An Intuitive Understanding of Adjoints

16 Dec 2024One of the central concepts in category theory is that of an adjoint.

Definition. Let $\mathcal{A}, \mathcal{B}$ be categories, and let $F: \mathcal{A} \to \mathcal{B}, G: \mathcal{B} \to \mathcal{A}$ be functors. We say that $F$ is a left adjoint to $G$, written as $F \dashv G$, if for any $A \in \mathcal{A}, B \in \mathcal{B}$, there exists a natural correspondence between $\hom_\mathcal{B}(F(A), B)$ and $\hom_\mathcal{A}(A, G(B))$. That is,

\[\begin{gather} (F(A) \xrightarrow{g} B) \quad \mapsto \quad (A \xrightarrow{\bar{g}} G(B))\\ (A \xrightarrow{f} G(B)) \quad \mapsto \quad (F(A) \xrightarrow{\bar{f}} B) \end{gather}\]We also call $G$ the right adjoint to $F$.

This may feel very abstract, but there is a couple of examples that could be of assist in grasping the definition.

1. Adjoints as Approximations

When $F \dashv G$, the functors $F$ and $G$ can be thought of as approximating objects in $\mathcal{A}$ and $\mathcal{B}$ with respect to each other. In particular, the left adjoint represents approximation ‘from left to right’, while the right adjoint represents approximation ‘from right to left’.

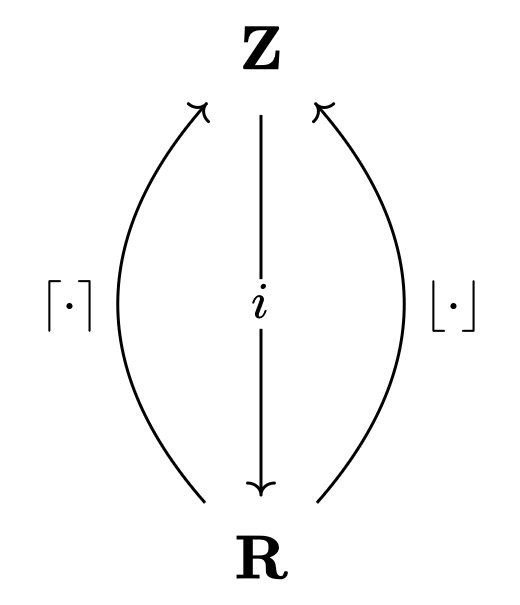

For example, let $\mathbf{Z}$ be a category whose objects are integers, with a unique morphism $x \to y$ existing if and only if $x \leq y$. Similarly, let $\mathbf{R}$ be a category whose objects are real numbers, with a unique morphism $x \to y$ existing if and only if $x \leq y$. We may think of $\lceil \cdot \rceil, \lfloor \cdot \rfloor$ as functors $\mathbf{R} → \mathbf{Z}$, and the inclusion map $\iota$ as a functor $\mathbf{Z} → \mathbf{R}$. It then follows that $\lceil \cdot \rceil \dashv \iota \dashv \lfloor \cdot \rfloor$.

That is, $\lceil \cdot \rceil$ is a transformation that ‘lifts [a number] from left to right’ by mapping $r$ to $\lceil r \rceil$ with $r \leq \lceil r \rceil$, while $\lfloor \cdot \rfloor$ is a transformation that ‘pulls [a number] from right to left’ by mapping $r$ to $\lfloor r \rfloor$ with $\lfloor r \rfloor \leq r$.

Furthermore, let $I$ and $T$ be the initial object and terminal object of $\mathcal{A}$ respectively. That is, for any $A \in \mathcal{A}$:

- There exists a unique morphism $I \to A$.

- There exists a unique morphism $A \to T$.

For instance, in $\mathbf{Set}$, the empty set is the initial object and any singleton set is a terminal object.

For the singleton category $\mathcal{S}$, there exists a unique functor $F: \mathcal{A} \to \mathcal{S}$ that maps every object of $\mathcal{A}$ to the single object of $\mathcal{S}$. Let $G_I, G_T: \mathcal{S} \to \mathcal{A}$ be functors that maps the single object of $\mathcal{S}$ to $I$ and $T$, respectively. It then follows that $G_T \dashv F \dashv G_I$. (Since the terminal object is the ‘rightmost’ object, $G_T$ represents approximation ‘from left to right’, while since the initial object is the ‘leftmost’ object, $G_I$ represents approximation ‘from right to left’.)

2. Adjoints as Construction and Destruction

Left adjoints are associated with construction, while right adjoints are associated with destruction. Therefore, free functors are generally left adjoints, while forgetful functors are right adjoints.

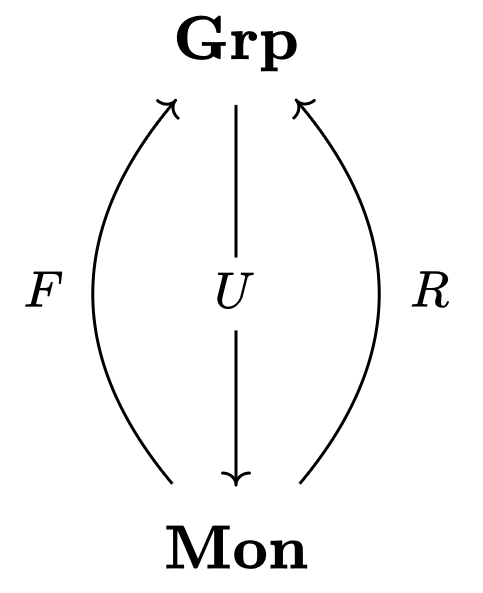

For instance, let $\mathbf{Grp}$ be the category of groups and $\mathbf{Mon}$ be the category of monoids. Let $F$ be the free functor and $U$ be the forgetful functor. Define $R: \mathbf{Mon} → \mathbf{Grp}$ as follows:

- $R(M) = \lbrace m \in M : \exists m^{-1} \in M \rbrace$

- $R(f): m \mapsto f(m)$

Then the following diagram holds, yielding $F \dashv U \dashv R$.

One can understand $U \dashv R$ as expressing that $R$ is more destructive than $U$.