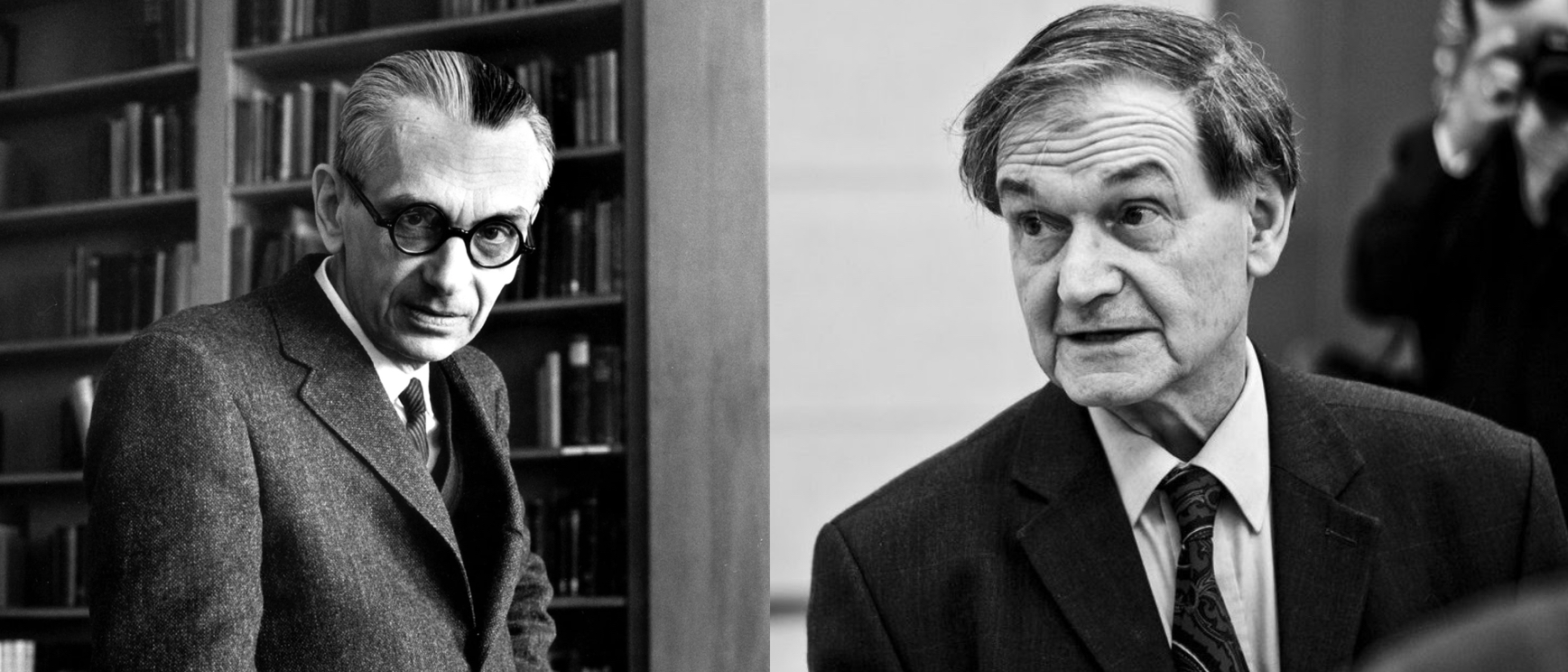

Can the Mind Be Reduced to a Machine: Gödel's Disjunction and the Penrose-Lucas Argument

09 Feb 2025This post was originally written in Korean, and has been machine translated into English. It may contain minor errors or unnatural expressions. Proofreading will be done in the near future.

This article is a summary of Peter Koellner, On the question of whether the mind can be mechanized (2018).

Abstract. The Church-Turing thesis and Gödel’s incompleteness theorems suggest the existence of mathematical truths that cannot be proved mechanically. However, if an ideal human mind can prove all mathematical truths, then the conclusion follows that the ideal human mind is not equivalent to a machine. This article examines the arguments of Lucas and Penrose, who attempt to establish anti-mechanism in such a manner, and introduces formal proofs that refute these arguments.

Introduction

The following are well-known results in logic:

-

Church-Turing Thesis. To be computable by an ideal machine is to be implementable by a Turing machine.

-

Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem. If $F$ is a formal system satisfying certain conditions, then there exists a sentence that is true but unprovable in $F$.

-

Formal System-Turing Machine Correspondence. If $F$ is a formal system satisfying certain conditions, then there exists a Turing machine that enumerates the propositions provable in $F$.

Combining these three theses with the fact that we humans appear to be capable of grasping mathematical truths not captured by formal systems—such as the consistency of arithmetic—the incompleteness theorem appears to suggest that the extension of mathematical results derivable by an ideal human mind exceeds the extension of results derivable by an ideal finite machine. That is, the incompleteness theorem appears to suggest anti-mechanism: that the mind cannot be reduced to a machine.

In this article, we examine how far this suggestion can be justified. As a result, we shall show that while the incompleteness theorem suggests anti-mechanism or Platonism, it does not directly suggest anti-mechanism.

1. Gödel’s Disjunction

Gödel argued that from the incompleteness theorem, it follows that at least one of the following two positions is true. We shall call this Gödel’s Disjunction.

-

Anti-mechanism: The mathematical results derivable by an ideal human mind always exceed the mathematical results derivable by an ideal finite machine. Therefore, the human mind cannot be reduced to a machine.

-

Platonism: There exist mathematical truths that cannot be grasped by an ideal human mind. Therefore, mathematical truth exists independently of the human mind.

It is noteworthy that both positions are contrary to materialist philosophy. while Gödel was generally reserved about philosophical arguments, he argued strongly that this particular argument was a “mathematically established fact”. Our first task is to verify whether this argument is indeed a “mathematically established fact”.

1.1. Gödel’s Three Claims

Let us introduce some notation.

-

$F$ is the set of all sentences that the formal system $F$ can prove.

-

$K$ is the set of all sentences that an ideal human mind can prove.

-

$T$ is the set of true sentences.

Throughout this article, we shall assume $K \subseteq T$. We also presuppose that $F$ is a formal system to which Gödel’s incompleteness theorem applies—that is, a consistent system containing Peano arithmetic (in fact, this condition can be weakened to Robinson arithmetic).

Before proceeding to the main discussion, let us review Gödel’s incompleteness theorem.

Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem. When $F$ is a consistent mathematical system containing arithmetic, the following holds:

- First Theorem. There exists a proposition that is true but unprovable in $F$.

- Second Theorem. The consistency of $F$ is an instance of the First Theorem.

Incidentally, while the incompleteness theorem traditionally targets Peano arithmetic, the incompleteness theorem also holds for weaker arithmetic systems, including Robinson arithmetic.

1.1.1. First Claim

Gödel first claims the following:

Claim 1. $F \subseteq T \implies F \subsetneq T$

The proof is as follows. If $F \subseteq T$, then $\mathrm{Con}(F) \in T$. However, by the Second Incompleteness Theorem, $\mathrm{Con}(F) \notin F$. Therefore, $F \subsetneq T$.

1.1.2. Second Claim

Gödel’s second claim is as follows:

Claim 2. $K(F \subseteq T) \implies F \subsetneq K$

The proof is as follows. If $K(F \subseteq T)$, then $\mathrm{Con}(F) \in K$. However, as we have seen, $F \subseteq T \implies \mathrm{Con}(F) \notin F$, so $F \subsetneq K$.

But if $F \subsetneq K$ is true, how should we understand this? One approach is to consider a hierarchy of formal systems.

Gödel emphasises that the unprovable sentences suggested by the incompleteness theorem need not be absolutely unprovable. This is because sentences unprovable in formal system $F$ may become provable in systems of higher order than $F$. For example, if $\mathsf{PA}$ is consistent, then while $\mathsf{PA}$ cannot prove $\mathrm{Con}(\mathsf{PA})$, it is known that second-order Peano arithmetic $\mathsf{PA}_2$ can prove $\mathrm{Con}(\mathsf{PA})$. Of course, $\mathsf{PA}_2$ cannot prove $\mathrm{Con}(\mathsf{PA}_2)$, but this is provable in third-order Peano arithmetic, and such a hierarchy continues.

This entire hierarchy appears to be subsumed under $K$. From this perspective, each formal system is like a set, and $K$ is like the collection of all sets. And just as the collection of all sets cannot be a set, an analogy holds that $K$ cannot be a formal system.

1.1.3. Third Claim

However, one might wonder: instead of writing “Claim 2” as a conditional, could we not claim $F \subsetneq K$ by asserting that $K(F \subsetneq T)$ is true?

Gödel points out that the incompleteness theorem alone cannot lead to such a claim. This is because the possibility of the existence of a formal system $F^*$ that coincides with $K$ cannot be completely ruled out (note that the previous discussion regarding higher-order Peano arithmetic was merely an analogy).

Regarding this, Gödel says:

[If such a formal system exists] human reason—at least in its mathematical aspect—is equivalent to a finite machine. However, that machine cannot completely understand its own operation [in the sense that it cannot prove its own consistency]. This inability would be mistaken by humans as the infinite extensibility of the mind.

Instead, Gödel’s third claim is as follows. This claim is Gödel’s disjunction.

Claim 3. $\forall F (F \subsetneq K) \; \lor \; K \subsetneq T$

The proof is as follows. Suppose there is a formal system $F^$ such that $F^ = K$. Since we have assumed $K \subset T$, we have $F^* \subset T$, and by Claim 1, $F^* \subsetneq T$.

The former signifies anti-mechanism, while the latter signifies Platonism.

1.2. Formalisation of Gödel’s Disjunction

So far, we have presented Gödel’s three claims and introduced brief proofs thereof. However, these proofs were not actually precise. This is because we did not introduce rigorous definitions of $F, K, T$, nor did we distinguish between what content can be proved within a formal system and what content can only be proved outside a formal system. To overcome this limitation, let us rigorously formalise $F, K, T$ and the proofs of Gödel’s three claims.

1.2.1. $F$

$F$ is the easiest concept to formalise. In particular, the following facts are known:

Formal System-Turing Machine Correspondence. When $F$ is a recursively axiomatisable formal system, there exists a Turing machine that recursively enumerates the propositions provable from $F$.

Additionally, the formal systems of interest to us are recursively axiomatisable.

Recursiveness of Kleene Predicates. The operation of Turing machines can be formalised within Peano arithmetic. Specifically, there exists a first-order logical predicate $K(x, y, z)$ that determines whether a Turing machine with Gödel number $x$, when given natural number $y$ as input, terminates with a computation record with Gödel number $z$.

As a corollary of the above two theorems, we obtain:

Corollary. Formal systems are recursively enumerable. That is, the “$e$-th formal system” $F_e$ can be defined in Peano arithmetic.

For example, $F_{123}$ might be Robinson arithmetic, $F_{456}$ might be ZFC, and so forth. $F_{123}(\ulcorner 1 + 1 = 2 \urcorner)$ means that $1 + 1 = 2$ is provable in Robinson arithmetic. And $\mathsf{PA} \vdash F_{123}(\ulcorner 1 + 1 = 2 \urcorner)$.

1.2.2. $T$

The most promising formal definition of $T$ is Tarski’s typed truth definition. while Tarski’s typed truth definition is a syntactic rather than semantic definition, it is suitable for the purposes of the present discussion. Tarski’s definition consists of axioms including the following:

-

$\forall x : \mathrm{Sent}(x) \rightarrow (T(\hat{\lnot} x) \leftrightarrow \lnot T(x))$

-

$\forall x, y : [\mathrm{Sent}(x) \land \mathrm{Sent}(y)] \rightarrow [T(x\; \hat{\lor} \;y) \leftrightarrow T(x) \lor T(y)]$

Here, $\mathrm{Sent}$ determines whether a given sentence (or its Gödel number) is well-formed. Meanwhile, $\hat{\quad}$ is introduced to distinguish between language and meta-language; a detailed explanation is not particularly important, so we shall leave it at this.

1.2.3. $K$

$K$ is the most challenging of the three concepts. Not only can we not provide a complete semantic definition, but there are also questionable aspects to providing a syntactic definition. However, since the goal of this article is to demonstrate that $F \subsetneq K$ cannot be directly shown from the incompleteness theorem, according to the principle of charity, we shall present the following syntactic definition that maximally guarantees the extension of $K$.

Syntactic Definition of $K$.

- When $\phi$ is logically true, $K\phi$.

- For arbitrary sentences $\phi, \psi$: $(K(\phi \rightarrow \psi) \land K\phi) \rightarrow K\psi$.

- For arbitrary sentence $\phi$: $K\phi \rightarrow \phi$.

- For arbitrary sentence $\phi$: $K\phi \rightarrow KK\phi$.

Here, $K$ is a logical operator. Therefore, we write $K\phi$ rather than $K(\phi)$ or $K(\ulcorner \phi \urcorner)$. For the reason why $K$ should be regarded as a logical operator rather than a predicate, see footnote 29 of the original paper.

1.2.4. $\mathsf{EA}$ and $\mathsf{EA}_T$

Let us construct a formal system capable of reasoning about $F, K, T$. Firstly, as we saw in 1.2.1, $F$ is already formalisable in $\mathsf{PA}$, so no special measures are required.

Let $L_{\mathsf{EA}}$ be defined as $\mathsf{PA}$ with the function $K$ added. Let $\Sigma$ be the collection of axioms of $\mathsf{PA}$ and the axioms of the syntactic definition of $K$ (where the induction schema of $\mathsf{PA}$ is taken over sentences of $L_{\mathsf{EA}}$ rather than $L_{\mathsf{PA}}$). The axioms of $\mathsf{EA}$ are $\Sigma \cup K\Sigma$.

Let $L_{\mathsf{EA}T}$ be defined as $\mathsf{EA}$ with the predicate $T$ added. Let $\Sigma^*$ be the collection of $\Sigma$ and the axioms of the syntactic definition of $T$ (where the induction schema of $\mathsf{PA}$ is taken over sentences of $L{\mathsf{EA}_T}$). The axioms of $\mathsf{EA}_T$ are $\Sigma^* \cup K\Sigma^*$.

1.3. Formal Proof of Gödel’s Disjunction

We show that Gödel’s three claims are formally provable in $\mathsf{EA}_T$.

1.3.1. First Claim

Claim 1. $F \subseteq T \implies F \subsetneq T$

This claim is easily provable in $\mathsf{EA}_T$. This is because it is a direct consequence of Gödel’s incompleteness theorem.

1.3.2. Second Claim

Claim 2. $K(F \subseteq T) \implies F \subsetneq K$

This claim is also provable in $\mathsf{EA}_T$. In fact, the following stronger result is provable:

Reinhardt’s First Theorem. For arbitrary sentence $\phi$, if

\[\mathsf{EA} \vdash K(F(\ulcorner \phi \urcorner) \rightarrow \phi)\]then there exists some sentence $\psi$ such that

\[\mathsf{EA} \vdash K\psi \land K\lnot F(\ulcorner \psi \urcorner)\](that is, $\mathsf{EA} \vdash F \subsetneq K$).

1.3.3. Third Claim

Claim 3. $\forall F (F \subsetneq K) \; \lor \; K \subsetneq T$

Expanding $F \subsetneq K$ in the above claim gives:

\[\forall e \; \exists x \;(\mathrm{Sent}_{L_{\mathsf{PA}}}(x) \land K(x) \land x \notin F_e )\]And expanding $K \subsetneq T$ gives:

\[\exists x \;(\mathrm{Sent}_{L_{\mathsf{PA}}}(x) \land T(x) \land \lnot K(x) \land \lnot K(\lnot x))\]However, there is a problem here. As mentioned earlier, since $K$ is a logical operator rather than a predicate, it cannot be placed within a quantified context. Just as $\exists \phi : \lnot\phi$ is not grammatically correct. To circumvent this problem, instead of writing $\exists x \; K(x)$, we write $\exists x\; T(\hat{K}x)$. Therefore, the correct formalisation of Claim 3 is as follows:

\[\begin{gather} \forall e \; \exists x \;(\mathrm{Sent}_{L_{\mathsf{PA}}}(x) \land T(\hat{K}x) \land x \notin F_e ) \\\\ \lor\\\\ \exists x \;(\mathrm{Sent}_{L_{\mathsf{PA}}}(x) \land T(x) \land \lnot T(\hat{K}x) \land \lnot T(\hat{K}\lnot x)) \end{gather}\]Let us call the above formula $\mathrm{GD}$. The following theorem is known:

Reinhardt’s Second Theorem. $\mathsf{EA}_T \vdash \mathrm{GD}$.

Therefore, Gödel’s disjunction is provable under an appropriate formal system.

2. Lucas and Penrose

2.1. The Consistency Decision Problem

Lucas and Penrose attempt to directly show $F \subsetneq K$ by claiming $K(F \subseteq T)$. That is, Lucas and Penrose argue that the ideal human mind has the ability to determine whether any given formal system is consistent or not, and accordingly claim $\forall F \subseteq T: F \subsetneq K$.

However, it is highly questionable whether the ideal human mind has the ability to determine the consistency of arbitrary formal systems. For instance, let $R$ be the Riemann hypothesis. $R$ can be formalised as a $\Pi_1$ proposition in Peano arithmetic. And as mentioned earlier, since $\mathsf{PA}$ is $\Sigma_1$-complete, the consistency of $\mathsf{PA} + R$ is equivalent to $R$. This example shows that there are cases where the consistency decision problem for formal systems is at least as difficult as the Riemann hypothesis.

2.2. Relative Consistency of Mechanism

This fact alone would put Lucas and Penrose’s project in difficulty, but we can go further and show a more powerful fact. That fact is that $K(F\subseteq T)$ is formally unprovable. This is because mechanistic theses are consistent with $\mathsf{EA}_T$.

Before showing this, it is useful to classify mechanistic theses according to their strength. Reinhardt’s classification adopted in this article is as follows:

- Weak Mechanical Thesis (WMT): $\exists e \; ( K = F_e )$

- Strong Mechanical Thesis (SMT): $K\exists e\; (K = F_e)$

- Super Strong Mechanical Thesis (SSMT): $\exists e \; K(K = F_e)$

To explain each:

- WMT: The ideal human mind is equivalent to some Turing machine.

- SMT: The ideal human mind knows that it is equivalent to some Turing machine.

- SSMT: The ideal human mind knows that it is equivalent to a specific Turing machine.

The following is known:

Reinhardt’s Third Theorem. $\mathsf{EA}_T + \mathsf{SSMT}$ is inconsistent.

Therefore, assuming the axioms of $\mathsf{EA}T$, the super strong mechanical thesis is false. In short, even if a computer equivalent to the ideal human mind were given, we could not know whether it is _truly equivalent to the human mind.

However, this fact alone is insufficient to support Lucas and Penrose. This is because the core thesis of mechanism is not the method of identifying machines with capabilities equivalent to ours, but the existence of machines with capabilities equivalent to ours. Regarding this, the following is known:

Reinhardt’s Fourth Theorem. $\mathsf{EA}_T + \mathsf{WMT}$ is consistent.

Furthermore, the following is known:

Carlson’s Theorem. $\mathsf{EA}_T + \mathsf{SMT}$ is consistent.

That is, $\mathsf{EA}_T$ not only leaves open the possibility of the existence of a machine equivalent to the ideal human mind, but also leaves open the possibility that the human mind can prove this fact itself. These facts show that attempts to establish anti-mechanism solely through the incompleteness theorem are bound to fail.

2.3. Gödel’s Insight

Remarkably, Gödel appears to have understood all of this discussion from the beginning. According to Wang’s recollections of conversations with Gödel:

The incompleteness theorem does not rule out the possibility of a computer that produces results equivalent to human mathematical intuition [$\exists e\; (F_e = K)$]. However, it does suggest the following: if that possibility—though the probability is extremely low due to other considerations—is true, then either we cannot know the design of such a computer [$\lnot K (F_e = K)$], or we cannot know that the computer operates correctly [$\lnot K (F_e \subseteq T)$].

3. Conclusion

The discussion thus far should be sufficient to prevent further attempts to directly derive anti-mechanism from Gödel’s disjunction. However, there is another approach to arguing for anti-mechanism from logical results. This argument, commonly called Penrose’s new argument, is an argument that puts forward type-free truth, as distinguished from Tarski’s typed truth. The formalisation of this argument and its implications will be addressed in Part 2 of this paper.