Bell's Spaceship Paradox: Passive and Active Lorentz Contraction

17 Nov 2024Spaceships A and B are connected by a thin thread and are initially at rest (with respect to a common inertial frame). They begin to accelerate simultaneously at the same rate to approach the speed of light. What happens to the thread?

- It breaks.

- It loosens.

- It remains unchanged.

This thought experiment was originally devised by Dewan and Beran in 1959 but gained widespread attention after John Stewart Bell discussed it with CERN physicists in 1976. Bell argued that the thread breaks due to Lorentz contraction. Most CERN physicists disagreed, claiming the thread remains unchanged. One prominent physicist even accused Bell of misrepresenting relativity. So, who is correct?

The answer is 1. It breaks.

This may seem counterintuitive. After all, Lorentz contraction is frame-dependent. If Alice moves at near-light speed relative to Bob, Bob would observe Alice to have contracted. But in Alice’s frame, it is Bob who is moving and therefore contracts. This symmetry suggests that Lorentz contraction is a mathematical artifact arising from frame choice, hence not a physically real phenomenon. Such an interpretation is widespread in physics, e.g. Rindler’s 1977 writes:

According to Lorentz, the cause of contraction lies in the increased electromagnetic cohesion of atomic structures [as an object passes through the ether]… [But] in relativity, Lorentz contraction is essentially a geometric projection effect, akin to viewing a stationary rod from an angle.1

However, Rindler’s explanation is quite misleading. Rather, it is important to recognise that there are two types of Lorentz contraction. In the case of a passive Lorentz transformation, Lorentz contraction is merely an artifact of changing coordinates. But in the case of an active Lorentz transformation, the contraction corresponds to a real physical effect, such as increased electromagnetic force. This post will explore the difference between the two and show how active transformation relates to physical stress.

1. Passive Transformation

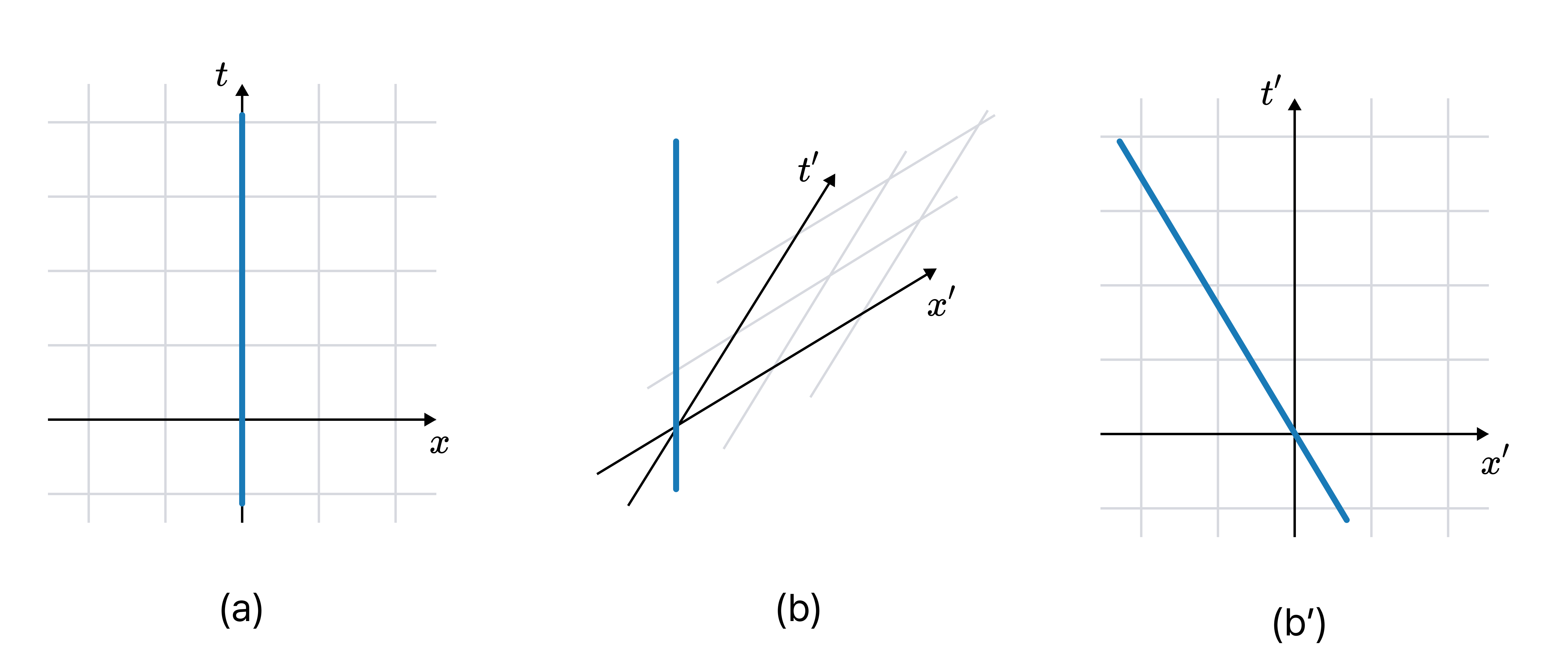

Consider a point particle A moving inertially in vacuum. The Minkowski diagram, with respect to an inertial coordinates $(x, t)$ to which A is at rest, is shown in (a). In another inertial coordinates $(x’, t’)$ moving at $0.6c$ relative to $(x, t)$, the Minkowski diagram is as shown in (b) and (b’).2

The diagrams (a) and (b) represent the same physical scenario using different coordinates. Such transformation between coordinates is called a passive transformation. In Newtonian mechanics, this is represented as shear transformation of Galilean diagram; in relativity, as Lorentz transformation of Minkowski diagram.

2. Active Transformation

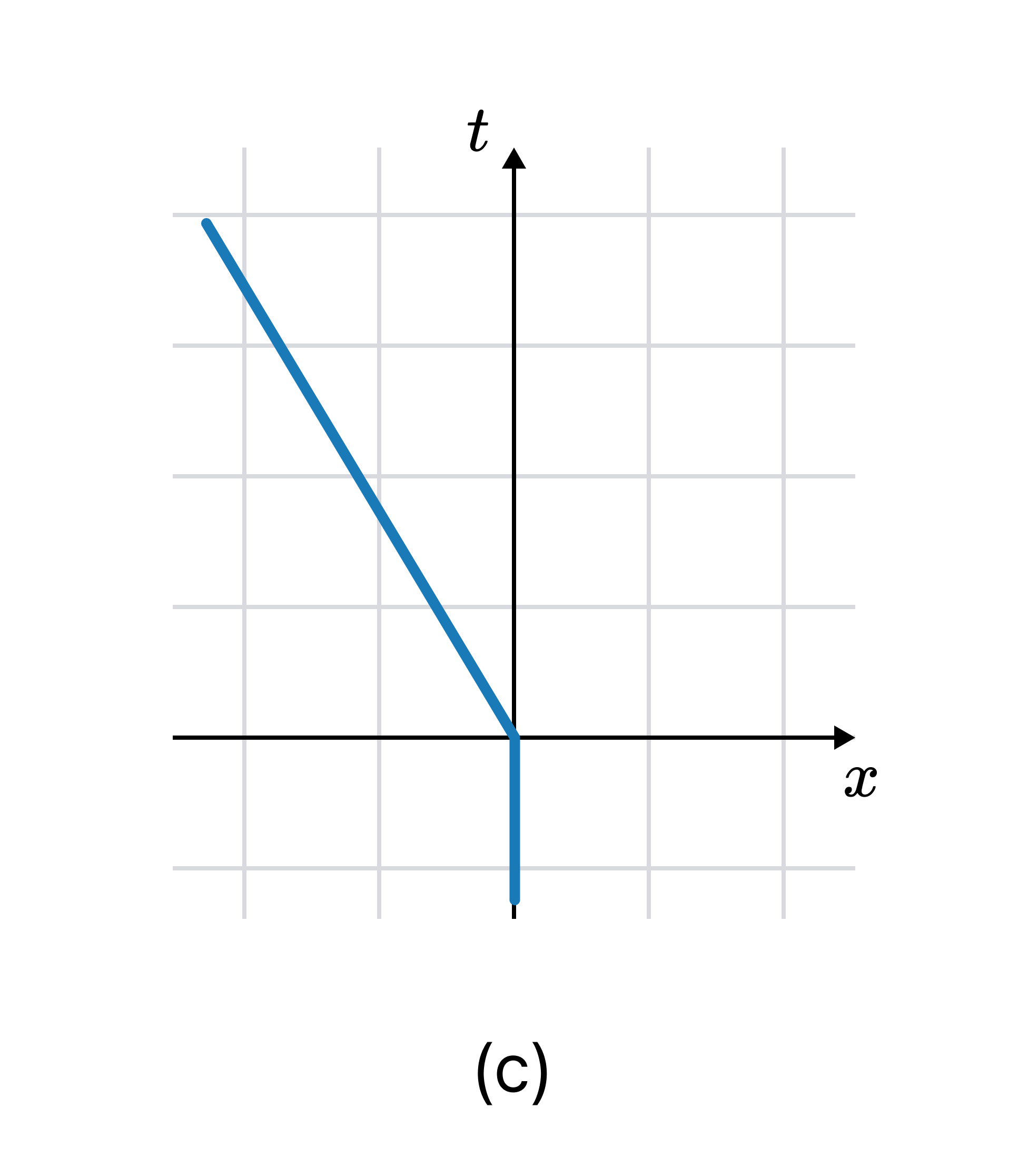

Now consider a scenario where A’s velocity changes by $-0.6c$. The Minkowski diagram in $(x, t)$ after this change is shown in (c).

Unlike (a) and (b’), diagrams (a) and (c) use the same coordinates. The change here reflects a physical change in A’s motion, not a change in coordinates. Such a transformation is called an active transformation.

At first glance, the difference between active and passive transformations might seem purely semantic. In classical mechanics, the two are indeed physically equivalent, and this is partly what grounds Noether’s theorem. But in relativity, the distinction becomes crucial due to the relativity of simultaneity.

3. Relativity of Simultaneity

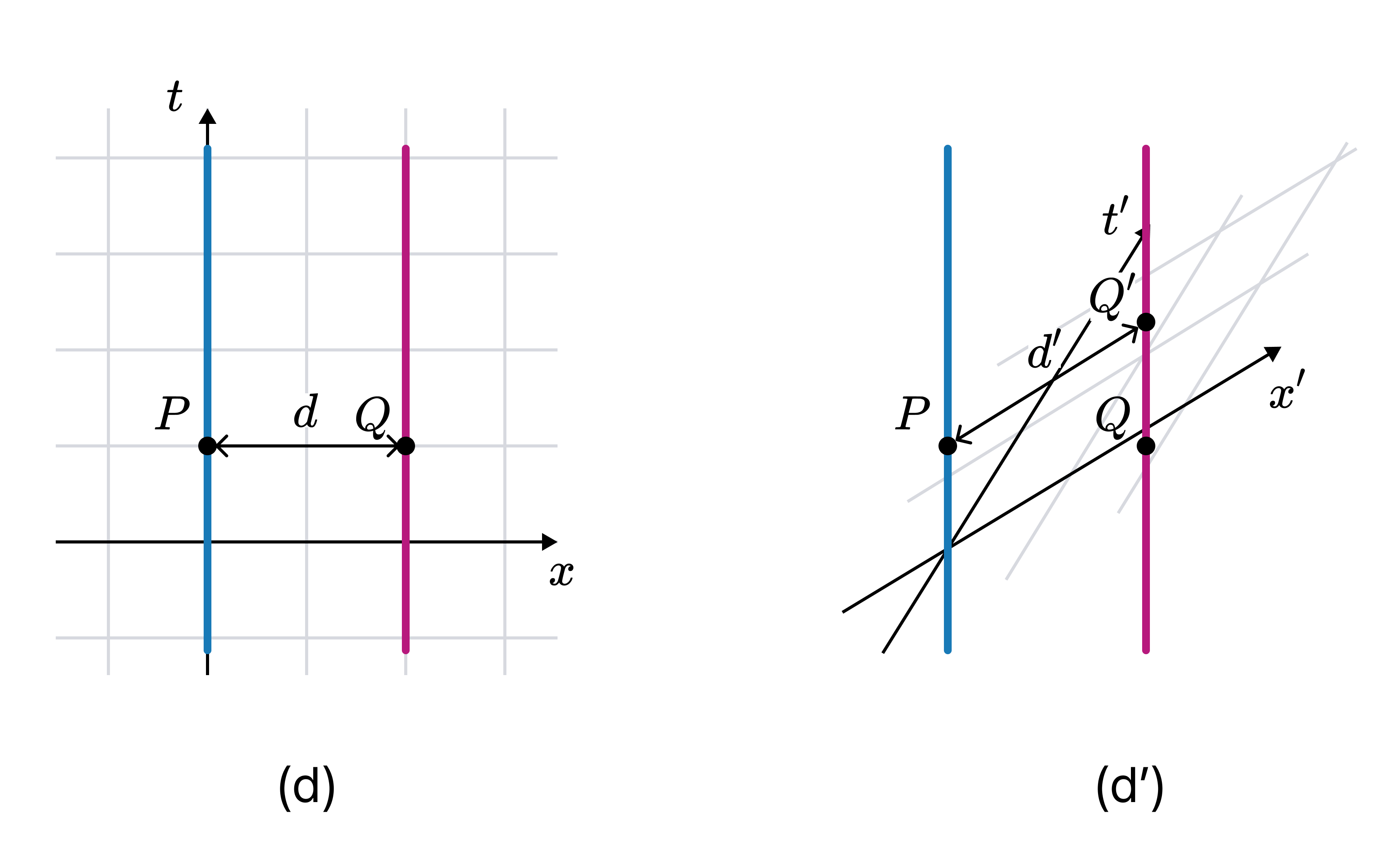

To understand why simultaneity matters, let’s consider two particles A and B maintaining a distance $d$ apart. The Minkowski diagrams based on A’s rest coordinates $(x, t)$ and another diagram based on coordinates $(x’, t’)$ moving at $0.6c$ are shown below:

In $(x, t)$, events $P$ and $Q$ are simultaneous, so the distance between A and B is $d$. But in $(x’, t’)$, $P$ and $Q’$ are simultaneous, and the distance is $d’$. To calculate $d’$ we use the Lorentz transformation formulas:

\[\begin{align} &t' = \gamma \left( t - \frac{vx}{c^2} \right)\\ &x' = \gamma (x - vt)\\ &y' = y\\ &z' = z\\ \end{align}\]Calculation gives $d’ = 0.8d$, i.e. $d’ < d$.3

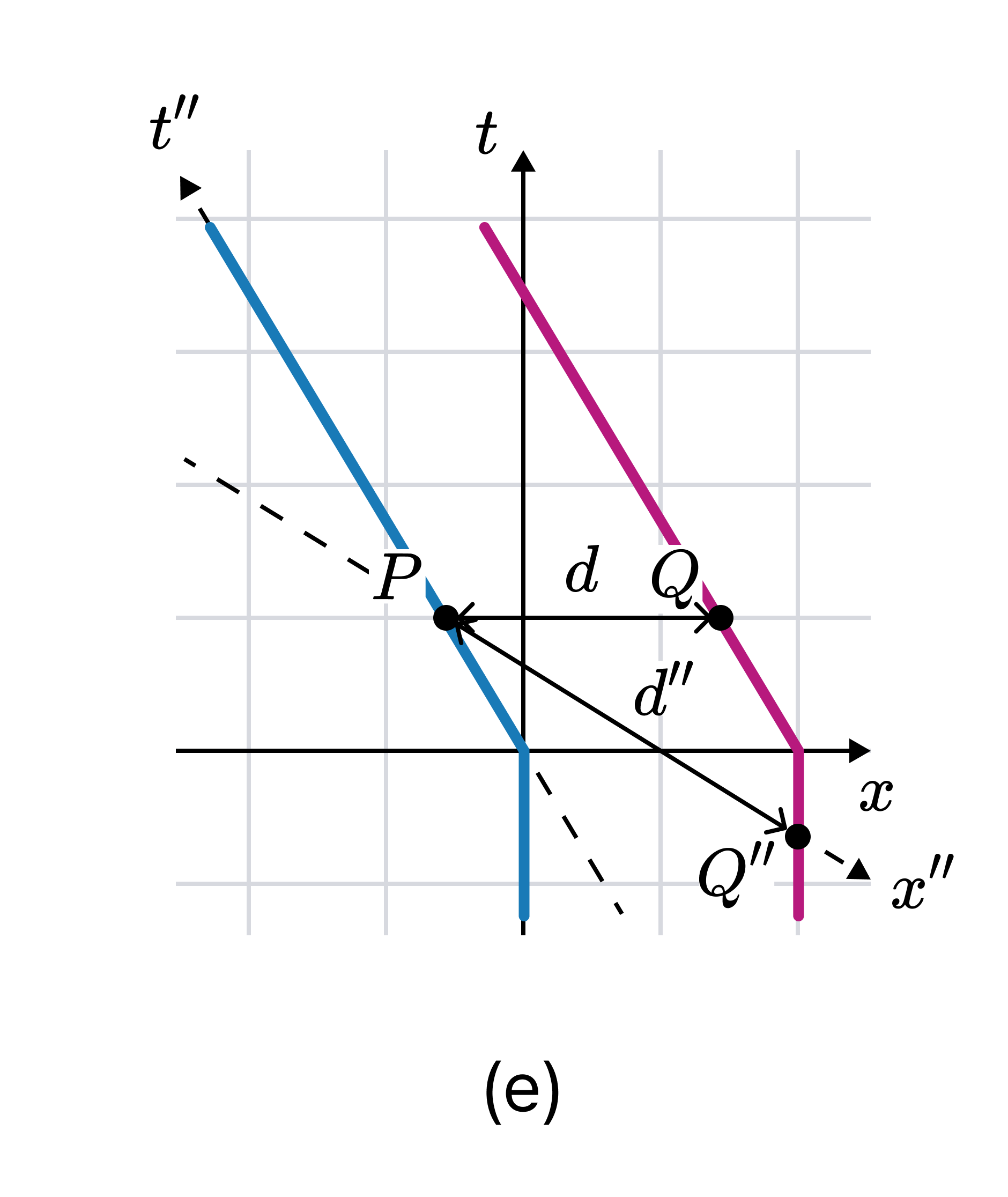

Now let’s consider the active transformation case. Suppose A and B, initially at distance $d$, are both accelerated simultaneously, with respect to $(x, t)$, to $-0.6c$. The resulting Minkowski diagram is:

In $(x, t)$, $P$ and $Q$ are simultaneous, and their distance remains $d$. But in $(x'', t'')$, the coordinates to which A is at rest after the acceleration, $P$ and $Q''$ are simultaneous, and the distance is $d'' = 1.25d$. Hence $d'' > d$.

Thus, in relativity, passive and active transformations lead to physically different consequences. Passive transformations preserve distances in A’s frame but contract them in the moving frame, whereas active transformations preserve distances in the original frame but stretch them in A’s new frame.

| Distance between A and B | Rest Frame of A | Moving Frame of A |

|---|---|---|

| Passive Transformation | Unchanged | Contracted |

| Active Transformation (isolated) | Expanded | Unchanged |

4. Active Transformation of a Rigid Body

Up to now, A and B were isolated particles. Now suppose A and B are endpoints of a rigid rod M of length $l$.

Suppose that every part of M accelerates simultaneously with respect to an inertial frame $(x, t)$ to reach $0.6c$. If M were not rigid, A would observe M’s length as expanding to $1.25c$. But rigidity resists this expansion, leading to an internal stress. Thus from A’s frame of reference, the rod undergoes two two effects.

- Effect 1: Due to relativity of simultaneity, B accelerates before A, which would cause the rod to stretch.

- Effect 2: The rod’s rigidity resists this stretching, generating internal stress.

The internal stress thus arisen is called relativistic stress. If M is strong enough, it endures the stress and maintains its original length. Otherwise, it deforms or breaks. For example, a biscuit rapidly accelerated to near-light speed would shatter, while a rugby ball accelerated to near-light speed would visibly extend.

5. Conclusion

| Distance between A and B | Rest Frame of A | Moving Frame of A |

|---|---|---|

| Passive Transformation | Unchanged | Contracted |

| Active Transformation (isolated) | Expanded | Unchanged |

| Active Transformation (rigid body) | Unchanged | Contracted |

Returning to Bell’s paradox, when spaceships A and B accelerate, the “spaceship-thread-spaceship” system undergoes an active transformation. Thus in A’s frame, two effects co-occur:

- Effect 1: Distance between A and B increases (since they are not rigidly connected).

- Effect 2: The thread tries to maintain its original length.

Eventually, if acceleration continues, Effect 1 wins over Effect 2, and the thread breaks. If A and B were connected by a steel cable instead, Effect 2 would dominate, and the distance would remain constant.

-

Rindler (1977), p. 41. Quoted in Maudlin, Philosophy of Physics: Space and Time. ↩

-

Diagrams (a) and (b) correspond to the same physical situation but with different coordinates, akin to rendering the same cube using different projections (e.g. orthographic v. isometric). Diagrams (b) and (b’) are the same diagram represented differently, akin to drawing the same cube using the same projection from different perspective. ↩

-

Though it appears to be $d’ > d$ in the diagram, recall that Minkowski geometry uses non-Euclidean distance. Just as Alaska may appear as large as Africa on a flat map, but isn’t, Minkowski diagrams visually misrepresent distances. ↩