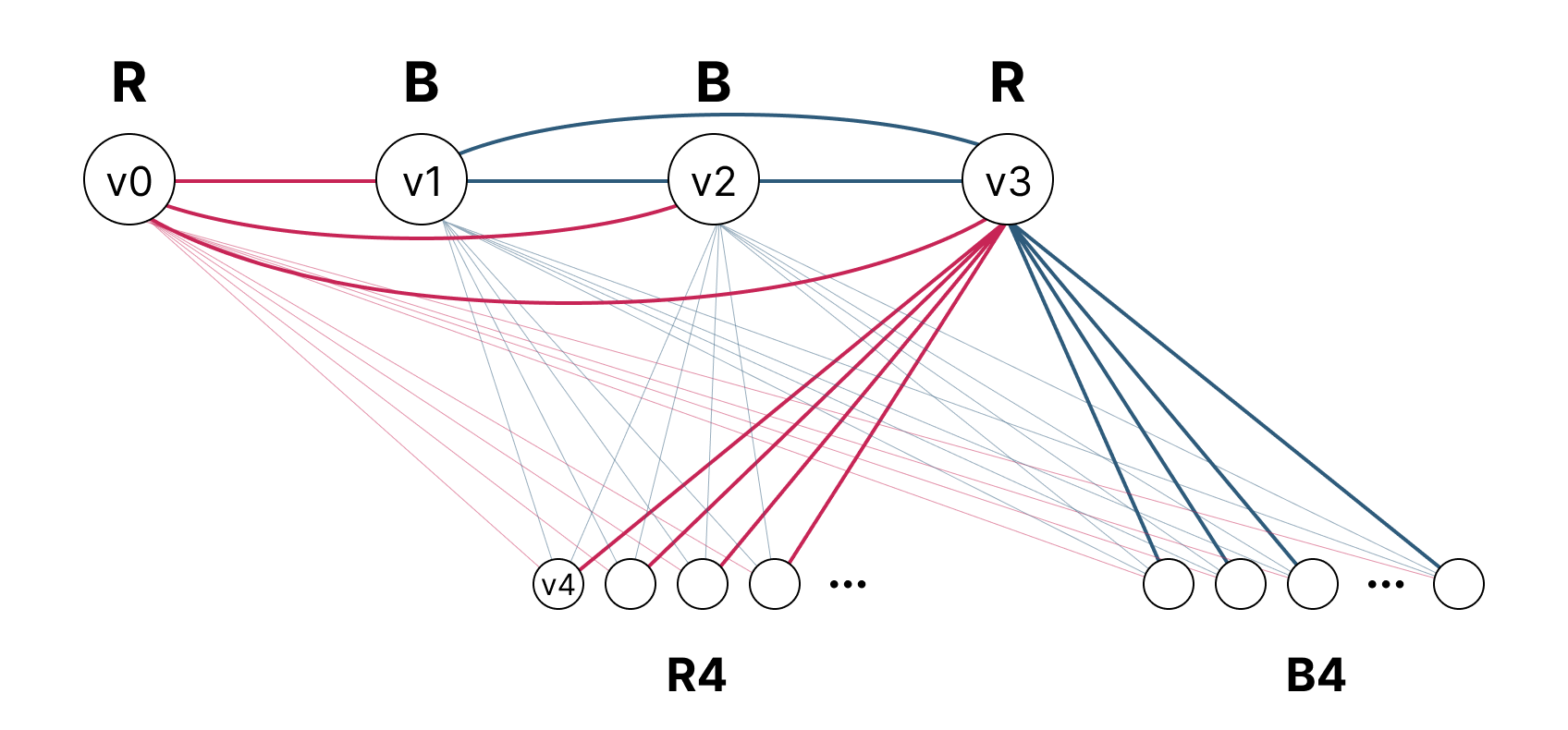

Proof. We prove for the case $n = m = 2$. Suppose $G$ is a complete graph of size $\aleph_0$. Colour the edges of $G$ red or blue. For vertices $v$ and $w$ of $G$, if $\overline{vw}$ is red, we write $\overline{vw} \in R$; if blue, we write $\overline{vw} \in B$.

For any vertex $v_0$ of $G$, define:

\[\begin{aligned} R_1 = \{ w \in G : \overline{v_0w} \in R \}\\ B_1 = \{ w \in G : \overline{v_0w} \in B \} \end{aligned}\]Since $R_1 \cup B_1 \cup {v_0} = G$, at least one of $R_1$ and $B_1$ is an infinite set. If $R_1$ is infinite, we write $v_0 \in R$; if $B_1$ is infinite, we write $v_0 \in B$.

Suppose $R_1$ is infinite. By the axiom of choice, we can select an element $v_1$ of $R_1$. Now define:

\[\begin{aligned} R_2 = \{ w \in R_1 : \overline{v_1w} \in R \}\\ B_2 = \{ w \in R_1 : \overline{v_1w} \in B \} \end{aligned}\]Since $R_2 \cup B_2 \cup {v_1} = R_1$, at least one of $R_2$ and $B_2$ is infinite. Similarly, if $R_2$ is infinite, we write $v_1 \in R$; if $B_2$ is infinite, we write $v_1 \in B$.

Suppose $B_2$ is infinite. Select an element $v_2$ of $B_2$ and define:

\[\begin{aligned} R_3 = \{ w \in B_2 : \overline{v_2w} \in R \}\\ B_3 = \{ w \in B_2 : \overline{v_2w} \in B \} \end{aligned}\]By repeating in this manner, we obtain the following sequence of vertices:

\[V = \{ v_0, v_1, v_2, v_3, \ldots \}\]

For each $v \in V$, either $v \in R$ or $v \in B$. Since $V$ is infinite, one of the following is infinite:

\[\begin{aligned} H = \{ v \in V : v \in R \} \\ K = \{ v \in V : v \in B \} \end{aligned}\]If $H$ is infinite, then the complete graph formed by the vertices of $H$ has all edges red. On the other hand, if $K$ is infinite, then the complete graph formed by the vertices of $K$ has all edges blue. Therefore, $\aleph_0 \rightarrow (\aleph_0)^2_2$. ■

Corollary. When $A$ is an infinite subset of $\mathbb{N}$, there exists an infinite subset $B$ of $A$ such that one of the following holds:

- For any $b \in B$, if $c$ is an element of $B$ greater than $b$, then $b \mid c$.

- For any $b, c \in B$, $b \nmid c$ and $c \nmid b$.

Proof. Take $k = A$, and consider a partition where for $x < y$, if $x \mid y$, then ${x, y}$ is classified into category 1; otherwise, into category 2. Then use the fact that $\aleph_0 \rightarrow (\aleph_0)^2_2$. ■

From Infinite to Finite

Interestingly, using the compactness theorem, one can prove the finite Ramsey theorem from the infinite Ramsey theorem. That is, the following holds:

Lemma. If $\aleph_0 \rightarrow (\aleph_0)^n_m$, then for any natural number $k$, there exists a natural number $j$ such that $j \to (k)^n_m$.

Proof. We prove for the case $n = 2$. A graph whose edges are coloured with $m$ colours can be formalised as follows. First, define the signature of language $\mathcal{L} = (V, f, 1, 2, \ldots, m)$ as:

- $V$ is a unary relation.

- $f$ is a binary function.

- $1, 2, \ldots, m$ are constants.

Let $T$ be an $\mathcal{L}$-theory consisting of:

- $\psi : \lnot V(1) \land \lnot V(2) \land \lnot V(m)$

- $\theta : \forall x, y \; (V(x) \land V(y) \land x \neq y) \rightarrow ( f(x, y) = 1 \lor f(x, y) = 2 \lor \cdots \lor f(x, y) = m )$

- $\phi_1 : \exists x_1, x_2 \; V(x_1) \land V(x_2) \land x_1 \neq x_2$

- $\phi_2 : \exists x_1, x_2, x_3 \; V(x_1) \land V(x_2) \land V(x_3) \land x_1 \neq x_2 \land x_2 \neq x_3 \land x_1 \neq x_3$

- For each $n \in \mathbb{N}$, $\phi_n$

$\psi$ means that $1, 2, \ldots, m$ represent colours, not vertices. $\theta$ means that any edge between two vertices has one of the colours from $1$ to $m$. And $\phi_n$ means that at least $n$ vertices exist. Since $\phi_n \in T$ for any $n$, models of $T$ are infinite complete graphs.

Let the following sentence be $\chi$:

\[\exists x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_k : f(x_1, x_2) = f(x_1, x_3) = \ldots = f(x_{k-1}, x_k)\]That is, $\chi$ means that there exists a monochromatic complete subgraph with $k$ vertices. Therefore, according to the infinite Ramsey theorem, the following holds:

\[T \vDash \chi\]And by the compactness theorem, there exists some finite sub-theory $T’ = {\psi, \theta, \phi_1, \ldots, \phi_j}$ such that:

\[T' \vDash \chi\]That is, every complete graph with $j$ or more vertices satisfies $\chi$. In other words, $j \to (k)^2_m$. To prove for arbitrary $n$, one can take $R$ as an $n$-ary relation. ■

¹ Joel H. Spencer (1994), Ten Lectures on the Probabilistic Method